As police waited, children inside Texas school called 911 begging for help

- Share via

UVALDE, Texas — Children inside a Texas elementary school frantically called 911, begging for the police to save them, as a tactical decision by a commander kept 19 officers from storming a classroom in what a law enforcement official acknowledged on Friday was a mistake in judgment.

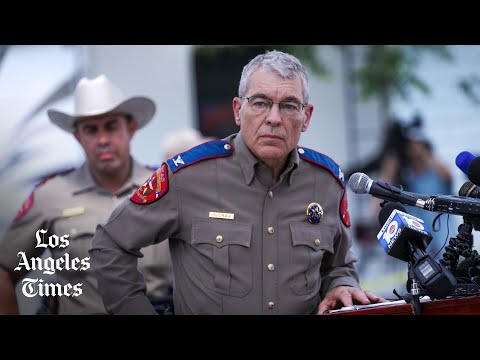

“Of course it wasn’t the right decision,” Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw said at a news conference, choking back tears. “It was the wrong decision. Period.”

With 19 officers, McCraw said, there were “plenty of officers to do whatever needed to be done.” But the commander inside — Pete Arredondo, the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District chief of police — decided the team needed more equipment and officers to enter the classroom where the shooter was holed up. He said the team did not move to take out the gunman until a full U.S. Border Patrol tactical unit arrived.

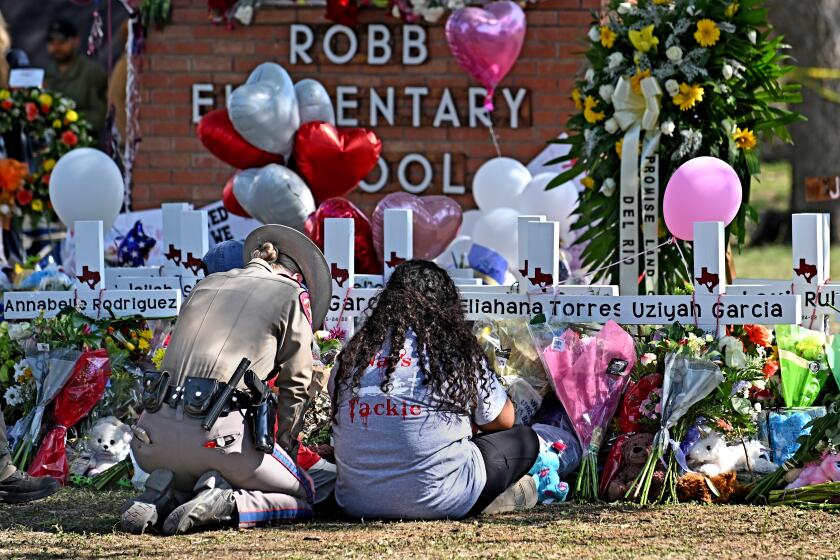

Nineteen children and two teachers died in the massacre Tuesday.

Authorities say children repeatedly called 911 from inside the school where a gunman killed 19 students and two teachers, including a girl who told the dispatcher, “Please send the police now.”

The magnitude of the mistake became glaringly clear Friday as officials also shared details of the 911 calls from children still alive in the barricaded classrooms.

At 12:03 p.m., McCraw said, a 911 caller whispered that she was in Room 112 and that multiple people were dead. Ten minutes later, she said eight or nine students were still alive.

More than half an hour later, a child calling from Room 111 said she could hear law enforcement officers next door. “Please send the police now,” she pleaded.

McCraw did not say how many children might have been saved had officers entered immediately. He also did not spell out the degree to which the commander was aware of the children’s 911 pleas.

“Ultimately, this is tragic. What do you tell the parents of 19 kids or the families of two teachers?” McCraw said. “We’re not here to defend what happened. We’re here to report the facts.”

McCraw emphasized that every officer in Texas has gone through active-shooter training and learns you go in without waiting — exactly the opposite of what officers did in Uvalde.

New photos from the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas

“Texas embraces active-shooter training, active-shooter certification,” McCraw said. “And that doctrine requires officers — we don’t care what agency you’re from; you don’t have to have a leader on the scene — every officer lines up, stacks up, goes and finds where those rounds are being fired at and keeps shooting until the subject is dead.”

Some parents whose children were in the school said they were even further troubled by the new timeline. Officers on the scene should have done more, they said.

“I understand that they’re afraid for their own lives, but these guys are in tactical gear,” said Laura Pennington, whose 8-year-old son, Adam, hid in the principal’s office as the massacre unfolded. “They could have swarmed the building from all angles. He was terrorizing these children. They needed to do more.”

Pennington, whose brother-in-law was among those who rushed to the school to help but were forcibly kept outside by officers, was eventually reunited with her son Tuesday afternoon. But she said she was in touch with a woman whose niece was wounded in the attack and was still hospitalized Friday.

“There’s several more that are critical and I don’t know if they’ll live,” Pennington said. “I want to cry because they deserve better than that.”

Law enforcement experts across the country were also shocked to learn new details of Tuesday’s police response, which ignored best practices adopted by Texas law enforcement to immediately send officers in to confront and kill active shooters.

“You’ve got to stop the bleed,” said Art Acevedo, former police chief of Miami, Houston and Austin, Texas. “You have to go in immediately. The kids were calling 911 for help.”

Travis Norton, a leader of the California Assn. of Tactical Officers’ after-action review team who has studied numerous mass shootings, said it is a common mistake in such situations to think “when the shooting stops, we stop.”

“That is the problem with the term ‘active shooter’: The shooter is still active if there are people in harm’s way,” he said.

The gunman posted his intentions on Facebook before shooting his grandmother, going to the elementary school and barricading himself in a classroom.

But law enforcement keeps making the same mistake, he said. In the 2018 Borderline Bar and Grill shooting in Thousand Oaks and the 2021 King Soopers grocery store shooting in Boulder, Colo., on-scene commanders mistook a lack of shots for a barricade situation, Norton said. In contrast, when a gunman attacked a Pittsburgh synagogue in 2018, officers did not stop when the killer stopped shooting.

Investigators in Uvalde are interviewing witnesses and poring over video to piece together a timeline that explains how the 18-year-old gunman, Salvador Ramos, was able to walk up to the school with a long gun, enter through an unlocked door and barricade himself inside two classrooms for nearly an hour before he was shot and killed.

With pressure mounting to explain the delayed response, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott scrapped plans to attend the National Rifle Assn.’s annual convention in Houston and traveled to Uvalde on Friday.

In his initial remarks, Abbott did not address errors by law enforcement or acknowledge previous misinformation he provided. Later, in response to a question from a reporter, he said he was initially “misled” about what happened in Uvalde and was “absolutely livid.”

“There are people who deserve answers the most — and those are the families whose lives have been destroyed,” he said. “They need answers that are accurate.”

For the second time this week, Abbott was confronted about his reluctance to support restrictions on guns. On Wednesday, former congressman and gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke accused Abbott of inaction. On Friday, state Sen. Roland Gutierrez, who represents Uvalde, urged Abbott to call lawmakers in for a special session to pass meaningful gun control measures.

Calling the massacre “unacceptable,” Abbott said Texas officials would look to pass the best laws to “make our communities and schools safer.” But Abbott said he would not consider a ban on assault-style rifles.

“Ever since Texas has been a state, an 18-year-old has had the ability to buy a long gun, a rifle,” he said. “Maybe we’re focusing our attention on the wrong thing?”

Earlier this week, Abbott hailed the speedy response of “valiant local officials” who he said had engaged the gunman before he entered Robb Elementary School.

“They showed amazing courage by running toward gunfire,” the Republican governor said at a Wednesday news conference. “And it is a fact that because of their quick response, getting on the scene, being able to respond to the gunman and eliminate the gunman, they were able to save lives.”

Actually, more than an hour and 20 minutes passed from when the gunman crashed his car outside the school at 11:28 a.m. until he was shot dead at 12:50 p.m.

That delay — as a crowd of anguished parents gathered outside and begged to get in to confront the gunman — has led to growing scrutiny of the law enforcement response to the deadliest U.S. school shooting in almost a decade. Some parents have criticized police for not stopping the shooter sooner, and San Antonio-area Democratic Rep. Joaquin Castro on Thursday urged the FBI to investigate local law enforcement actions.

Over the course of the week, Texas officials repeatedly changed the narrative of the timeline, leaving unexplained how the shooter had time to get into the school after the crash, enter through an unlocked door and barricade himself inside two classrooms. They also struggled to explain why local law enforcement officers apparently spent an hour inside the school “negotiating” with an active shooter.

Uvalde survivors’ stories: One fourth-grader said the shooter came into his classroom and said, ‘It’s time to die.’

Ramos’ rampage began just after 11 a.m., when he shot his grandmother in the face at her Uvalde home. According to officials, Ramos then posted a social media message declaring that “I’m going to shoot an elementary school” and drove off at a high speed in his grandmother’s pickup.

At 11:28 a.m., Ramos crashed the truck in a ditch and jumped out of the passenger side, carrying a rifle. He fired at two people at a funeral home as he walked toward Robb Elementary, climbed a fence and crossed the school parking lot.

The pull of family is strong in the close-knit community of Uvalde, Texas.

At 11:33 a.m., the gunman entered the school and began shooting more than 100 rounds into adjoining Rooms 111 and 112.

Two minutes later, three Uvalde Police Department officers entered the school through the same door used by Ramos and went directly to the classroom door. Two officers received grazed wounds from the suspect.

They were soon followed by three other Uvalde police officers and one county deputy sheriff, McCraw said, making a total of seven officers. By 12:03 p.m., as many as 19 officers were in the school corridor.

But it was not until 12:50 p.m. — more than an hour after law enforcement entered the building — that officers “breached the door” using keys they were able to get from a janitor. A Border Patrol tactical officer shot and killed Ramos.

The new timeline raises questions not just about a slow active-shooter response, but glaring security lapses in a school district that has invested in threat-assessment teams, a threat-reporting system, social media monitoring software, fences around schools and motion detectors to detect campus breaches.

According to online district records, “teachers are instructed to keep their classroom doors closed and locked at all times.”

A gunman killed 19 children and two adults at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, about 80 miles west of San Antonio, on May 24, 2022.

Even though Uvalde is a small city, population 16,000, its school district has its own police department, formed a few months after the 2018 school mass shooting in Parkland, Fla. It has six officers and one security guard.

Arredondo, the school district police chief who made the decision not to immediately send officers into the classrooms, spent 20 years on the Uvalde Police Department and was elected to the Uvalde City Council this month.

In 2020, when Arredondo was hired as chief, the school district’s superintendent, Hal Harrell, said in a Facebook post that the board of trustees was “impressed with his experience, knowledge, and community involvement.”

“We can never have enough training,” he told the Uvalde Leader-News.

In March, Arredondo posted on Facebook that the department had hosted “active shooter training” at Uvalde High School. A flier for the training declared: “Stop the killing.”

Arredondo did not respond to requests for comment.

One of the department’s newest hires, Officer Adrian Gonzalez, had been an assistant commander and SWAT training commander at the Uvalde Police Department for 10 years and has taken training courses in advanced SWAT tactics and how to respond to active shooters and rescue hostages.

Uvalde law enforcement officers have repeatedly participated in active-shooter training courses, according to official statements and online documents.

In April 2018, the Uvalde Police Department and the Uvalde County Sheriff’s Office took part in a five-day active-shooter response course conducted at the Middle Rio Grande Law Enforcement Academy. The training included mock scenarios at various public places, including an elementary school, police said.

In October of that same year, a mock active-shooter drill was held at Sabinal High School, about 20 miles east of Uvalde. The drill included members of the Uvalde County Office of Emergency Management, Border Patrol and Texas Department of Public Safety, according to the department.

Police also had experience with credible threats. In April 2018, about two weeks after the training at Middle Rio Grande, Uvalde officers arrested two juveniles who they said were “planning to conduct a school shooting on their senior year (2022) at the Uvalde High School.”

On Friday, McCraw said Ramos was not one of those juveniles.

On May 16, 2018, a school resource officer responded to a possible threat of a school shooting at Uvalde High after a student stated she “overheard a comment in the hallways that a school shooting was going to occur sometime today,” according to a new release. Police were not able to identify the person who may have made the comment.

Eight days later, on May 24, Uvalde High was placed in temporary lockdown while officers investigated a school shooting threat. An investigation “revealed that the concerning information was from a previous threat investigation and was cleared without incident,” police said.

Rector reported from Uvalde, Jarvie from Atlanta and Winton and Smith from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske in Houston contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.