- Share via

LEWISTON, Maine — In a small park along the mighty Androscoggin River, Leroy Walker Sr. stood in a neon yellow jacket at the base of a bell tower, his hair thinning at the top of his head. He greeted family after family, exchanging hugs with some parents, as children set off into the candyland awaiting them at Auburn’s annual trick-or-treating event.

“Good luck — you’ll fill that bucket,” Walker, an Auburn City Council member, said to a young boy dressed as a dinosaur.

From afar, Sunday looked and sounded like any other bone-chilling Halloween in Maine: “Ghostbusters” played over speakers while children dressed as Pokemon, Buzz Lightyear, scarecrows, Dalmatians and more loaded their pumpkin buckets and candy bags full of sugar.

Yet across the river in Auburn’s sister city of Lewiston, workers in hazmat suits and high-grade masks were scrubbing concrete steps at the far end of Schemengees Bar & Grille, where dozens of cars were still parked in the lot, some with evidence tape covering their windows.

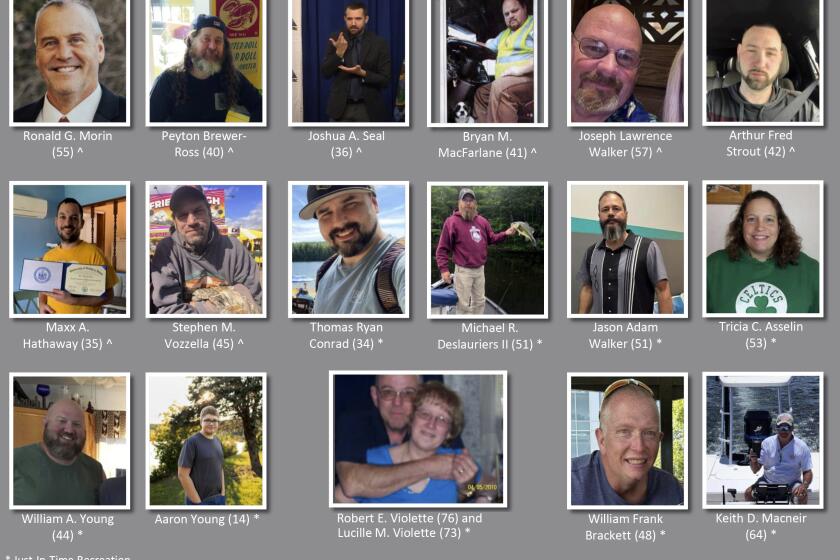

Authorities have identified the 18 people killed this week when a gunman opened fire at a bowling alley and restaurant in Lewiston, Maine. Here are their stories.

Days earlier, a gunman had opened fire in Schemengees minutes after unleashing a volley of bullets inside Just-In-Time bowling alley in another stretch of Lewiston, all before disappearing into the night.

Eighteen people were killed in the shootings, including Walker’s son Joseph. Authorities said he was slain as he used a butcher’s knife to try to stop the shooter.

“If my son was here, we’d be side by side,” Walker said. People often called them twins, because Joey “wanted to be just like dad,” he said.

Lewiston is a weathered town that has seen dark days, but this heartache was unprecedented. For 48 hours, residents were on edge as authorities searched for the gunman, forcing them to hunker down while searchlights flooded their homes, helicopters circled overhead, sirens blasted through the night and the woods they’d known their whole lives suddenly became dangerous and foreign.

Under shelter-in-place orders, many anxious members of the community had to grieve the bloodshed in isolation.

But at Sunday’s trick-or-treat event and other moments across Lewiston-Auburn and the neighboring areas, residents — traumatized and shaken but full of resolve — took their first steps toward processing the tragedy together as a community.

Maine’s authorities are trying to piece together the events that led to the worst mass shooting in the state’s history.

“After being cooped up and dealing with the events separately, we can deal with the aftermath together,” said Alanna Larrivee, 28, who attended a Saturday night vigil in Lisbon, near the area where the shooter was found dead late Friday of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound, ending a harrowing manhunt.

Like those in so many American towns before them, residents embraced and wept with one another at vigils. They lighted candles for the victims and survivors, including 13 injured, and shielded the flames from the autumn winds. They placed flowers and notes where the shootings occurred. They talked in grocery store aisles about how beloved the bowling alley and restaurant were, how that could have been them caught in the gunfire. They expressed disbelief and anger that something so vile, so ugly could happen in Lewiston.

“I don’t think we’ll be remembered for this one senseless act,” Tim Cassidy of Auburn said after putting flowers down outside Schemengees, where he played pool for years and knew the owners and some of the victims, including Joey Walker. “It won’t be forgotten, but it won’t define this city.”

In its mourning, the community has also made uncommon space for the gunman’s family, who raised concerns to the local sheriff about his mental health months before the massacre. Mainers have prayed for the family at vigils, dropped off flowers and expressed their sadness for a troubled man and lost soul in desperate need of help.

Walker, who is deeply religious, has said he doesn’t have hate in his heart for the shooter.

At one Sunday morning Mass, Father Elaiyaraja Thaniyel, known as Father Raja, focused his homily on eternal love. That afternoon, he led a prayer service where framed photos of the 18 victims stood on the steps leading up to the altar at Holy Family Church along with candles and white roses.

Parishioners’ voices filled the belly of the church with prayers and songs, led by the soaring voice of a singing pianist. From one of the first pews, Tim Conrad held a long salute when the priest recited the name of his son, Thomas Conrad, a 34-year-old Army veteran who managed the bowling alley and who friends said died while trying to take down the gunman.

“Nothing is affecting the bond of love I have seen in the people,” Father Raja said. “Though there’s pain, we still remain strong.”

Police have not declared a motive in the mass shooting by Robert Card, whose body was discovered Friday.

That word has become a popular refrain here: “Lewiston Strong,” banners and hand-painted signs say — reflecting not just the city’s history but also residents’ solemn promise to their community’s future.

As the weekend passed and the police tape blocking off the streets was lifted, the memorials outside the establishments grew.

Just-In-Time, long known in the community by its former name, Sparetime Recreation, looks like a church, with a large, arched window facing a quiet street occupied mostly by other businesses and parking lots. And to the many regulars who came for games of cornhole and bowling, being there was almost an act of devotion.

But now, the building was dark. A chaplain’s bus sat in the parking lot. At the edge of the grass was a line of pumpkins, some painted black, carved with reminders of Lewiston’s resilience. Bouquets of purple and pink chrysanthemums and blue crosses decorated the grounds.

Cars slowed to a stop as people got out to pay their respects. Dan Corriveau parked his motorcycle and bent over on the grass in prayer. Corriveau said he knew Tricia Asselin, who was killed as she ran to get her phone and call 911. He and his wife provided child care for her son when he was growing up.

For some, the weight of the tragedy elicited sadness and anger, along with a new purpose.

“I want to go to Congress and yell: Ban assault weapons!” an impassioned Denis Bouttenot cried out. “You don’t need them in public hands.”

Bouttenot’s wife, Evette, knew Lucille M. Violette, who visited the bowling alley every Wednesday with her husband, Robert. The Violettes were both killed; Robert, who coached a youth bowling league, died trying to shield children, witnesses said. Lucille died at the hospital.

Four miles away, a similar outpouring of crosses, flowers and signs filled various points along the road to Schemengees, where survivors were slowly going to pick up their cars. Many pulled out of the parking lot without looking back.

Dave and Jody Madore walked up Lincoln Street with their 8-year-old daughter, Cadence, her white heels clacking against the asphalt. Dave Madore owns the arcade and jukeboxes inside the restaurant, where he was supposed to be Wednesday night to fix a jukebox that was on the fritz. “If it weren’t for a phone call, I would have been there,” said Madore, who knew many of the victims.

Thousands of people packed the pews at the Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul for a vigil Sunday, while hundreds watched a livestream set up on a screen outside the church. Attendees bowed their heads in silence; they sang “Amazing Grace” as musicians played cello and violin. Kevin Bohlin signed the names of the four victims from the area’s Deaf community who were killed. The congregation joined him in signing “I love you.”

Though there was space reserved for him in the basilica, Walker watched the vigil from outside. Before arriving, he met with one of Schemengees’ owners, and he could feel his son Joey’s presence around them, he said. When he saw the crowds spilling out onto Ash Street and heard the messages of love and hope from the pulpit, he felt his son even more.

“Every time [someone hugged me], in my mind I was blessing my son,” said Walker, who is planning a vigil in Auburn for this week.

In the days since he lost his son, Walker, who also lost a daughter 25 years ago to a car crash, has prayed to God, asking for the power to bring Joey back.

He knows it’s not possible, Walker said, but still, “I have to ask.”

Earlier that day, at the trick-or-treat festival, Walker choked up and pointed toward a bald man walking down 2nd Street with his family. For a brief moment, Walker thought it looked like Joey, gesturing toward his head.

Walker composed himself and fought back tears. Then he turned back to greet more families with their own children in tow, eager to celebrate Halloween together again.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.