- Share via

UMÁN, Mexico — Leer en español

Shortly after being found at a high school on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, the body of a newborn arrived at the medical examiner’s office.

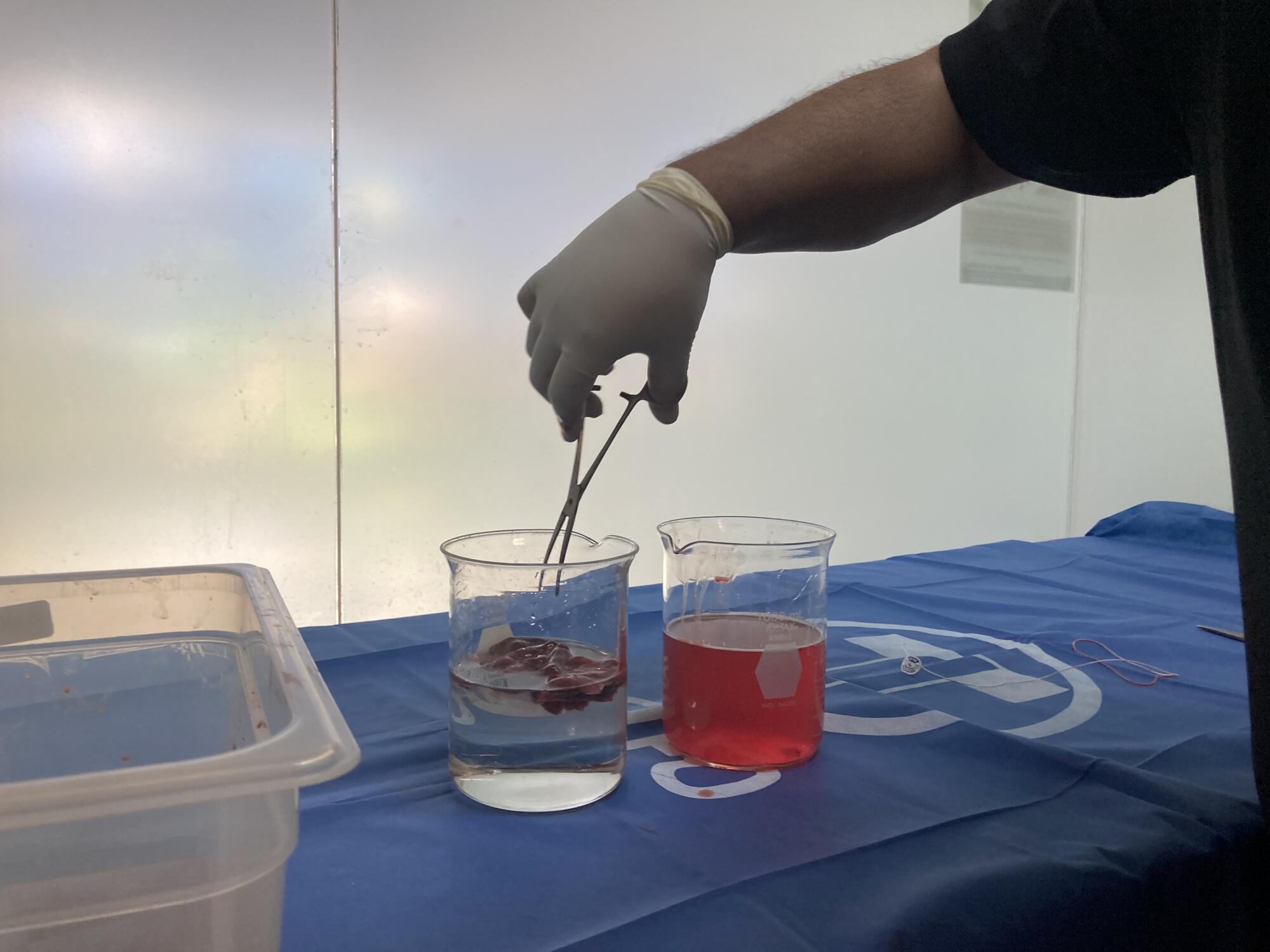

The autopsy team placed the boy on a scale — which indicated 5 pounds, 4 ounces — and searched for clues to how he died. Opening his chest, they removed a tiny pair of reddish lungs and set them in a container of water.

It was a key moment and a test. If the lungs floated, they presumably contained air, which would suggest the infant took a breath when he entered the world. If the lungs sank, it would point to a stillbirth.

The lungs floated. And when they were pushed underwater, bubbles appeared.

“The fetus breathed the moment it was born,” the medical examiner wrote in her report — a finding that opened the door for prosecutors to file murder charges against a teenager named Guadalupe.

The flotation test, as it is known, dates to at least the 1600s, and today it is standard practice in many parts of Latin America. The Times reviewed six cases in Mexico, El Salvador and Argentina in which prosecutors relied on it to charge women with homicide. Some were sentenced to decades in prison.

Desde México hasta Argentina, los fiscales se han basado en la prueba docimasia hidrostática para condenar a las mujeres por matar a sus bebés.

In the world of forensics and criminal investigation, the flotation test stands out for its simplicity.

There is only one problem: It can easily be wrong.

Air and other gases can enter the lungs of a stillborn baby multiple ways — as the fetus is squeezed through the birth canal, during resuscitation attempts, during decomposition, even through ordinary handling of the body. When that happens, the lungs may float, even though the baby never took a breath.

In rare instances, courts in Latin America have recognized the dangers of relying on the flotation test. But that has not translated to broader changes in how it is used.

Dr. Gregory Davis, a forensic pathologist at the University of Kentucky who has studied the test, said in many of the deaths the truth can never be known.

“It’s an invalid test that has gained a veneer of reliability,” he said.

::

There are few statistics on how many women in Latin America have been prosecuted for killing their newborns. Public records requests by activists in Mexico suggest that there are at least three convictions a year.

Even less studied is how often the flotation test is a decisive piece of evidence in such cases.

In El Salvador, Jocelyn Viterna, a Harvard sociologist who studies reproductive rights, reviewed 59 cases of women charged with killing their newborns between 1998 and 2017. At least 38 of them were convicted.

She said that the flotation test was used routinely and that in her conversations with Salvadoran prosecutors they referred to it as the “gold standard.” The director of the country’s forensics institute declined a request for an interview.

The surge in such prosecutions in El Salvador, which began in the late 1990s, grew out of a militant antiabortion movement, Viterna said, and has been driven not by evidence but rather a widespread belief among authorities that the women wanted to escape the responsibilities of motherhood.

“Despite the diversity of situations, overwhelmingly they arrest the women and give the exact same story about why the woman is guilty,” she said.

In Viterna’s view, nearly all are innocent.

Many of the accused women are poor and delivered at home, often alone, and maintain they didn’t know they were pregnant, which some prosecutors find unbelievable.

While it is rare for women to deliver without realizing they are pregnant, experts say that obesity, irregular menstrual cycles and ignorance about sex make it more likely. In a 2002 study of births in the Berlin area, German researchers found it happened in roughly 1 out of every 2,500.

Moreover, lack of medical care increases the risk for complications during labor and stillbirth, but prosecutors have rarely recognized that when filing murder charges.

Guadalupe is the child of divorced parents and one of three siblings, and she grew up poor in Umán, a municipality of 70,000 near Mérida, the capital of Yucatan state. She spoke on the condition that she be identified by only her middle name.

Though she had been sexually active and noticed she’d been gaining weight, she said, she had no idea she was pregnant one October morning in 2019, when she rushed to a bathroom at her school with stomach pains.

In her telling, she heard a thunk as her son hit the toilet. He did not cry or even move. She needed to put him somewhere, and in her panic, the trash bin next to the stall seemed like the best option. Then she fainted.

“I didn’t know how to react,” said Guadalupe, who was 17 at the time. “I was in shock.”

Staff at the school as well as Guadalupe’s father, grandmother and brother told authorities that they hadn’t known that she was pregnant — statements that prosecutors used to bolster their case that she had secretly plotted to kill her son and had thrown him in the trash “as if it were an object without value.”

While the medical examiner, Dr. Diana Carolina Balam Xool, relied on the flotation test to rule out a stillbirth, she concluded from a tiny cut and bruise on the boy’s lower lip that he had been smothered.

Dr. Lee Marie Tormos, a medical examiner in Palm Beach County, Fla., who reviewed the case for The Times, said the bruise could have occurred during a traumatic birth and “in and of itself does not explain a dead baby.”

As for the fact that the lungs floated, she said that alone shed little light on whether the baby was born alive.

::

Some historians credit the Roman Empire-era physician Galen with the concept behind the flotation test. Scientists have long warned that it is unreliable.

After Dr. Theodric Beck — who wrote the first major U.S. book on forensic medicine in 1823 — found in an experiment that the lungs of a stillborn baby floated, he concluded that “mere floating is no proof that the child was born alive.”

In the 2004 edition of the European classic “Knight’s Forensic Pathology,” the authors wrote that they were “saddened to contemplate the number of innocent women who were sent to the gallows in previous centuries on the testimony of doctors who had an uncritical faith in this crude technique.”

And in a 2020 letter solicited by the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, a nonprofit based in New York that has helped defend U.S. women accused of killing their newborns, 25 forensic scientists wrote that the flotation test is “not a scientifically reliable test or indicator of live birth.”

Figuring out whether a baby was born alive is a complicated endeavor that experts say should involve a host of tests, including an examination of the lungs under a microscope to see whether the air sacs are uniformly dilated. X-rays can also be useful for showing whether air is evenly distributed in the lungs.

The medical examiner in Guadalupe’s case did not mention either test in her autopsy report or in her statement to prosecutors. She told them she based her conclusion on the flotation test and a visual inspection of the lungs. Neither her office nor the prosecutors responded to requests for comment.

Still, research has found that for births in hospitals — where it is known how the body was handled and there is no evidence of decomposition — the flotation test can be valid. That has led some experts to say it can be helpful when used in conjunction with other techniques.

“There are mistakes made, absolutely, and there are innocent people in jail because of that, but it can sometimes be very useful,” said Dr. Michael Baden, a former chief medical examiner of New York City. “When making a diagnosis, usually a doctor doesn’t rely on one thing.”

Davis, the University of Kentucky pathologist, has questioned that logic.

“If you don’t rely on it, why do you use it?” he said. “Talk about a chain of failures that ultimately leads to a plane crash.”

In Latin America, senior experts such as Dr. Fernando Octavio Flores Reyes, president of the forensic medicine association in Mexico, understand the pitfalls. But some medical examiners’ offices lack more expensive technology.

“Many times my colleagues have to resort to the test that’s most used, which is the flotation test,” he said.

::

Courts in multiple countries have exonerated women after determining that too much weight had been given to the flotation test.

One of those women was Maria del Carmen Viera, who was 26 and already raising four children on her own when she gave birth at home in the countryside of Argentina’s Corrientes province in 1999. She testified that her son was silent and motionless and that hours later she reported the death to staff at a hospital.

She then held a wake before burying the baby inside a henhouse.

A 17-year-old neighbor who saw her alerted authorities, who arrived at Viera’s home and unearthed a box containing the newborn.

The medical examiner cited the flotation test, inflated lungs and a finding of gas in the stomach to conclude that the baby had been born alive and — based on a fractured bone in the neck — determined that the cause of death was strangulation. The examiner wanted to study the lungs and neck under a microscope, but a superior said the instruments weren’t available and denied the request.

A court sentenced Viera to life in prison.

She might have died there, but a few years later an official with the public defender’s office met her in prison and was struck by her insistence that she was innocent.

The official sent the autopsy to be reviewed by a team of forensic experts, who determined that the strangulation finding was “unfounded and reckless” and that too much weight had been given to the flotation test.

Based on that review, a higher court ruled in 2013 that there had been no proof the infant had been born alive and ordered Viera released.

In 2019, she and her family were awarded about $45,000 in reparations for the 13 years she spent in prison.

In a different case, a court in El Salvador sentenced Maria Teresa Rivera to 40 years in prison for killing her newborn in 2011 by throwing him into a pit latrine.

Rivera, who was 28 at the time and had been living near the capital, San Salvador, and working in a garment factory, said she had no idea she was pregnant and had simply woken up in pain and gone to the latrine.

“I felt something come out,” she said. “When I cleaned myself, I was full of blood.”

Feeling dizzy, she headed to the bedroom she shared with her former partner’s mother. The last thing she remembers is the older woman finding her on the floor.

When Rivera gained consciousness, she was handcuffed to a hospital bed.

“They tell me I’m detained because I had killed my son,” she said. “I said I hadn’t killed anyone.”

A medical examiner performed a positive flotation test that afternoon. Though the autopsy found that the newborn had died from sudden complications during birth, the court concluded — with no evidence — that he had been asphyxiated from feces in the latrine.

“There’s no doubt that the baby was born alive,” the court said in its sentence, ruling that Rivera had to have known she was pregnant and wanted to get rid of the baby.

She spent the next four years in prison where other inmates called her a murderer.

Then in a 2016 appeal, two forensic experts and a pediatrician testified that the medical examiner had inappropriately relied on the flotation test.

The medical examiner himself testified that prosecutors hadn’t asked for a microscopic examination of the lungs because “they’re expensive, you can’t do it for everyone.”

The court ordered Rivera’s release, saying, “We can’t be irresponsible and limit the fundamental right of freedom with tests that are unreliable.”

Back in her hometown, Rivera struggled to find a job. People spat in her face when she went to the market. She was granted asylum in Sweden, where she now lives with a 17-year-old son and works as an aide in a nursing home.

She often thinks about how old her other child would have been had he lived.

“I still can’t get out of my head that maybe I could have done something,” she said.

::

Infants can die in the early minutes of life for a variety of reasons.

In the United States in 2019, just over 3,000 newborns survived less than an hour, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Experts say such deaths are almost certainly more common in countries with worse medical care.

“There are lots of things that can happen very suddenly during labor that put particularly the baby at risk,” said Joy Lawn, a neonatal death expert at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “You have to have a sense of urgency and be monitoring.”

In what academics and activists say reflects a zeal to prosecute, courts have often disregarded those possibilities.

That appears to have been the case after Isabel Hernandez Contreras gave birth at her home about an hour outside San Salvador in 2013.

Police responding to her call found Hernandez, then 18, bleeding on the street and later that day her infant dead in a pit next to her house. She was convicted of murder and began serving a 30-year prison sentence.

Based on the flotation test, the medical examiner had determined that the boy had breathed. But that wasn’t in dispute.

Hernandez said her baby was born alive but died soon after. She cut the umbilical cord with a knife.

“It breathed and at the same time looked like it was drowning, and I couldn’t do anything,” she said.

As for how he wound up in the pit, Hernandez called that “my big mistake.”

“I was worried that the police would think that I had killed my baby, so I hid him,” she said. “I hid him, but I wasn’t thinking clearly.”

The medical examiner concluded that the cause of death was asphyxiation “from material in the pit.”

Fausto Rodriguez, a pathologist at UCLA who reviewed the autopsy for The Times, said he saw no evidence for that determination. Calling the autopsy “very poorly done,” he faulted the medical examiner for failing to examine the lungs with a microscope or look for genetic anomalies that could explain a natural death.

Hernandez spent nearly nine years behind bars.

She was released in January after the president’s office commuted her sentence, which the country’s Supreme Court said had been handed down during a trend of escalating punishments for women who “don’t comply with the social role of being a mother that’s been assigned to them in a patriarchal society.”

Hernandez is now back with her family and taking cosmetology classes.

“I would blame myself for not being able to save the baby,” she said. “It hurts me still, of course, because it was my first child.”

::

One case of alleged infanticide in Latin America has received more attention than any other: the prosecution of Manuela.

Her real name — Manuela is a pseudonym used in court documents — has never been made public. But her story has become a rallying cry for feminists.

In 2008, her mother found her unconscious in their home in a village in northeastern El Salvador. After doctors at a hospital determined she had delivered a baby, one of them alerted authorities, who found the decomposing body of her infant son in a septic tank.

She was convicted of murder and sentenced to 30 years in prison, where she died from cancer in 2010 at age 32.

Advocacy groups continued to pursue her case, which eventually reached the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Among the evidence it considered was expert testimony that the flotation test result was worthless because it could easily be explained by decomposition gases.

In a landmark decision in November — 13 years after her conviction — the court found that authorities had violated Manuela’s presumption of innocence by overlooking a more plausible reason for her infant’s death: Manuela had suffered from severe preeclampsia, a condition affecting pregnant women that can result in a sudden delivery and death of the baby.

The ruling energized activists who have been working to help imprisoned women who say they’ve been wrongly convicted.

In El Salvador, several women who were convicted of killing their newborns have been released.

In Argentina, Natalia Saralegui Ferrante, a law professor at the University of Buenos Aires who has looked for women by searching judicial sentences online for “fetus” and other keywords, hopes authorities will take greater interest in finding more cases and correcting injustices.

“How many are there in total today? No one knows,” said Saralegui, who recently published a book about seven women convicted of killing their newborns. “There’s no national office that has made finding these cases part of its agenda.”

In 2010, Las Libres, a feminist group in Mexico that interviewed women in prison to find mothers accused of killing their infants, successfully lobbied the state of Guanajuato to lessen its penalty for such cases, an effort that led to the release of at least eight women.

“In Guanajuato, we know about these cases because we looked for them,” said Veronica Cruz, one of the group’s founders. “And that means that these cases could happen in the entire country.”

::

Back in Umán, Guadalupe has been free while her case moves through the legal system.

Unlike many women in her situation, she has a private defense attorney, Rene Ramirez, who agreed to take the case after a local newspaper wrote about her — without using her name — and a women’s rights advocate saw the story.

A federal court is considering whether to halt the criminal proceedings based on a motion by Ramirez that argues Guadalupe’s rights were violated because the public defenders originally assigned to the case failed to adequately represent her.

To make their case that the alleged murder was premeditated, prosecutors have accused Guadalupe of cutting the umbilical cord with a sharp object they say she must have brought with her into the bathroom. Ramirez said that prosecutors haven’t offered evidence that Guadalupe cut the cord, which can also break off on its own.

While Guadalupe waits for a decision, she lives in a small house with her father and four dogs, sleeping in a hammock in a mostly bare room. She is taking classes at a nearby university to become an elementary school teacher. When she’s not doing chores or studying, she occasionally gets together with friends.

Her family buried the baby in a cemetery a 20-minute walk from her house. She and her father named him Jorge Armando, after her grandfather.

Occasionally she leaves candles by the baby’s grave.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.