Appeals court says British plan to send asylum-seekers to Rwanda is unlawful

- Share via

LONDON — A British court ruled Thursday that a plan to send asylum-seekers on a one-way trip to Rwanda is unlawful, delivering a blow to the Conservative government’s pledge to stop migrants making risky journeys across the English Channel.

In a split 2-1 decision, three Court of Appeal judges said Rwanda could not be considered a “safe third country” where migrants could be sent.

But the judges said that a policy of deporting asylum-seekers to another country was not in itself illegal, and the government said it would challenge the ruling in the Supreme Court. It has until July 6 to lodge an appeal.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said that, “while I respect the court, I fundamentally disagree with their conclusions.”

Sunak has pledged to “stop the boats” — a reference to the overcrowded dinghies and other small craft that make the journey from northern France carrying migrants who hope to live in Britain. More than 45,000 migrants arrived in England from across the Channel in 2022, and several died in the attempt.

The British and Rwandan governments agreed more than a year ago that some migrants who arrive in the U.K. as stowaways or in small boats would be sent to Rwanda, where their asylum claims would be processed. Those granted asylum would stay in the East African country rather than return to Britain.

The number of people moving to Britain reached a record high in 2022, renewing debate about the scale of immigration and its impact on the country.

The British government argues that the policy will smash the business model of criminal gangs that ferry migrants on hazardous journeys across one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Human rights groups say it is immoral and inhumane to send people more than 4,000 miles to a country they don’t want to live in, and argue that most channel migrants are desperate people who have no authorized way to come to Britain. They also cite Rwanda’s poor human rights record, including allegations of torture and killings of government opponents.

Britain has already paid Rwanda about $170 million under the deal, but no one has yet been deported there.

Britain’s High Court had ruled in December that the policy was legal and didn’t breach Britain’s obligations under the United Nations Refugee Convention or other international agreements, rejecting a lawsuit from several asylum-seekers, aid groups and a border officials’ union.

Rescuers were dispatched to save passengers of a small vessel that capsized in the English Channel, which 44,000 migrants have tried to cross in 2022.

But the court allowed the claimants, who include asylum-seekers from Iraq, Iran and Syria facing deportation under the government plan, to challenge that decision on issues including whether the plan is “systemically unfair” and whether asylum-seekers would be safe in Rwanda.

In a partial victory for the government, the appeals court ruled Thursday that Britain’s international obligations did not rule out removing asylum-seekers to a safe third country.

But two of the three judges ruled that Rwanda was not safe because its asylum system had “serious deficiencies.” They said asylum-seekers “would face a real risk of being returned to their countries of origin,” where they could be mistreated.

Lord Chief Justice Ian Burnett — the most senior judge in England and Wales — disagreed with his two colleagues. He said assurances given by the Rwandan government were enough to ensure that the migrants would be safe.

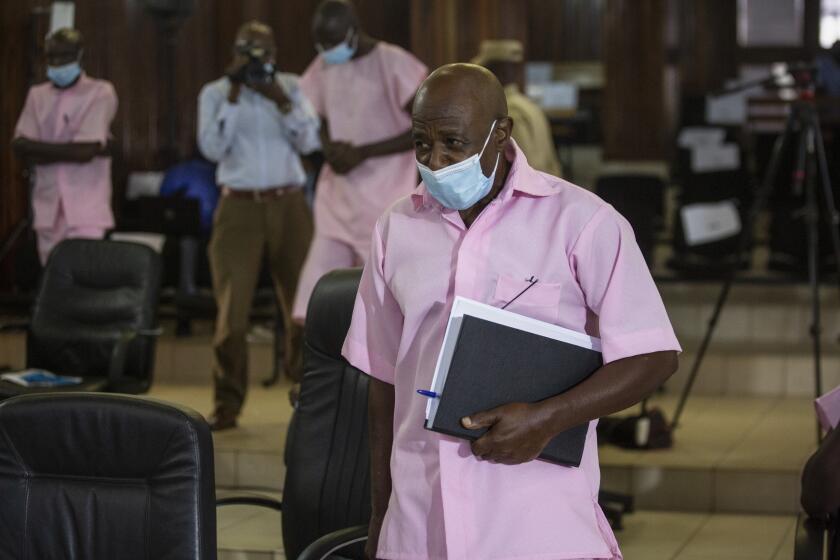

Rwanda’s government has commuted the 25-year sentence of Paul Rusesabagina, who inspired the film “Hotel Rwanda” for saving hundreds of countrymen.

The government of Rwanda took issue with the ruling, calling itself “one of the safest countries in the world.”

“As a society, and as a government, we have built a safe, secure, dignified environment, in which migrants and refugees have equal rights and opportunities as Rwandans,” government spokeswoman Yolande Makolo said. “Everyone relocated here under this partnership will benefit from this.”

However, Rwandan opposition leader Frank Habineza said Britain should not seek to offload its responsibilities for refugees.

“The U.K. is a bigger country than Rwanda, [has] huge resources, unlike impoverished Rwanda,” he said. “Sending migrants to Rwanda, the U.K. will be relinquishing responsibility of protecting those running to the U.K. for safety.”

The interior ministers of France and Britain have agreed to a deal aimed at curbing migration across the English Channel.

Yasmine Ahmed, U.K. director of Human Rights Watch, said the verdict was “some rare good news in an otherwise bleak landscape for human rights in the U.K.”

She urged Home Secretary Suella Braverman, the minister in charge of immigration, to “abandon this unworkable and unethical fever dream of a policy and focus her efforts on fixing our broken and neglected migration system.”

Even if the plan is ultimately ruled legal, it’s unclear how many people could be sent to Rwanda. The government’s own assessment acknowledges that it would be extremely expensive, coming in at an estimated $214,000 per person.

But it is doubling down on the idea, drafting legislation barring anyone who arrives in Britain in small boats or by other unauthorized means from applying for asylum. If passed, the bill would compel the government to detain all such arrivals and deport them to their homeland or a safe third country.

“It is this country — and your government — who should decide who comes here, not criminal gangs,” Sunak said. “And I will do whatever is necessary to make that happen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.