‘Election denial is alive and well’: Despite statewide losses, conspiracists win some local offices

- Share via

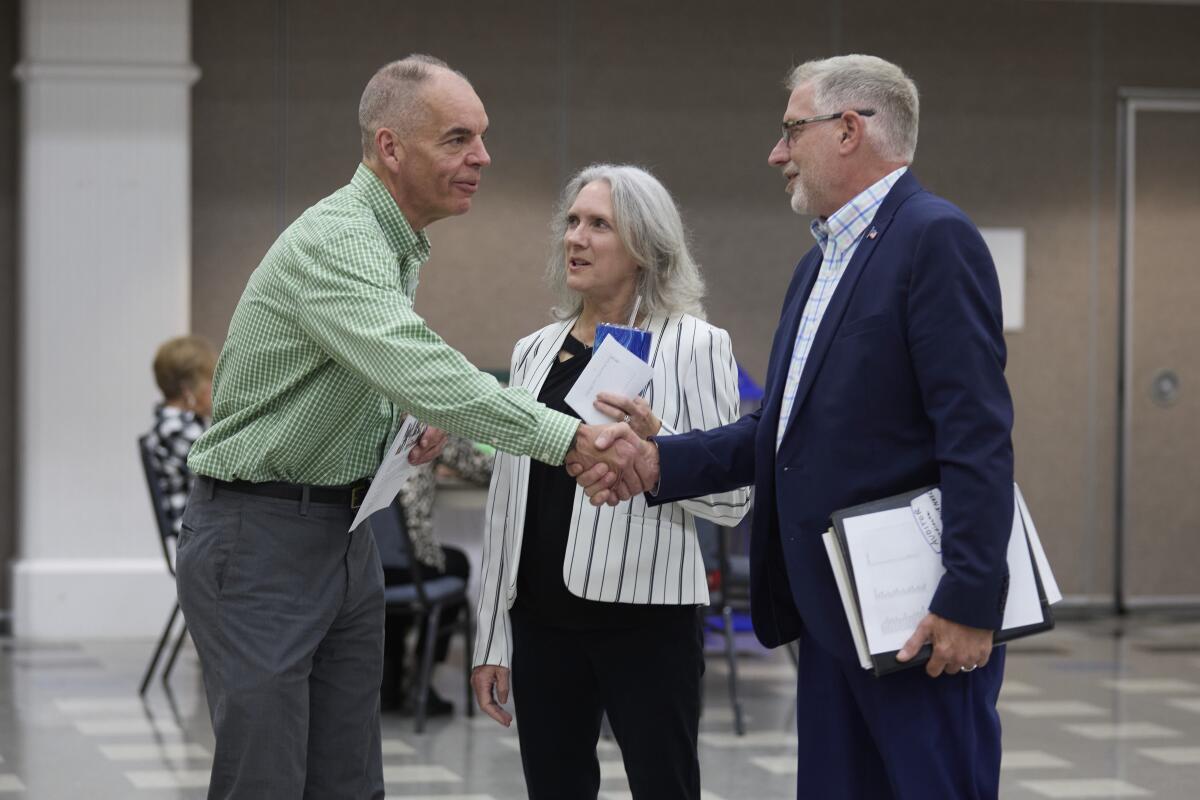

As voting experts were cheering the losses of election conspiracy theorists in high-profile races, Paddy McGuire was preparing to hand over his office to one of them.

McGuire, the auditor of Mason County in western Washington, lost his reelection bid to Steve Duenkel, a Republican who has echoed former President Trump’s lies about the 2020 election. Duenkel, who invited a prominent election conspiracist to the area and led a door-to-door effort to hunt for voter fraud, defeated McGuire by 100 votes in the conservative-leaning county of 60,000.

“There are all these stories about the election denier secretary of state candidates who lost in purple states,” said McGuire, referring to the office that normally oversees voting. “But secretaries of state don’t count ballots. Those of us on the ground, whether we’re clerks or auditors or recorders, do.”

Republicans who supported Trump’s lies lost bids for offices that help oversee voting in the six states that decided the last presidential election, as well as in races across the country. But some won races to control local positions that run on-the-ground election operations in counties, cities and townships.

“Without a doubt, election denial is alive and well, and this is a continuing threat,” said Joanna Lydgate of States United, a group that highlights the risk of conspiracy theorists trying to take over election administration.

Donald Trump is an insurrection-inciting former president who wants his job back. Readers say prominently covering him plays into his hands.

Of the nine Republicans running for secretary of state who echoed Trump’s lies about 2020 or supported his efforts to overturn its results, three won — all in Republican-dominated states.

In Alabama, state Rep. Wes Allen hasn’t waited to take office before making waves. He announced that once he becomes secretary of state, he will withdraw from ERIC, a multistate database of voter registrations. The system, designed to notify states when voters need to be removed from electoral rolls because they’ve relocated, has become a target of conspiracy theorists.

Allen echoed those conspiracy theories during his campaign but in a statement since said he was motivated by a desire to protect the privacy of Alabama voters. His call to exit ERIC drew a rebuke from the outgoing secretary of state, John Merrill, a fellow Republican.

“So, if Wes Allen plans to remove Alabama from its relationship with ERIC, how does he intend to maintain election security without access to the necessary data, legal authority or capability to conduct proper voter list maintenance?” Merrill’s office said in a statement.

In conservative Wyoming, Chuck Gray was the only candidate for secretary of state; after he won the GOP primary in August, his ascension was guaranteed.

In Indiana, Diego Morales ousted the incumbent secretary of state, a fellow Republican, during the party’s nominating convention by echoing Trump’s lies about 2020. He reined in his rhetoric during his successful general election campaign.

Morales did not respond to a request for comment. He was the only one of 17 Republican election conspiracists in a group called the America First Secretary of State Coalition to win his general election.

The record is far murkier at the local level, where ballots are counted. There are thousands of election offices in the U.S. In many states, elections are conducted by county offices overseen by clerks or auditors, though in some they are administered at the municipal level in cities or townships.

No organization tracks local election offices. The Democratic group Run for Something, alarmed at the prospect of election deniers occupying these posts, this year started an initiative to support candidates it dubbed “defenders of democracy.” It estimated that 1,700 races were being held for posts to run elections or for bodies such as county commissions that appoint election directors.

Co-founder Amanda Litman said Run for Something was tracking 32 races in which it supported candidates. The group’s candidates won in 17 races and lost in 12; three have yet to be called. Most significant, she said, the group’s candidates won eight races against election deniers and lost three.

“It’s generally a good sign that when you’re able to make the stakes of the race about democracy, you win,” Litman said.

Still, she added, it’s hard to track all the election deniers who got into local office: “It’s a little bit unknowable.”

Some prominent election deniers did win local posts.

In the Atlanta area, Bridget Thorne, who attended meetings of the Fulton County Commission to talk about conspiracy theories around the 2020 election, won a post on the commission. However, it’s dominated by Democrats, so she is likely to have limited ability to bring pressure on the county elections department.

In Washoe County, the swing area in Nevada that includes Reno, Republican Mike Clark won one of five county commission seats. He told a local newspaper, “I don’t have any personal knowledge” of whether President Biden legitimately won the 2020 election.

In Washington’s Mason County, Duenkel spread conspiracy theories about local and national elections. He helped a group of volunteers who went door-to-door checking for voters who didn’t live where they were registered and claimed they found thousands. A local television station retraced the group’s steps and found that it had made numerous errors.

Still, every Republican on the ballot in Mason County won. McGuire said he left Duenkel a voicemail to congratulate him but never got a call back. Duenkel also did not respond to requests for comment from the Associated Press.

“He got more votes than me, and he won,” McGuire said. “That’s what an election professional does — respect the will of the voters and stand behind the results, whether one is happy about the outcome or not.”

___

Associated Press coverage of democracy receives support from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.