Mexicans vote on whether to recall the president, an election he pushed for

- Share via

TEPETITÁN, Mexico — Signs displaying the smiling image of Mexico’s president hang outside many houses in his tiny, rural hometown in the southeastern state of Tabasco.

Some residents of Tepetitán remember Andrés Manuel López Obrador playing baseball as a boy. Many of them danced in the street when he became president in 2018 in a landslide.

In recent days, numerous residents appeared ready to vote for him again.

“He lived in poverty, like us. He was raised in the campo,” said Ardelio Morales Martinez, 56, a motorcycle taxi driver who had stopped Saturday outside Tepetitán. His taxi displayed a poster calling on people to vote for López Obrador.

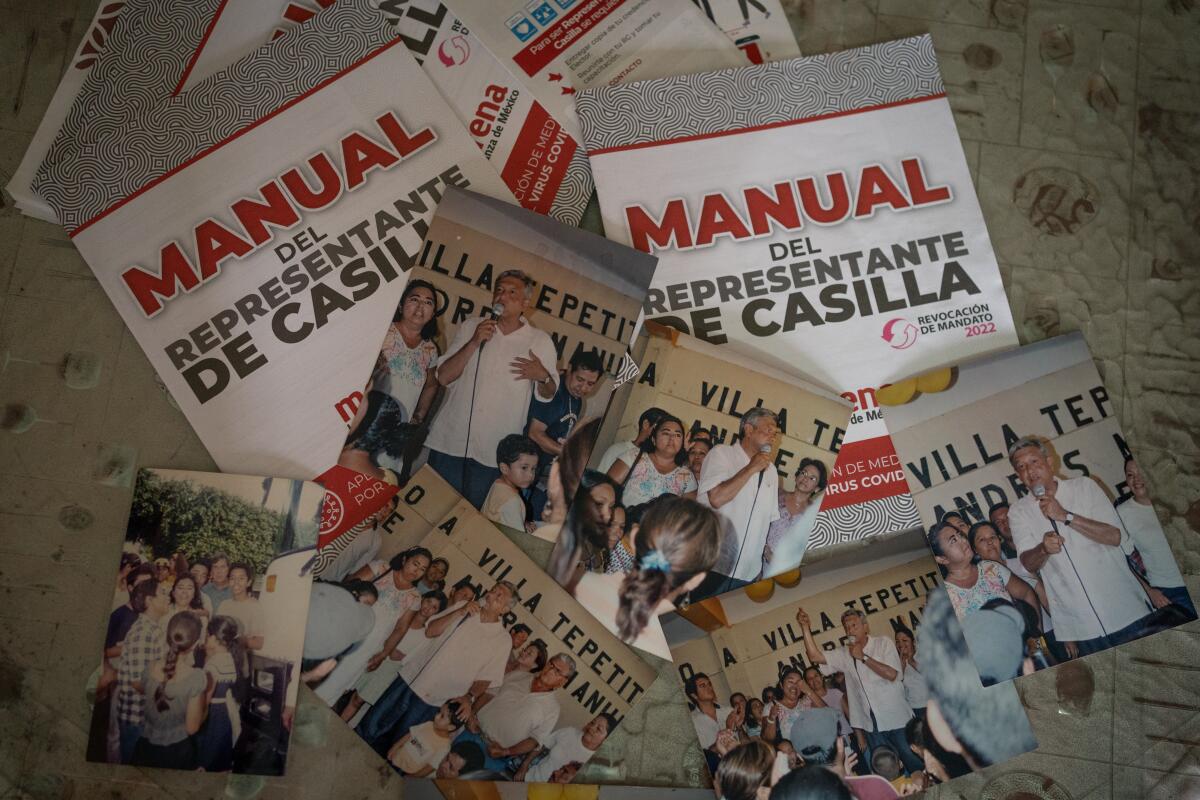

Mexicans on Sunday were deciding whether to boot their president from office two years early — a recall election that was unusual not only because it was the first in the country’s history but because the president pushed for it himself. The referendum was authorized by a 2019 constitutional reform led by López Obrador, who described the vote as an exercise to strengthen Mexico’s democracy.

“No one should forget that, that the people are the ones in charge,” he told a crowd after voting at a polling station in Mexico City.

Election officials late Sunday estimated that about 90% of those who went to the polls cast their ballot for the president, but that overall turnout only reached between 17% and 18% of a total of more than 92 million eligible voters. That fell far short of the 40% required for the result to be binding.

López Obrador, who became the country’s leader after promising a radical transformation to combat corruption and inequality, was not expected to lose. Polls show that about 60% of Mexicans approve of the job he’s doing as president.

Opposition leaders urged citizens to sit out the recall, accusing the popular president of twisting the purpose of the referendum into a tool to boost his power. They pointed to how across Mexico billboards and taxis bear the hashtag #QueSigaAMLO, encouraging more time for the president, who is commonly referred to by his initials, AMLO.

The National Electoral Institute, an independent agency organizing the recall, had ordered politicians from the president’s party to remove tweets it considered illegal government propaganda around the time of the election.

“I obviously won’t be participating,” Gina Andrea Cruz Blackledge, a federal senator representing Baja California from the PAN opposition party, said in an interview before the vote, calling the recall “a threat to democracy.”

“We’re not going to vote!!” wrote former Mexican President Vicente Fox on Twitter.

“The purpose of this referendum is that López Obrador shows muscle, that he shows that he continues to be a very popular president,” said Benito Nacif, a political scientist at Mexico City’s Center for Research and Teaching in Economics. “He’ll continue with a fresh mandate from the electorate.”

López Obrador, a leftist populist who has vowed not to cater to privileged classes, has expanded social welfare programs for elderly people, those with disabilities and farmworkers.

Drawing on nationalistic rhetoric, he’s focused on building large infrastructure projects, including an airport outside Mexico City that he unveiled last month after scrapping a flashier airport started by his predecessor. Others in progress include a tourist train in the Yucatan Peninsula and the Dos Bocas oil refinery in Tabasco, part of his effort to limit Mexico’s reliance on gas imports.

His critics say that he’s downplayed the violence of criminal networks in different parts of Mexico as a national security issue and hasn’t done enough to address killings of women and journalists. At least eight journalists have been killed this year. After the European Parliament last month passed a resolution calling on López Obrador to protect journalists, he responded that “we are no longer anyone’s colony” — a reaction that critics said showed an unwillingness to do more to address the slayings.

“The president has appealed to sovereignty and nationalism and they are two cards that the public opinion has bought,” said Alejandro Moreno Álvarez, a political scientist at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico in Mexico City.

His approval rating, which topped at 67% in his first few months in office, fluctuated between the high 50s and mid 60s in 2021, according to Ana María Hernández, the director of investigation for the Mitofsky polling group. It recently bumped down with the publication of an article reporting that one of the president’s sons has been living ostentatiously in contrast with the president’s austere image.

In Mexico City’s Anáhuac district, two neighbors sitting on a park bench last week passionately debated the recall. Guadalupe Ortiz, 67, said that she “loves López Obrador with all my heart” and Jorge Armando Solis, 42, accused the president of diverting attention from how criminal networks control areas of the country.

“I’m not going to vote, I’m not going to fall into a farce,” he told her.

With the opposition calling for Mexicans to stay home, the recall had turned into a test of how well the president’s party, known by its acronym Morena, can mobilize its base.

Moving forward with the recall election required the signatures of at least 3% of eligible voters, or 2.7 million people. Pro-López Obrador civil society groups like Que Siga La Democracia, or “may democracy continue,” worked furiously last fall to reach that amount, gathering about 20,000 volunteers from across the country to collect signatures, according to its president, Gabriela Jiménez Godoy.

Gerard Traverse, a 35-year-old staffer who focuses on environmental education for the National Institute of Political Formation of Morena, had knocked on doors in his neighborhood in Morelia, the capital of the state of Michoacán, to see if people knew where to vote and to offer rides to the polls.

“[We] try to fight against fake news, that this exercise is a waste of money,” he said. “I see this as a civic duty because we’re getting a possibility that hadn’t existed historically.”

In Tabasco, the president’s home state of more than 2 million people where just over half of the population lives in poverty, many say they feel the effect of the president’s work.

Mario Rafael Llergo, a federal congressman from Tabasco, said that the Dos Bocas refinery in the coastal town of Paraiso has created thousands of jobs. Brontiz López, a member of Paraiso’s government council who can see the construction project’s cranes from his home, said that the refinery brings national pride to Mexico.

“It’s no longer a land of conquests,” he said, echoing the president.

Others voting Sunday were longtime followers of López Obrador.

Carlos Benito Lara was a university student in the 1990s when he spent weeks walking with López Obrador and agriculture workers on a march from Tabasco to Mexico City to protest alleged electoral fraud. Lara said López Obrador would tell passersby that they were fighting for marginalized people who lacked representation in politics.

“I felt like a social justice fighter,” he said, recalling how López Obrador told him at the time “that the true leftist ideology is to help others.”

In Tepetitán, a community of a couple thousand people where chickens often waddle around freely and fishermen dock their boats in a river running through town, residents say that the president has not forgotten them.

During his time in office, the federal government has remodeled the town’s homes and constructed new houses for families in need. Some say they’ve benefited from a federal forestation program that pays farmers to plant trees.

Carlos Lopez Paz, who runs a ranch just outside Tepetitán, grew up with López Obrador and later attended university with him in Mexico City. He had been telling people all week to vote for the president.

“We are now seeing the other side of the coin,” he said. “The money is reaching the masses and it’s not staying with just a few.”

Petrona Occegueda Cruz, 72, moved a month and a half ago into a new home in Tepetitán that she said was built by the federal government. A sign supporting the president hangs by the front door over chunks of concrete that still litter the walkway to the house.

“I had never before received support from anyone,” Occegueda said, adding that the president visited the town after it was damaged by floods in 2020.

Occegueda said she was grateful for an elderly persons pension that López Obrador has promoted, which she uses to pay for food, electricity and medicine.

“He’s been an honest man and is from our town,” she said. “I feel joy because he is going to triumph again.”

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez in Mexico City contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.