In Belarus, anti-Russia guerrillas sabotage railways, attack warplane to help Ukraine

- Share via

After Russia invaded Ukraine, guerrillas inside Belarus began carrying out acts of sabotage on their country’s railways, including blowing up track equipment to paralyze the rails that Russian forces used to get troops and weapons into Ukraine.

In the most recent sabotage to make international headlines, they attacked a Russian warplane parked just outside the Belarusian capital, Minsk.

“Belarusians will not allow the Russians to freely use our territory for the war with Ukraine, and we want to force them to leave,” Anton, a retired Belarusian serviceman who joined a group of saboteurs, told the Associated Press in a phone interview.

“The Russians must understand on whose side the Belarusians are actually fighting,” he said, speaking on the condition that his last name be withheld for security reasons.

More than a year after Russia used the territory of its neighbor and ally to invade Ukraine, Belarus continues to host Russian troops, as well as warplanes, missiles and other weapons. The Belarusian opposition condemns the cooperation, and a guerrilla movement sprang up to disrupt the Kremlin’s operations, both on the ground and online. Meanwhile, Belarus’ authoritarian government is trying to crack down on saboteurs with threats of the death penalty and long prison terms.

Activists say the rail attacks have forced the Russian military to abandon the use of trains to send troops and materiel to Ukraine.

Multiple drones target Kyiv in an overnight attack only three days after what Ukraine described as one of Russia’s biggest assaults on the capital.

The retired serviceman is a member of the Assn. of Security Forces of Belarus, or BYPOL, a guerrilla group founded amid mass political protests in Belarus in 2020. Its core is composed of former military members.

During the first year of the war, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko realized that getting involved in the conflict “will cost him a lot and will ignite dangerous processes inside Belarus,” said Anton Matolka, coordinator of the Belarusian military monitoring group Belaruski Hajun.

Last month, BYPOL claimed responsibility for a drone attack on a Russian warplane stationed near Minsk. The group said it used two armed drones to damage the Beriev A-50 parked at the Machulishchy Air Base. Belarusian authorities have said they requested the early-warning aircraft to monitor their border.

Lukashenko acknowledged the attack a week later, saying that the damage to the plane was insignificant but admitting that it had to be sent to Russia for repairs.

On the Belarusian border, Ukrainian drones monitor a long expanse of marsh and woodland for a possible Russian offensive from the north.

Lukashenko also said that the perpetrator of the attack was arrested along with more than 20 accomplices and that he had ties to Ukrainian security services.

Both BYPOL and Ukrainian authorities rejected allegations that Kyiv was involved. BYPOL leader Aliaksandr Azarau said the people who carried out the assault were able to leave Belarus safely.

“We are not familiar with the person Lukashenko talked about,” he said.

The attack on the plane, which Azarau said was used to help Russia locate Ukrainian air-defense systems, was “an attempt to blind Russian military aviation in Belarus.”

Ales Bialiatski and three other human rights advocates are convicted of financing actions violating public order and smuggling in Belarus.

He said the group is preparing other operations to free Belarus “from the Russian occupation” and to free Belarus from Lukashenko’s regime.

“We have a two-headed enemy these days,” said Azarau, who remains outside Belarus.

Former military officers in the BYPOL group work closely with the team of Belarus’ exiled opposition leader, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who ran against Lukashenko in the 2020 presidential election, which was widely seen as rigged.

The disputed vote results handed him his sixth term in office and triggered the largest protests in the country’s history. In response, Lukashenko unleashed a brutal crackdown on demonstrators, accusing the opposition of plotting to overthrow the government. Tsikhanouskaya fled to Lithuania under pressure.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

With the protests still simmering a year after the election, BYPOL created an underground network of anti-government activists dubbed Peramoha, or Victory. According to Azarau, the network has some 200,000 participants, two-thirds of them in Belarus.

“Lukashenko has something to be afraid of,” Azarau said.

Belarusian guerrillas say they have already carried out 17 major acts of sabotage on railways. The first took place just two days after Russian troops rolled into Ukraine.

A month later, then-Ukrainian railways head Oleksandr Kamyshin said there “was no longer any railway traffic between Ukraine and Belarus,” and thanked Belarusian guerrillas for it.

A Belarus court sentences exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who lives in Lithuania, to 15 years in prison after a trial in absentia.

Another group of guerrillas operates in cyberspace. Their coordinator, Yuliana Shemetovets, said some 70 Belarusian IT specialists are hacking into Russian government databases and attacking websites of Russian and Belarusian state institutions.

“The future of Belarus depends directly on the military success of Ukraine,” Shemetovets said. “We’re trying to contribute to Ukraine’s victory as best we can.”

Last month, the cyber-guerrillas reported hacking a subsidiary of Russia’s state media watchdog, Roskomnadzor. They said they were able to penetrate the subsidiary’s inner network, download more than two terabytes of documents and emails, and share data showing how Russian authorities censor information about the war in Ukraine.

They also hacked into Belarus’ state database containing information about border crossings and are now preparing a report on Ukrainian citizens who were recruited by Russia and went to meet with their handlers in Belarus.

Kherson, the provincial capital occupied by Russia, is back in Ukrainian hands. But its people face privation, along with neighbor-against-neighbor suspicions.

In addition, the cyber-guerrillas help vet Belarusians who volunteer to join the Kastus Kalinouski regiment that fights alongside Kyiv’s forces. Shemetovets said they were able to identify four security operatives among the applicants.

Belarusian authorities have unleashed a crackdown on guerrillas.

Last May, Lukashenko signed off on introducing the death penalty for attempted terrorist acts. Last month, the Belarusian parliament also adopted the death penalty as punishment for high treason. Lukashenko signed the measure Thursday.

“Belarusian authorities are seriously scared by the scale of the guerrilla movement inside the country and don’t know what to do with it, so they chose harsh repressions, intimidation and fear as the main tool,” said Pavel Sapelka of the Viasna human rights group.

Human rights activists say Belarus is sewing yellow tags on political prisoners’ clothes to single them out, in a move with echoes of Nazi Germany.

Dozens have been arrested, while many others have fled the country.

Siarhei Vaitsekhovich runs a Telegram blog where he regularly posts about Russian drills in Belarus and the deployment of Russian military equipment and troops to the country. He had to leave Belarus after authorities began investigating him on charges of treason and forming an extremist group.

Vaitsekhovich said his 15-year-old brother was recently detained in an effort to pressure him to take the blog down and cooperate with the security services.

The Russian Federal Security Service “is very unhappy with the fact that information about movements of Russian military equipment spills out into public domain,” Vaitsekhovich said.

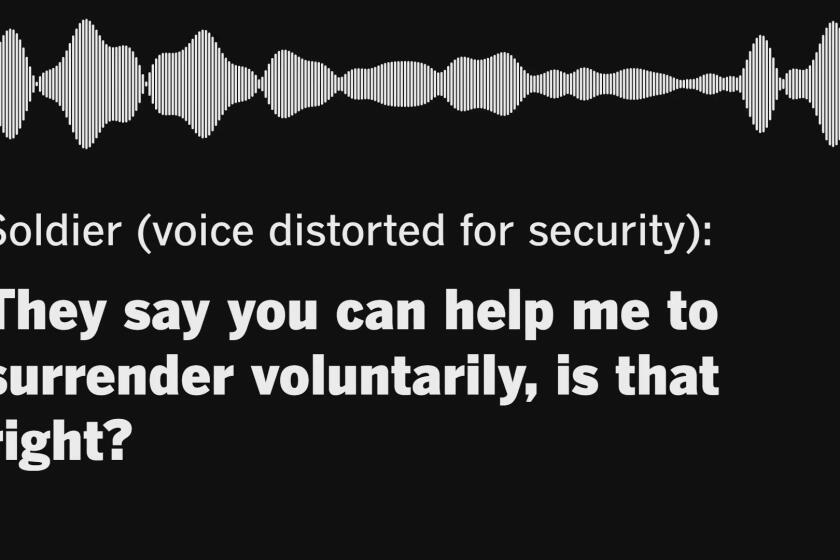

Ukraine’s “I Want to Live” hotline instructs Russian soldiers on how to surrender.

According to Viasna, over the last 12 months at least 1,575 Belarusians have been detained for their anti-war stance, and 56 have been convicted of various charges and sentenced to prison terms ranging from a year to 23 years.

Anton says he understands the risks. On one of the railway attacks, he worked with three associates who were each sentenced in November to more than 20 years in prison.

“It is hard to say who is in a more difficult position — a Ukrainian in a trench or a Belarusian on a stakeout,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.