Experts’ repeated warnings about Titan’s construction will be key part of investigation into sub’s implosion

- Share via

NEW YORK — Long before the OceanGate Expeditions Titan submersible embarked on its final, doomed voyage, oceanographers, engineers, industry experts and a former employee set off alarms about the vessel, warning that its design could lead to serious consequences without standard, rigorous testing.

The role those factors may have played in the vessel’s “catastrophic implosion” during its journey to the sunken wreckage of the Titanic, which killed everyone on board and brought a tragic end to a days-long search that became a national fixation, is now in the crosshairs of an unfolding investigation that is likely to focus in part on industry safety standards, officials have said.

Few official details have emerged about the scope of that investigation. It remains unclear what country will take the lead in probing the catastrophe, which happened in international waters and affected different nations.

“There’s a lot of questions about why, how and when this happened,” U.S. Coast Guard Rear Adm. John Mauger told reporters Thursday.

The five people aboard a submersible that vanished on a trip to explore the Titanic wreckage have died after a catastrophic implosion, the U.S. Coast Guard says.

But for those familiar with the Titan’s design and operations, safety concerns long predated the disaster. OceanGate declined to provide any additional comment beyond the company’s statement Thursday.

In 2018, an OceanGate employee raised flags about the vessel in litigation with the company, particularly its refusal to undergo external review and subject passengers to dangers. That same year, dozens of submersible industry experts warned company chief executive Stockton Rush in a letter that the vessel’s “experimental” approach could have “minor to catastrophic” consequences. They pressed him to undergo a rigorous review from classification societies like the DNV or the American Bureau of Shipping for the Titan.

“While this may demand additional time and expense, it is our unanimous view that this validation process by a third-party is a critical component in the safeguards that protect all submersible occupants,” the letter stated.

Liz Taylor, president of Deep Ocean Exploration and Research, or DOER Marine, which designs and builds remotely operated vehicles, said that the submersibles industry has maintained an unblemished safety record while accomplishing many firsts. “The way you do it is you do the work, you do the testing,” Taylor said. But Rush did not want to hear it, she added.

“He ostensibly felt that he had done enough or knew better,” she said.

Rush openly pushed back against criticism. Safety regulations helped the industry avoid accident or injuries, he said, but they also stifled growth and adventure. “One of the jabs that gets thrown at us is: ‘Hey, you aren’t certified.’ But how can you do something new and get certified?” Rush asked in a 2022 article in Maptia. Referring to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, he added: “I think it was MacArthur who said, ‘You are remembered for the rules you break.’ We try to break the rules intelligently and intentionally.”

Rush was the pilot of this week’s expedition. Officials said he died along with four passengers: Hamish Harding, chairman of Action Aviation, a Dubai-based aircraft dealer; Paul-Henry Nargeolet, a veteran and accomplished diver with more than 30 trips to the Titanic wreck site; Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood and his son, Suleman.

What caused Titanic tourist sub to implode, killing all five aboard? Officials look for clues.

“It’s not just that you get certified once and you just keep using your craft and taking it on any number of expeditions,” said Dawn Wright, a marine geologist and chief scientist of the Environmental Systems Research Institute who traveled to the deepest known point of Earth’s seabed last year aboard the Limiting Factor submersible. “It’s like getting an oil change for your car. You maintain it, you give it tuneups and oil changes. You keep it safe and keep it in proper working order.”

Submersibles are typically made using titanium, steel and, depending on how deep they’re planned to travel, acrylic. All those have been proved to withstand changes in water temperature and the crushing pressure of the ocean depths.

Vessels are commonly sphere-shaped to more evenly distribute that pressure, which multiplies rapidly the further down you dive.

By contrast, the 21-foot Titan had a carbon fiber composite hull with titanium end caps and was shaped like a tube — an approach that was more affordable and accommodated more passengers, at the price of around $250,000 a head.

Experts say that the Titan’s unconventional design did not undergo a meticulous external review process left it vulnerable and dangerous.

The water pressure at the depth of the Titanic, which is about 12,500 feet, is nearly 400 times greater than that at sea level. Carbon fiber, which can maintain internal pressures, can be unstable under external pressure, susceptible to experiencing small cracks that can become catastrophic. The combination of various materials, which risked responding differently to the ocean’s changes in pressure and temperature, were also a concern.

“You have this thing that is supposed to stick together and keep the ocean out, but [the materials are] shrinking at different rates,” said Harvard marine scientist Peter Girguis, who has been on several deep sea dives throughout his career.

Alfred Hagen has taken two voyages on the Titan submersible, which is now missing near the site of the Titanic shipwreck. He describes what the conditions might be like onboard.

Ships and other vessels adhere to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, a global treaty established in 1914, in a grim sort of irony, in the immediate aftermath of the Titanic. But there is no global standard for submersibles, which means they operate in a gray area when they’re in international waters, said Salvatore Mercogliano, an associate professor of maritime history at Campbell University in North Carolina.

“It’s the wild, wild west,” he said.

The Titan departed from Canada, was loaded onto a Canadian ship and launched into a remote area of the North Atlantic. As such, it did not need to register with a country, fly a flag or observe regulations set for other kinds of vessels, according to Mercogliano.

“It’s kind of like putting a boat on the back of a trailer and towing it with your car,” he said. A police officer who pulls you over might ask to see license and registration for the car or trailer, he said, but “they don’t care about the boat, because it’s not their jurisdiction.”

That is also why the 1993 Passenger Vessel Safety Act, an American law that essentially lays out the requirements for when a submersible carrying passengers needs to register with the Coast Guard, does not cover the vessel, he said.

Bill Price took a voyage with OceanGate to the ruins of the Titanic. He’s reckoning now with the loss of two men he deeply respected.

In 2019, OceanGate published an online blog post, “Why Isn’t Titan Classed?” According to the post, which appears to have been deleted, industry standards focus only on “validating the physical vessel.”

“They do not ensure that operators adhere to proper operating procedures and decision-making processes — two areas that are much more important for mitigating risks at sea,” the blog post stated.

Some experts, though, said the Titan did not have even basic contingency plans. Most vessels that conduct high-risk operations will have a type of emergency locator beacon that could send a signal to anyone with access to that frequency, including the Coast Guard, and allow them to respond, according to Aaron Davenport, a retired U.S. Coast Guard officer. The Titan did not appear to have such a beacon, he said.

Taylor said classing submersibles also addresses standard operational and emergency procedures. One such standard, especially when working in remote areas, was to have a self-rescuing capacity on site, ready-to-go, she said. “There was none of that, in this case,” she said. The vessel did not even file a plan with the Coast Guard, which she called “normal procedure.”

Before Taylor launches a sub, she makes calls to different assets in the area to inform them of her plans and learn what resources might be available.

“If we can’t check all the boxes off, then it’s a no-go,” Taylor said.

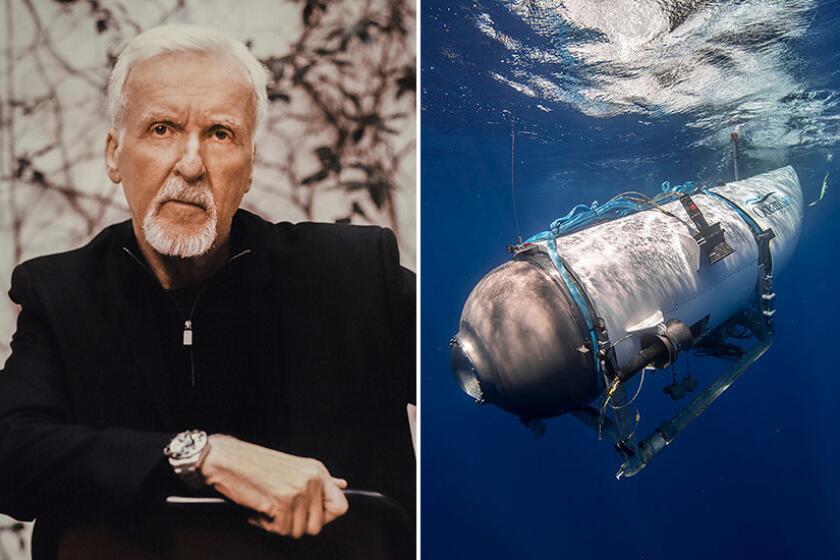

OceanGate co-founder Guillermo Söhnlein defended his former company and the Titan submersible against James Cameron’s criticism of the sub’s design.

Another critic has been “Titanic” director James Cameron, who spent more than 30 days down at the ship’s wreckage and helped design a submersible he later piloted to the deepest point in the world’s oceans. He told Reuters he wished he had sounded the alarm earlier, adding that he had been skeptical when he heard OceanGate was making a deep-sea submersible with a composite carbon fiber and titanium hull.

“I thought it was a horrible idea,” Cameron said. “I wish I’d spoken up, but I assumed somebody was smarter than me, you know, because I never experimented with that technology, but it just sounded bad on its face.”

OceanGate co-founder Guillermo Söhnlein has appeared on various news outlets defending the company and responding directly to Cameron’s comments. There are a multitude of opinions on how to build submersibles and operating dives, he said. He called it “impossible” for anyone not involved in OceanGate’s processes to speculate.

“This was a 14-year technology-developed program, and it was very robust and certainly led to successful scientific expositions to the Titanic in the last few years,” he said in a separate interview on BBC Radio 4 on Friday.

The Coast Guard said Thursday they discovered wreckage from the Titan using remote-operated vehicles capable of searching the seafloor. The debris was consistent with “catastrophic loss of the pressure chamber,” said Mauger.

Robots have continued to comb the seafloor for debris in an effort to construct a timeline of the vessel’s final hours. Regulations and standards are likely to be the “focus for future review,” Mauger said.

The exploitative coverage of the death and terror unfolding in real time as the search for the Titan sub continued was compounded by the public’s reaction on TikTok and Twitter.

Coast Guard officials said they found several major pieces of the vessel in a debris field about 1,600 feet away from the bow of the Titanic, including the nose cone, the front end of the pressure hull and the back end of the pressure hull.

OceanGate Expeditions, the company that owned and operated the Titan, is based in Everett, Wash., but the submersible was registered in the Bahamas. The Polar Prince, the vessel that launched the Titan, is from Canada, and the people on board the submersible were from England, Pakistan, France and the U.S.

A government official familiar with the investigation, but not authorized to discuss it, said Canada was likely to take a leading role.

The Coast Guard declined to comment.

Times staff writers Noah Goldberg and Jonah Valdez in Los Angeles contributed to this story. The Associated Press also contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.