Inside the growing cult of El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, Latin America’s political star

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — In Peru, there is talk of building a monument in his honor.

In Honduras and Ecuador, leaders have copied his draconian security policies, his tough-on-crime rhetoric — and even his fashion choices.

In Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia and Guatemala, citizens have taken to the streets calling on their own governments to embrace his extreme strategies for combating violence.

Latin America has a new hero on the right: the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele.

The brash young autocrat has won legions of fans throughout the region for a sweeping crackdown on gangs that has dramatically lowered violent crime. That his “mano dura” policies draw scorn from human rights and democracy advocates seems to only feed his cult-like status as a renegade willing to get things done, whatever the cost.

“He is a role model,” said Diego Uceda Guerra-García, the mayor of a district in Lima, Peru, who has called for stiffer laws and longer prison sentences, and who hopes to build a public park in Bukele’s name. “He has put an end to the scourge. In countries like ours where there is a lot of ignorance and a lot of underdevelopment, sometimes we have to be a bit heavy-handed. Half-measures do not work.”

One recent poll showed that Bukele was twice as popular among Ecuadoreans as any of their own politicians — a sentiment that appears common across the continent.

The cult of Bukele is part of a recent surge of populist outsiders worldwide and reflects the degree to which crime has become a major anxiety across Latin America. Already facing the highest homicide rate in the world, the region has seen an increase in violence, including some nations that until recently were relatively peaceful.

With his carefully crafted social media presence and populist politics, Nayib Bukele has become one of the most popular politicians on Earth. Now just one question remains: What does he want?

“If Bukele was able to subdue crime in El Salvador, why are security policies less effective in other countries?” asked the Colombian magazine Semana, which recently devoted its cover to the Salvadoran leader with the headline: “The miracle of Nayib Bukele.”

“That is the question that millions of people ask themselves.”

Bukele, a 42-year-old former marketing executive who prefers TikTok to traditional media, has described himself both as an “instrument of God” and the “world’s coolest dictator.”

Since taking office in 2019 on a pledge to squash corruption and break with the country’s entrenched political parties, he has consistently courted controversy, verbally sparring with the U.S. ambassador, tweeting “Simpsons” memes at the International Monetary Fund and making El Salvador the first country to adopt bitcoin as legal tender.

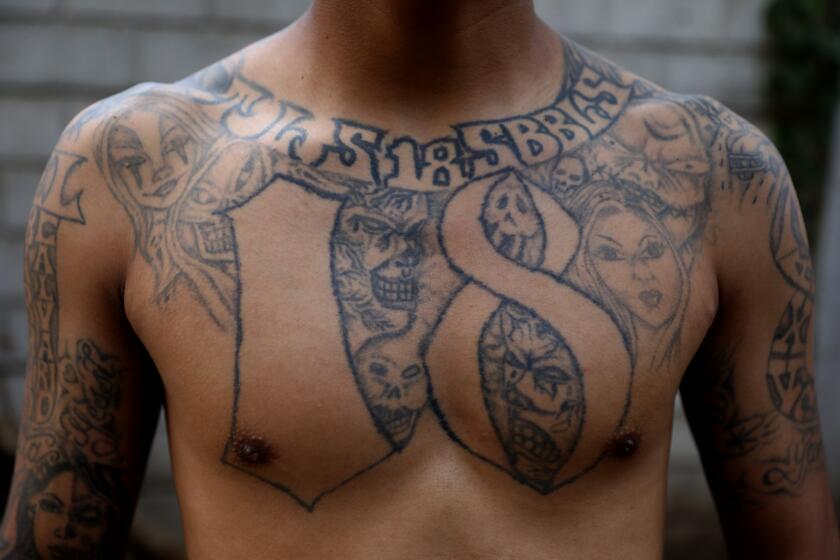

Faced with some of the highest homicide rates in the world and the decades-long dominance of the MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs, his government first tried to contain the violence by secretly negotiating a truce with gangsters. When that broke down last year, Bukele declared a state of emergency that suspended civil liberties as authorities jailed more than 70,000 people — about 2% of the country’s adult population — in a matter of months.

El Salvador’s evangelical churches rehabilitated ex-gang members. The country’s crackdown on L.A.-born gangs like MS-13 emptied programs and filled prisons.

Human rights groups cried foul, citing due process violations, the deaths of dozens of inmates and the imprisonment of children as young as 12. At the same time, critics cited an escalating series of anti-democratic power grabs as evidence that Bukele was embracing authoritarianism.

Yet as homicides plunged, Bukele’s approval ratings skyrocketed.

Today 93% of Salvadorans endorse his presidency, one of the highest rates in the world. And 9 out of 10 support Bukele’s campaign for reelection next year — even though the constitution prohibits consecutive presidential terms.

With that kind of popularity, experts say, it’s no wonder there are so many regional copycats.

In Argentina and other Andean nations, Bukele’s face now appears in the campaign advertisements of candidates hoping to exploit his political capital. Some politicians, including Colombia’s presidential runner-up, Rodolfo Hernández, have made pilgrimages to El Salvador to observe for themselves the cult of “Bukelismo.”

Politicians throughout the region have also begun mimicking his style — aviator sunglasses, leather bomber jackets, baseball caps.

Journalists in El Salvador who write about gangs can now be sent to prison. Two brothers defy the law with a story tying President Nayib Bukele to violent street gangs.

Consider Jan Topíc, a candidate in next month’s presidential election in Ecuador, whom local media describe as the “Ecuadorean Bukele” for his carefully shaped beard, his propensity for leather jackets and his outspoken support for the Salvadoran leader.

“Everybody wants to be a Bukele,” said Steven Levitsky, director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University, who added that the Salvadoran is one of the most revered politicians in the region since Hugo Chávez, a socialist who led Venezuela until his death in 2013.

Though he hails from the opposite end of the political spectrum, Bukele, like Chávez, is a populist and an autocrat, and his appeal has raised similar concerns about the fate of democracy on a continent still grappling with a long history of dictatorships.

Levitsky, who is co-author of the 2018 bestselling book “How Democracies Die,” said it’s no accident that Bukele’s ascent has coincided with a rise in crime across many parts of Latin America.

“Security pushes people to the right, almost invariably, and pushes voters in a more authoritarian direction in the sense that they’re willing to accept violations of human rights, civil liberties and rule of law,” Levitsky said. “People across the world are willing to sacrifice a lot of liberal democratic niceties for security.”

Brian Winter, editor in chief of Americas Quarterly magazine, recently wrote that violent crime may be replacing government corruption as the most important issue for voters in Latin America.

“Violent crime is dominating the political debate,” he said, citing polls in multiple countries in which voters named crime as the most important issue.

With more than 6,000 people held after a weekend killing spree, El Salvador’s president and his congressional allies have put civil liberties on hold.

That includes nations long considered safe, such as Chile, where homicides have doubled over the last decade, and Ecuador, where the growing cocaine trade has unleashed record levels of bloodshed.

Ecuador’s president, Guillermo Lasso, recently lifted a ban on civilians carrying firearms and has declared states of emergency that have elicited comparisons to Bukele’s efforts in El Salvador.

Even some leaders on the left are embracing Bukele-style policies.

As a candidate, Honduran President Xiomara Castro vowed to adopt a community-oriented approach to public safety and reform the nation’s famously corrupt security apparatus. But since taking office last year, she has given security forces more power, imposing a state of emergency that involves the suspension of some constitutional rights. Last month, she authorized a prison crackdown nearly identical to one ordered by Bukele last year.

El Salvador’s president has threatened to stop providing food for imprisoned members of street gangs.

Just as in El Salvador, authorities in Honduras performed a sweep of prisons, ostensibly searching for contraband, and later published images of tattooed inmates being subjected to humiliations in their underwear. Like Bukele, Castro has begun wearing aviator sunglasses.

“The aesthetics of Bukelismo are definitely taking the region by storm,” said Will Freeman, a fellow for Latin American studies at the Council for Foreign Relations, who said Bukele has fashioned himself as the second coming of Francisco Morazán, the 19th century Honduran leader who served as president of a short-lived federation of Central American nations formed after independence from Spain. Unlike Bukele, he was known as a champion of individual liberties.

In Honduras, where gangs extort money from business owners, truck drivers and even students, many say they would like the Castro government to go even further in Bukele’s direction.

“He’s an example for all of us in Central America,” said Glenda Pineda, a 51-year-old accountant at a paint store in San Pedro Sula.

“We can’t stand the violence any more,” she said. “The little bit a shopkeeper earns, he has to share with one, two, sometimes three gangs.”

The new state of emergency and recent prison raids were a good start, she said: “But I think it has to be a lot harsher.”

Sandra Torres, the front-runner in next month’s presidential runoff in Guatemala, says she too sees El Salvador as a model. “I plan to implement President Bukele’s strategies,” Torres said. “They are working.”

Bukele’s policies have also found fans in the United States.

Salvadorans have organized street marches in his favor in Los Angeles. In Washington, Republicans have lambasted the Biden administration for leveling sanctions against members of Bukele’s government, including the nation’s prisons chief, who is accused of negotiating with gang leadership to provide political support to Bukele’s party, New Ideas.

“It’s absurd to criticize [Bukele] for giving Salvadoran people their freedom back,” said Marco Rubio, the Republican senator from Florida, who met with Bukele in El Salvador this spring. “The left is so allergic to law enforcement that it would rather see Barrio 18 and MS-13 roaming the streets than criminals locked up.”

While analysts say Bukele is almost guaranteed to win a second term, they point to problems on the horizon: namely the country’s steep foreign debt. Many have also questioned how long his regional influence will endure, given that his strategy for fighting crime in El Salvador, a nation of 6.5 million people that is smaller in size than Massachusetts, would be difficult to replicate elsewhere.

Four months into El Salvador’s bitcoin experiment, few use the cryptocurrency, fraud has been widespread, and the country has lost up to $22 million.

And along with praise for Bukele, there is also growing fear.

For the record:

2:55 p.m. July 25, 2023An earlier version of this article misspelled the first name of Chilean novelist Isabel Allende as Isabella.

Chilean novelist Isabel Allende recently weighed in on the Bukele phenomenon, telling El País newspaper that she’s afraid that the continent could drift back to the era when it was governed by strongmen such as Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

“I am very afraid that people will exchange security for democracy,” Allende said. “In Chile now people are longing for a Bukele. I say: Be careful. That was Pinochet. There was security in those days. But the insecurity and terror came from the state, not from the criminal who walks the street.”

Colombian President Gustavo Petro, a former leftist guerrilla fighter who has described El Salvador as a “concentration camp,” said recently on Twitter that the best way to reduce homicides wasn’t with “gruesome” security policies but with “universities, schools, spaces for dialogue, spaces for poor people to stop being poor.”

“Here in Colombia we deepen democracy, we do not destroy it,” he said.

“I don’t understand his obsession with El Salvador,” Bukele responded. “Is everything okay at home?”

He later retweeted the results of a poll that found whereas 32% of Colombians approved of Petro, 55% would like a president like Nayib Bukele.

“I think I’ll go on vacation to Colombia,” he wrote.

Special correspondents Shanna Taco in Lima and Paulo Cerrato in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.