Cubans respond with zeal to new U.S. migration policy

- Share via

HAVANA — In barely a week, 25-year-old engineer Marcos Marzo went from riding his small electric motorcycle past the low buildings of Havana’s Vedado district to traveling the mega-highways of Florida, amazed by the towering high-rises and giant supermarkets.

A close relative told Marzo on Jan. 21 that he had applied online to sponsor the young engineer’s trip to Florida as required by the new parole program for Cuban migrants set up by the Biden administration. The next day the sponsorship had been confirmed and the day after that it was approved.

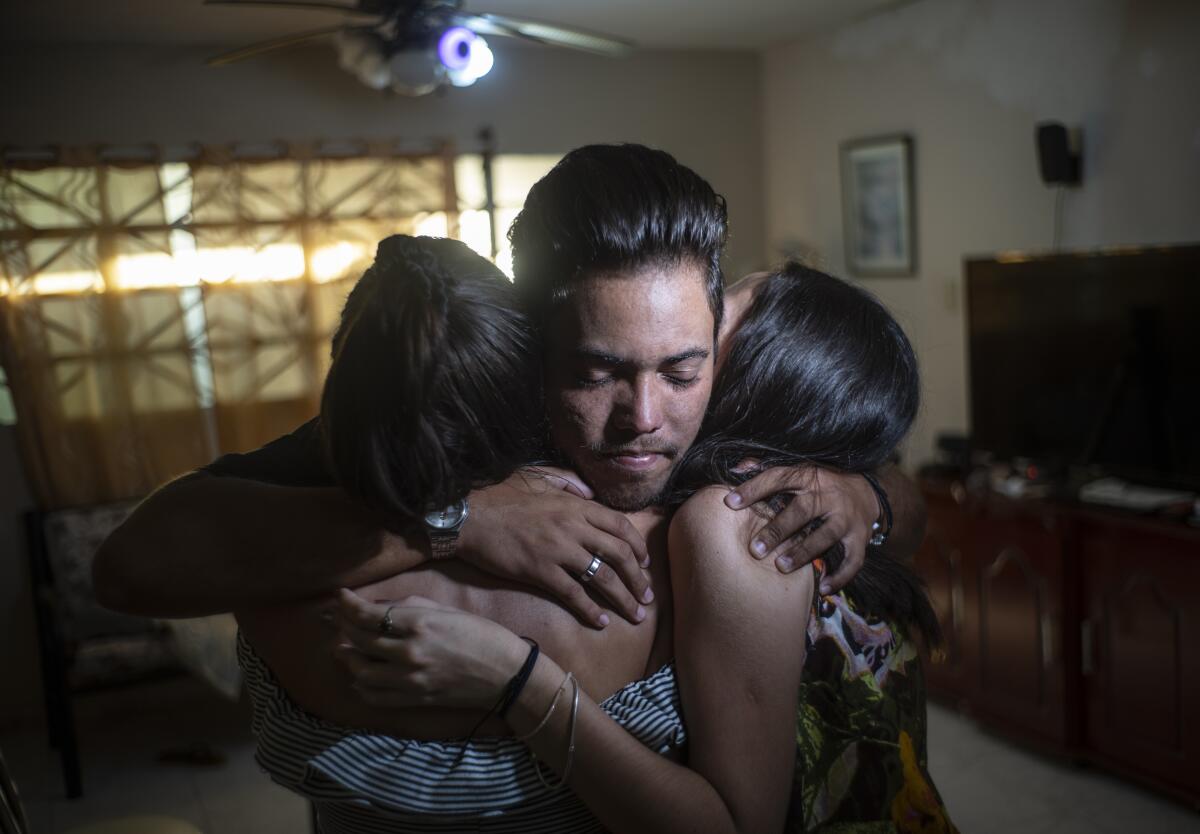

With his printed authorization in hand and a small blue suitcase, Marzo climbed aboard a plane to Hialeah, Fla., last Friday, shaken by the speed of it all.

“It has been very hard, that in seven days your life changes so drastically, it fills you with hope, but at the same time, it fills you with dread,” Marzo told the Associated Press before leaving for what he knew would be a personal watershed.

One California water manager says Colorado River reservoirs aren’t likely to refill. Scientists agree that the region needs to plan for a drier future.

Overwhelmed by thousands of Cubans crowding its southern border after making the dangerous trip through Central America and an increase in makeshift boats crossing the Florida Straits, the United States in early January approved a policy change that makes migrants request a permit, or parole, online before arriving with the sponsorship of a relative or acquaintance in the U.S.

Cubans, who qualify for the program along with Nicaraguans, Haitians and Venezuelans, have responded with zeal, launching a search for sponsors and long lines to obtain documents. The program’s backers hope it will help would-be migrants avoid the risks of the route through Mexico — plagued by traffickers — and bring order to the migrant flow.

“This option has come like a light,” said Marzo, who had been living with his parents in Havana. Now in the U.S., his dream is to complete a master’s degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and work as an engineer, which he says is his passion.

According to figures from U.S. border authorities, in the 2021-22 fiscal year — which began in October 2021 and ended in September — officials had a record 224,000 encounters with Cuban migrants on the Mexican border. In October 2022, there were 29,878 Cuban migrants stopped, in November 35,881 and in December 44,064.

Meanwhile, the Coast Guard intercepted 6,182 Cubans trying to arrive by sea in fiscal year 2021-22. Add to that 4,795 in the last three months.

All the figures are records and come amid serious economic crises on the island caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, inefficiencies in economic reforms and a radical tightening of U.S. sanctions, which seek to pressure the Cuban government to change its model. Blackouts, shortages, inflation, long fuel lines and dollarization marked parts of 2021 and 2022 in Cuba, while the country saw its first street demonstrations in decades with thousands of people demanding an end to the power outages.

Until Jan. 5, Cubans who arrived at the northern border of Mexico obtained permits that granted them entry into U.S. territory, assuming there was a credible fear that prevented them from returning to the island. Later they usually ended up with refugee benefits, and a year after that, the protection of the Cuban Adjustment Act.

Then the Biden administration unveiled its new policy: 30,000 migrants will be accepted each month from Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Haiti. The migrants can stay for up to two years but must have a sponsor already in place in the United States. Those who risk reaching the borders without permission would be deported and not able to enter U.S. territory for five years.

There are still questions about the program, including how many people from each of the four countries will be accepted.

And the program is not without controversy in Cuba amid the migrant boom in recent months, since many people had already begun their journeys toward the United States on the previous route. Some had even sold houses and cars to make the journey through Central America, which begins with a flight to Nicaragua and continues up through Mexico to the U.S. border. It is a route plagued by dangers and human traffickers.

Yudith Cardozo, a 46-year-old homemaker, said the new parole program is “a unique opportunity” that could save lives.

“Nicaragua is a total risk. Mexico, all that journey is a total risk,” she said.

Marzo acknowledged that he had considered migrating by the route of “the volcanoes,” as Cubans popularly call the Central American journey, but his parents talked him out of it. The number of people who have died on the journey is unknown.

Cardozo, speaking while waiting in front of a government office to obtain birth certificates and a criminal record certificate, said a relative in the U.S. had initiated the process as sponsor for her, her 16-year-old son and her husband, but in three weeks they had gotten no response.

Many Cubans wanting to migrate cannot apply for the program because they lack a sponsor in the U.S.

On social media, memes have spread rapidly about Cubans rediscovering distant cousins or previously unknown uncles in the United States, and the U.S. Embassy warned Cubans to be careful to avoid fraud and even human trafficking.

Meanwhile, Cubans are crowding public offices to request passports and other documents, in some cases forming lines before dawn. The AP found that the postage stamps needed for the process have become scarce.

Some experts defend the program but acknowledge that without an upturn in the Cuban economy, it is unlikely to reduce the record number of departures.

Biden’s widespread use of humanitarian parole has been criticized forcefully by advocates for more restrictive immigration policies, including Stephen Miller, a former senior advisor to former President Trump. Texas and 19 other Republican-led states have sued to halt the policy, arguing it is effectively an amnesty for 360,000 people a year. Many on the left welcome the policy but caution that it cannot be used as a substitute for asylum.

The parole program “will help to a certain extent to make Cuban migration safer, more orderly and legal,” said William LeoGrande, a political scientist at the American University in Washington, D.C. “But the number of Cubans trying to come to the United States right now is so huge that the parole program is not big enough to meet the demand.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.