Making Turkey great again: How Erdogan rode to reelection on a nationalist wave

- Share via

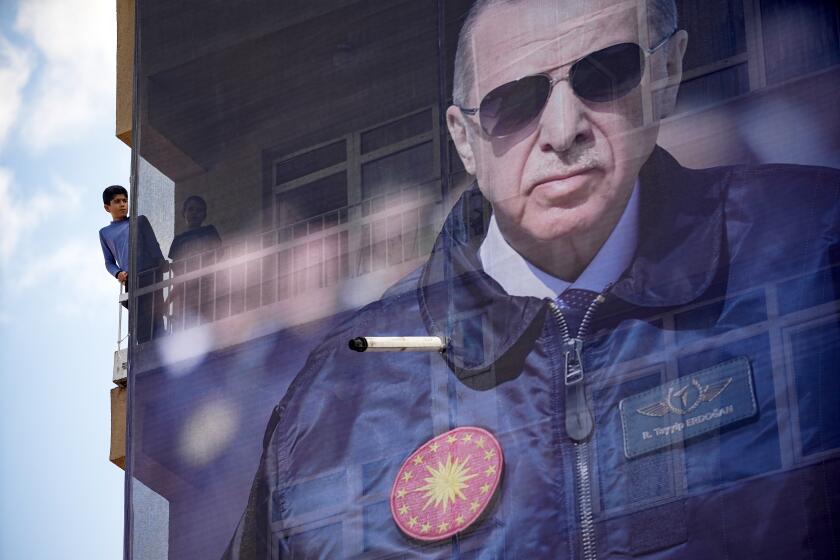

ISTANBUL — Before Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan snatched victory in the hardest fight of his two decades in power, a ubiquitous campaign poster showed him in dark sunglasses and a black aviator jacket with military patches alongside images of drones, ships, tanks and a ghostly national flag.

“He won’t leave the homeland unprotected,” the poster’s slogan said. “Go with the right man.”

It’s a martial persona that has come to occupy an ever-larger part of the political identity Erdogan has constructed over the last 20 years as Turkey’s president or prime minister. To an already-potent cocktail of Islamist and neo-liberal elements, Erdogan — who will be sworn in for a historic third presidential term Saturday — has added a large measure of muscular nationalism, which he channeled into a masterful, nostalgia-filled campaign that won him reelection and set him up to realize the vision he calls “Turkey’s Century.”

That vision taps not only into the country’s 100-year-old history as a secular republic but also into a honey-dipped view of its Ottoman Empire past. In Erdogan’s telling, the next 100 years will see Turkey restored to its former glory as a mighty actor on the world stage, an unabashedly Muslim military power capable of standing up to its adversaries and inspiring oppressed nations around the world.

In short: Make Turkey great again.

“Nations that were once great powers have a malleable and inflatable sense of their heyday,” said Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “With this comes an inclination to be inspired by leaders who can speak to this narrative and embody it, and that’s Erdogan in Turkey.”

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has courted Russia, to U.S. chagrin, while serving as a stalwart in the Western NATO alliance.

Erdogan, 69, has pledged to catapult Turkey, a NATO member with the alliance’s second-largest army, into the world’s top 10 nations in “all fields of politics, economy, technology, military and diplomacy.” It’s an all-out development drive involving energy independence, gargantuan — and controversial — infrastructure projects like the Kanal Istanbul, an artificial waterway to reduce traffic in the Bosporus, and, crucially, a homegrown weapons industry to make Turkey militarily stronger.

The last point is a particularly sore one: In 2019, the U.S. expelled Turkey from its fifth-generation F-35 fighter jet program after Erdogan’s government bought missiles from Russia. More recently, his refusal to accept Sweden into NATO over what he says is its harboring of Kurdish militants led Congress to block sales of F-16 fighter jets.

During his reelection campaign, he inaugurated the country’s first aircraft carrier, which was designed for the F-35 program but will instead deploy Turkish drones and helicopters. He also touted Turkey’s first tank and electric car as achievements that would propel the country into the next century.

Behind the displays of military power, said Asli Aydintasbas, a Turkish policy expert and visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, is Erdogan’s recognition of a rising tide of nationalism in the country.

“The trend is pointing to nationalism as the dominant force in Turkish society” — a force that cuts across both Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, and the opposition groups ranged against him, Aydintasbas said.

Ahead of the election’s May 14 first round, the increasingly authoritarian Erdogan — at last — seemed vulnerable. His early years in power had seen unprecedented economic growth. His government funded vast infrastructure projects — airports, bridges, elaborate mosques — that helped lift people into the middle class and propelled the country of 85 million into the world’s 20 top economies.

Polls show Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan facing the toughest reelection race of his career as the country prepares for an election Sunday.

But the Turkish lira’s value plunged in 2018, and Erdogan’s stubborn refusal to raise interest rates saw inflation skyrocket to 80% before settling down to a little more than half that this year; in cities, it remains in the triple digits. His government’s lackluster rescue efforts in February’s disastrous earthquakes — which killed at least 50,000 people and left millions homeless — enraged many.

Polls predicted his quick defeat to a coalition of six opposition parties that had united to defeat him. Instead, he led in a nail-biting first round before defeating challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu in an unprecedented runoff election Sunday with 52% of the vote.

To be sure, some credit for that victory goes to Erdogan’s control of the media and his use of state levers — raising the minimum wage and pensions, offering free gas — to win votes. International monitors judged the election to be free but not fair.

But he also hammered home a message that cast him as Turkey’s primary protector and the only one who could restore it to its Ottoman grandeur.

The election battle between Turkey’s president and his main challenger is increasingly focused on one issue: Syrian refugees in their country.

His vision of Turkey’s Century “draws its inspiration from the thousand-year-old glorious past of our ancestors” as well as the modern republic, he said in a speech late last year. Erdogan named himself in the line of succession of important Turkish rulers, including, most notably, Osman Bey, the Ottoman Empire’s founder, and Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the republic.

“Let’s transform our country into a locomotive instead of a cog in the global wheel,” he said.

Throughout his campaign, Erdogan railed against a host of enemies, both within and without, who have “hindered [Turkey’s] enormous potential”: secularists; segments of the Kurdish minority; activists, writers and scholars who disagree with his politics; the LGBTQ+ community.

“The fear of those who suffocate us … is that Turkey’s Century, of which we are giving the good news today, will one day come to their doorstep,” Erdogan said in a victory speech to his supporters after the election. “All the traps set in front of Turkey for the last 10 years, all the games played on it, all the daggers in its back, all the trips in its feet are to prevent today. … This is that day. You are here for it.”

The rhetoric echoes that of other leaders who have ridden similar waves of nationalism and nostalgia, such as former President Trump with his MAGA promises, former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Brexit cheerleading, and President Vladimir Putin’s revanchism in Russia.

“You have this conception of a golden past and you’re trying to retrieve it. You have a community you blame for having robbed you of this golden past, and you organize your politics in opposition to them,” said Selim Koru, a Turkey-based political analyst.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It also promotes a paranoid view of the opposition, under which Erdogan’s supporters need to be constantly vigilant for any sign of his enemies conniving against him.

“The idea is always that history is derailed from its original path in which you’re the good guys — you’re supposed to win — but the bad guys have won, and you need to reverse things,” Koru said.

In a challenge for Washington and Europe, the list of antagonists increasingly includes the West.

Two days before the runoff, Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu, an Erdogan ally, said that after the election, “whoever pursues a pro-American policy in Turkey will be labeled a traitor.”

Much like Los Angeles, Istanbul is facing a double crisis — a severe housing shortage and extreme earthquake risk — leaving residents in a bind.

During his victory speech, Erdogan gloated that “German, French and English magazines published covers to bring down Erdogan? They also lost.”

With so much talk of adversaries, whether real or imagined, Erdogan is shifting Turkey’s traditional stance on the geopolitical stage, said Aydintasbas of the Brookings Institution.

“That’s possibly Erdogan’s legacy: He has rebranded Turkey as a rising, nonaligned power — a power that has no friends but only enemies,” she said.

Beyond military prowess, Erdogan’s vision encompasses a new constitution and social changes, such as enshrining women’s right to wear headscarves — a central issue for many conservatives in the country — and protecting the “family institution from the threat of deviant currents.”

The suspect, identified only by his code name Husam, was apprehended in the Syrian city of Azaz, a Turkish-controlled area in northwestern Syria.

Erdogan’s promise of Turkish exceptionalism strikes a chord with voters like Ali Ozman, a 63-year-old mechanic from Istanbul who has been a devotee of Erdogan’s since he began his political career as the city’s mayor in 1994.

“The other side doesn’t have a project like he does, no plan that they share with people,” said Ozman, who spoke rhapsodically of all the improvements — clearing away trash, building roads and hospitals — he attributes to Erdogan. “I feel safe, and that the path for our youth is open now.”

In the end, Erdogan’s rosy view of the country’s future resonated with voters more than the opposition’s focus on his missteps, said Harun Kucuk, a director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Middle East Center.

“The opposition said all these problems were Erdogan’s making; they were a doctor curing a sickness, whereas Erdogan doesn’t do that,” he said.

“I don’t know how much of Erdogan’s constituency are ideologically well informed. But he does make them feel good about the future.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.