Why Venezuela wants to seize a big chunk of its smaller neighbor

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — Concerns that an armed conflict may be imminent in the northern hinterlands of South America eased somewhat Thursday as the leaders of Venezuela and neighboring Guyana pledged to find a peaceful solution to a territorial dispute that has been simmering for centuries but has recently heated up anew.

The prospect of a military confrontation emerged in recent weeks as Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has threatened to annex a vast resource-rich swath of Guyana, alarming the United Nations, the United States, Brazil and other nations.

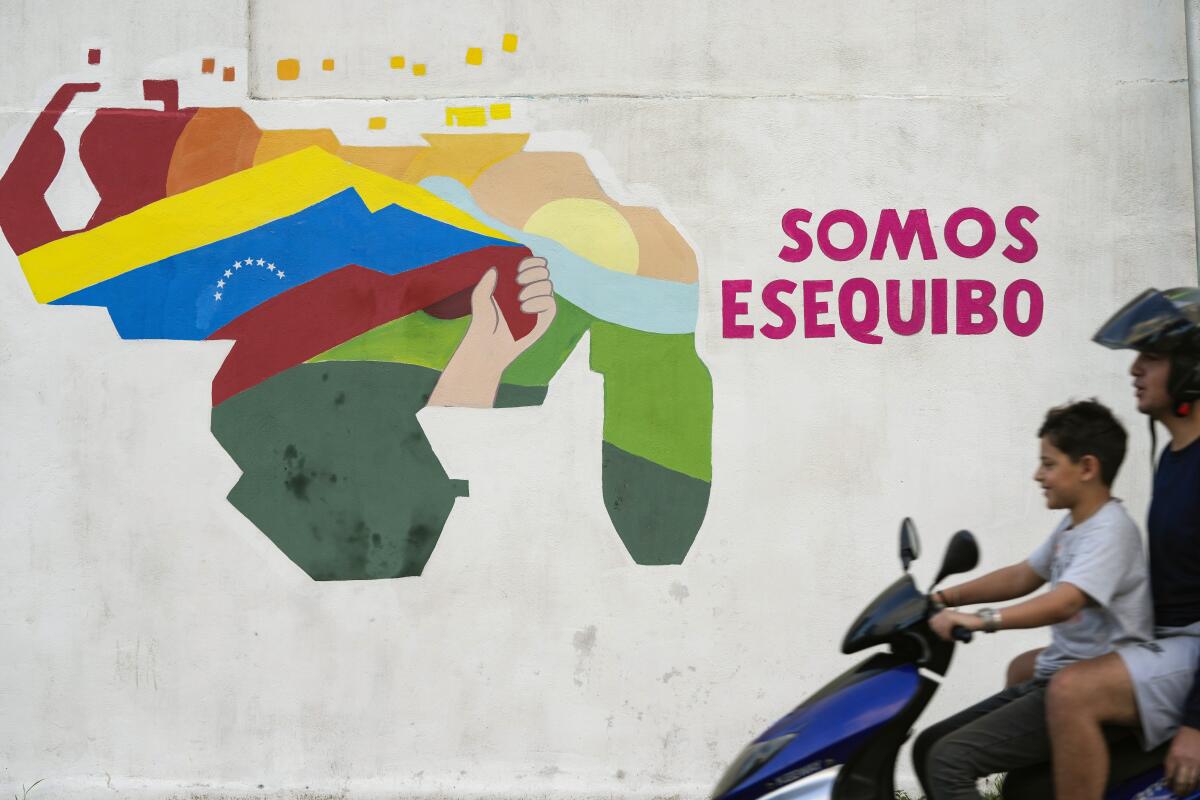

Maduro’s claims on the region — which Venezuelans call Guayana Esequiba and Guyanese call Essequibo — come as he faces unpopularity at home and growing international pressure to hold clean elections next year. This month, he held a domestic referendum in which voters backed his contention that the contested terrain is an essential part of Venezuela.

At the urging of Brazil and other nations, Maduro met Thursday with Guyana’s president, Mohamed Irfaan Ali, in the Caribbean island nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. “The priority is peace,” Ali said in a statement. Maduro declared on X, formerly Twitter: “Dialogue is the mechanism for understanding and the preservation of Peace in Venezuela.”

But the meeting left little resolved in a conflict about land, oil, minerals and sovereignty that has sounded alarm bells throughout the region.

Here are the details:

What’s the backdrop behind the dispute?

Venezuela is home to some of the world’s largest oil reserves. But its once-robust economy cratered and millions of impoverished Venezuelans have emigrated, especially since the 2017 mass protests against the rule of Maduro, a protege of ex-President Hugo Chávez and a fervent adversary of the United States.

Maduro blames his country’s woes on U.S. sanctions that have helped cripple Venezuela’s petroleum sector. Washington calls Maduro a dictator whose mismanagement has wrecked Venezuela’s economy and battered the country’s oil-and-gas extraction infrastructure — and caused misery for many of the country’s 30.5 million residents.

Guyana, a staunch U.S. ally, is a former Dutch and British colony that is home to a small but extremely diverse population of 800,000 — including descendants of African slaves and indentured workers from the Asian subcontinent, Indigenous peoples and settlers from Europe and elsewhere. It is the sole nation on the continent where English is the official language.

Venezuela’s government says voters OK’d a referendum pushed by President Nicolás Maduro to claim sovereignty over much of its oil-rich neighbor Guyana.

Guyana is perhaps best-known in the United States as the site of the 1978 murder-suicide of more than 900 people linked to the California-based Peoples Temple cult and its wayward leader, Jim Jones.

Guyana’s economy long featured relatively small-scale farming, fishing, timber-harvesting and mining. But the once-quiescent economy has been super-charged since discoveries in 2015 of huge offshore oil deposits.

What is Essequibo?

The sprawling swath of jungle, savanna and coast named after the Essequibo River — which forms the region’s eastern boundary — accounts for two-thirds of Guyana’s land. At 61,000 square miles, it’s an area slightly smaller than Florida.

The border dispute with Venezuela dates to the early 1800s and British Guiana, as pre-independence Guyana was known. An 1899 international arbitration decision affirmed that Essequibo was part of British Guiana, but Venezuela has long said the process was rigged and that its dominion over Essequibo stretches back centuries to Spanish colonial days. Guyana gained independence in 1966.

Guyana’s president tells the Associated Press his country is taking every necessary step to protect itself from Venezuela over disputed area.

The Essequibo area, rich in timber and minerals, is now helping to transform Guyana through the recent oil boom.

In 2018, with an offshore drilling frenzy well underway, Guyana moved to secure an international imprimatur for control of Essequibo, taking its case to the International Court of Justice (sometimes called the World Court), the United Nations’ highest judicial panel. In April, the court rejected procedural objections from Venezuela, paving the way for the justices to hear arguments from both sides.

What steps has Venezuela taken?

The World Court ruling stung Venezuelan officials, even though a final decision is probably years off.

Maduro was left with “a ball of fire in his hands,” said Jesús Seguías, an independent political analyst in Caracas. A court declaration that Essequibo is part of Guyana would be a humiliation for a president already on shaky electoral ground, said Seguías.

But Maduro, a survivor of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign to drive him from office, struck back. He called a nationwide referendum on a plan to incorporate Essequibo into Venezuela and deny World Court jurisdiction.

The International Court of Justice on Dec. 1 ordered Venezuela not to do anything to alter the status quo on Guyana’s control over Essequibo. But it denied Guyana’s bid to ban the referendum.

Many analysts saw Maduro’s moves as a ploy ahead of next year’s elections.

“This is really about Venezuelan domestic politics,” said Geoff Ramsey, a senior analyst with the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank. “Maduro is trying to make up for falling popularity by stoking nationalism.”

The Venezuelan government said more than 95% of voters approved the referendum. But images of sparsely attended polling stations led many to question the official account that 10 million people cast ballots.

The U.N.-backed panel says human rights violations to curtail democratic freedoms in Venezuela have intensified ahead of the 2024 election.

Among those voting was Carlos Herrera, 60, a Caracas plumber who agreed that Essequibo belonged to Venezuela — but said the matter should be resolved peacefully. “Maduro will do whatever he can to avoid confronting the country’s real problems,” Herrera said. “Poverty is our main problem. One doesn’t win wars with hunger.”

Following the vote, Maduro unveiled an expansive blueprint for a new Venezuelan state of Essequibo, ordered Venezuela’s state energy and mineral concerns to begin preparations to work there, and launched the process to grant Venezuelan citizenship to the region’s 125,000, mostly English-speaking residents. He presented a multicolored map incorporating the disputed territory inside Venezuela’s boundaries.

Venezuela dispatched a military contingent to the Atlantic coast, close to the disputed area, and named a major-general as provisional authority in the area.

Although Maduro gave companies working in Essequibo three months to leave, ExxonMobil declared Tuesday on its Guyana Facebook page: “We are not going anywhere.”

The government of Guyana, under pressure from neighboring Brazil and a Caribbean trading bloc, has agreed to join bilateral talks with Venezuela.

How has Guyana responded?

Guyana’s leadership has denounced what it calls an illegal land grab threatening regional stability. President Ali labeled Venezuela an “outlaw nation” andstressed that his country would seek outside aid to thwart any more provocations.

“Should Venezuela proceed to act in this reckless and adventurous manner, the region will have to respond,” Ali told the Associated Press.

He reiterated Thursday that Guyana wants the issue settled via the International Court of Justice. In his statement, Ali said he “made it clear” to Maduro “that the controversy must be resolved at the ICJ and we are unwavering and resolute in ensuring that Guyana’s case is presented and defended.” Venezuela rejects the court’s authority in the case.

How have other countries reacted?

U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken reaffirmed Washington’s position that Guyana has full sovereignty over Essequibo and White House officials have said they were monitoring the situation.

The U.S. military’s Southern Command said it would conduct flight operations in collaboration with Guyana’s military — a move denounced as a “provocation” by Caracas.

Brazil, which shares northern borders with Venezuela and Guyana, said it was bolstering its military presence along its northern frontiers.

No country has absorbed more Venezuelan migrants than Colombia, which has a long, complex and often fractious relationship with its next-door frenemy.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has tried to broker a solution, declared: “What we don’t want here in South America is war.”

Some observers suspect Maduro could be seeking a pretext to declare a national emergency and call off next year’s election.

Is military action by Venezuela a realistic possibility?

Most observers say Venezuela is unlikely to launch a military strike. Even though its 100,000-plus troops far outnumber Guyana’s meager defense array, the logistical hurdles are considerable: A full-scale ground invasion is not practical, experts say, since much of the Essequibo frontier with Venezuela is near-impenetrable rain forest and swamps. That leaves the faint possibility of an air or marine assault.

A Venezuelan attack could trigger an armed response from allies of Guyana. It would also probably further isolate Venezuela when Caracas is agreeing to electoral reforms and cooperating with Washington on immigration strategy in a near-desperate effort to convince the White House to relax sanctions. The oil boom in Guyana has dramatized how much Venezuela needs outside expertise and investment to revitalize its own oil industry.

“Neither Venezuela or Guyana want to see this expand into a full-blown conflict,” Ramsey said. “This is much more about saber-rattling than a real threat.”

What’s next?

There had been little expectation that Thursday’s meeting between Maduro and Ali would yield anything close to a resolution. Ali said Thursday that although both countries want peace, Guyana “is not the aggressor.”

During a news conference in a break in the meeting, he pointed to a thick leather bracelet on his right wrist featuring the outline of Guyana, including the disputed Essequibo region.

“All of this belongs to Guyana,” Ali said. “No narrative propaganda [or] decree can change this. This is Guyana.”

Times staff writer McDonnell reported from Mexico City and special correspondent Mogollón from Caracas.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.