More than 50 countries go to the polls in 2024. The year will test even the most robust democracies

- Share via

LONDON — More than 50 countries that are home to half the planet’s population are due to hold national elections in 2024, but the number of citizens exercising the right to vote is notunalloyed good news. The year could test even the most robust democracies and strengthen the hands of leaders with authoritarian leanings.

In places as varied as Russia, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, India, El Salvador and South Africa, elections for leaders and national legislatures will have huge implications for human rights, economies, international relations and prospects for peace in a volatile world.

In some countries, the balloting will be neither free nor fair. And for many, weary electorates, curbs on opposition candidates, and the potential for manipulation and disinformation have made the fate of democracy a front-and-center campaign issue.

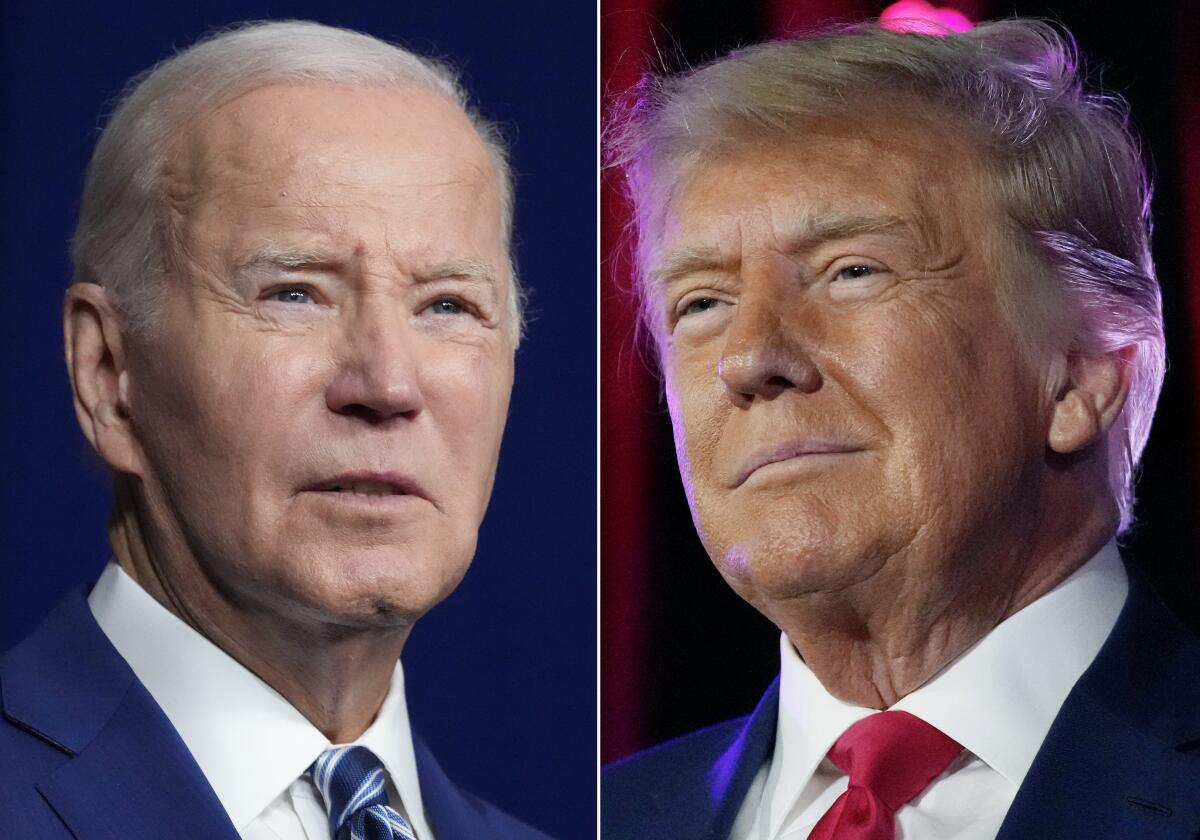

A possible rematch between President Biden and his predecessor, Donald Trump, looms large on the election calendar. A potential Trump victory in November is perhaps the greatest global wild card.

Yet high-stakes votes before then also will gauge the “mood of dissatisfaction, impatience, uneasiness” among far-flung electorates, said Bronwen Maddox, director of the London-based think tank Chatham House.

Disinformation is exacerbating political polarization and mistrust amid a tight presidential race in Taiwan, where tension with China is running high.

VOTES WITH GLOBAL IMPACT

Taiwan’s election for president and the 113-member Legislature takes place Saturday amid intense pressure from China, making the outcome important to much of the Asia-Pacific region as well as to the U.S.

Beijing has renewed its threat to use military force to annex the self-governing island it regards as its own territory, and has described the election as a choice between war and peace. None of the three leading presidential candidates has indicated a desire to try China’s resolve by declaring Taiwan’s independence.

That said, front-runner William Lai, who is currently Taiwan’s vice president, has promised to strengthen the island’s defense, and a victory by him could heighten cross-strait tensions. The opposition Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang, is more amenable to Beijing than Lai’s Democratic Progressive Party.

Taiwan’s 23 million people overwhelmingly favor maintaining the island’s de facto independence through self-rule. Domestic issues such as housing and healthcare therefore are likely to play a deciding role in the presidential race.

Vladimir Putin aims to prolong his repressive grip on Russia for at least six more years through a presidential election he is all but certain to win.

LEADERS LOOK TO TIGHTEN THEIR GRIPS

Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the world’s longest-serving female leader, won a fourth successive term on Monday in an election that opposition parties boycotted and that was preceded byviolence. Hasina’s Awami League party was reelected on a low turnout of 40%, and the stifling of dissent risks triggering more turmoil.

India, the world’s most populous country, is due to hold a general election by midyear that could bring Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party a third consecutive term.

To his supporters, Modi is a political outsider who has cleaned up government after decades of corruption and made India an emerging global power. But critics say assaults on the news media and free speech, as well as attacks on religious minorities by Hindu nationalists, have grown brazen on his watch.

Another leader seeking to retain power is El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele, who has won widespread support since he used emergency powers for an aggressive crackdown on violent street gangs.

On Feb. 4, a Salvadoran Supreme Court filled by his party’s appointees cleared Bukele to run despite a constitutional ban on presidents serving consecutive terms. Foreign governments have criticized the suspension of some civil rights in El Salvador, but Bukele is not expected to face serious competition.

El Salvador’s President Bukele registers for 2024 reelection — which the constitution does not allow

El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele has registered to run for reelection, which is prohibited by the constitution -- though the Supreme Court says a provision allows it.

MILESTONES — AND MORE OF THE SAME

Mexico is poised to elect its first female president on June 2 — either former Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, a protege of current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador; or a former opposition senator, Xóchitl Gálvez. The winner will govern a country with daunting drug-related violence and an increasingly influential military.

Voters in Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest democracy, will choose a successor to President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, on Feb. 14.

Polls indicate a close race between Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto, a right-wing nationalist, and former Central Java Gov. Ganjar Pranowo, the governing party’s candidate.

Subianto’s running mate is the son of Jokowi, which has prompted speculation of a dynasty in the making. But either winner would mark a continuation of the corruption-tainted politics that have dominated Indonesia since the end of the Suharto dictatorship in 1998.

Pakistan’s Feb. 8 parliamentary election also is being contested by established politicians, under the eye of the country’s powerful military. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan, a popular opposition figure, is imprisoned, and election officials blocked him from running.

Three-time Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, leader of the Muslim League, was allowed on the ballot after his corruption convictions were overturned. Also running is the People’s Party leader, former Foreign Minister Bulawal Bhutto Zardari.

Analysts say the election is likely to produce a shaky government. The vote may be postponed amid plummeting relations with Taliban-controlled neighbor Afghanistan and deadly attacks on Pakistani security forces.

With the ruling party nomination, López Obrador protege Claudia Sheinbaum is favored to be Mexico’s next president; she’s facing Sen. Xóchitl Gálvez.

HAS POPULISM PEAKED?

Populism gained ground in Europe as the continent experienced economic instability and mass migration from elsewhere. June elections for the Parliament of the 27-nation European Union will be a sign of whether traditional parties can see off populist rivals, many of which are skeptical of giving military support to Ukraine.

National elections last year produced mixed signals: Slovakia elected pro-Russia populist Prime Minister Robert Fico, but voters in Poland replaced a conservative government with a coalition led by centrist Donald Tusk.

Mujtaba Rahman of the Eurasia Group political consultancy predicted that this year’s European Parliament races wouldn’t produce a populist majority, but that “the center will lose ground compared to the last vote,” in 2019.

In former EU member Britain, populism found expression in the 2016 Brexit referendum and the turbulent term of former Prime Minister Boris Johnson. A general election this year will pit the U.K.’s governing Conservatives against the center-left Labor Party, which is firmly ahead in opinion polls as it seeks to regain power after 14 years.

A Pakistani court acquits former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in a graft case, removing a major obstacle for him to run in parliamentary elections.

DEMOCRACY’S CHALLENGES IN AFRICA

Climate change, disrupted grain supplies due to the Russia-Ukraine war, and increasing attention from China and Russia are among the forces reshaping Africa, the world’s fastest-growing continent.

Eight West African countries have experienced military coups since 2020, including Niger and Gabon in 2023.

Senegal is regarded as a bastion of stability in the region. Now that President Macky Sall is stepping down, his country’s Feb. 25 election is seen as an indicator of the country’s political resilience.

Supporters of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko accuse the government of trying to stop him from running with a series of legal cases that have sparked deadly protests. The election could “mark a return to the norms of previous years or signal a lasting shift towards more volatile politics,” said Eurasia group analyst Tochi Eni-Kalu.

The list of security challenges keeps growing for election officials preparing for the 2024 presidential election.

In South Africa, a legislative election is due between May and August, with a struggling economy, crippling power blackouts and an unemployment rate of nearly 32% as the political backdrop. Overcoming voter disillusionment will be a challenge for the long-dominant African National Congress.

The ANC has held the presidency and a majority in parliament since the end of the country’s racist apartheid system in 1994, but the once-revered party won less than half of the vote in local elections in 2021.

If its support drops below 50%, the party will need to form a coalition to ensure that lawmakers reelect President Cyril Ramaphosa.

South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, plans to hold its long-delayed first election in December. The balloting would represent a key milestone, but could be rife with danger and vulnerable to failure under current conditions.

Nicholas Haysom, who heads the United Nations mission in the country, told the U.N. Security Council last month that voter registration details, a security plan and a method for resolving electoral disputes are among the elements still lacking to ensure a free election that is “deemed credible and acceptable to South Sudanese citizens.”

RUBBER-STAMP EXERCISES

There’s little doubt about who will win Russia’s presidential election in March. President Vladimir Putin faces only token opposition in his bid for a fifth term. His main rivals are in prison, in exile, dead or disqualified.

It’s a similar story in Belarus, led by President Alexander Lukashenko. On Feb. 25, the country is expected to hold its first parliamentary election since Lukashenko’s government crushed protests against the Putin ally’s disputed 2020 reelection. Thousands of opponents are in prison or have fled the country.

Still, Maddox said that for all its problems, the democratic ideal retains widespread appeal, even for authoritarian leaders.

“The fact that they choose to hold elections shows that they see the value of claiming to have a free vote,” she said.

Associated Press writers around the world contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.