To sink nuclear talks with the U.S., Iran’s hard-liners use a novel weapon: A hit TV show

- Share via

TEHRAN — It doesn’t star Claire Danes, it’s not about Al Qaeda and it won’t win any Emmys. But “Gando,” a hit “Homeland”-like show that swept Iran by storm, is having an impact far beyond the small screen, morphing into a real-life political force that could upset sensitive nuclear negotiations between Tehran and the West.

That’s exactly what its producers want. More than just a showcase for spectacular car chases and knotty storylines, the spy thriller is a sophisticated ploy by Iranian hard-liners eager to torpedo the nuclear talks, turning mass entertainment into a weapon in their battle against the country’s moderates.

The series, which stars some big names in Iranian showbiz, catapulted to success when it debuted in 2019, scoring the highest ratings ever on Iranian state television. Season 2 was pushed out onto the airwaves last March, in what appeared to be a bid to help sabotage Iran’s nuclear negotiations as they were starting to gain momentum.

The show is now a shibboleth of public discourse here, a byword among ultra-conservatives who praise it as a patriotic exposé and reformists who denounce it as slanderous propaganda. And with the nuclear talks possibly taking on some new traction after being stalled for months, “Gando” has, coincidentally or not, just gone back on air in reruns.

The series revolves around the real-life dialogue between Tehran and world powers, including the U.S. and U.K., to revive their moribund 2015 nuclear accord. But in its role as a Trojan horse for a political misinformation campaign, “Gando” spins its own web of made-up intrigue and dark ops.

The cast of characters includes American and British agents who are repeatedly foiled in their attempts at infiltration; a hardboiled Iranian intelligence officer named Mohammad, who gets blown up by terrorists in the recent season finale; and a thinly veiled version of Jason Rezaian, the Washington Post journalist who spent 18 months in an Iranian prison until his release in 2016.

More scurrilously, the Iranian nuclear negotiators on the show are portrayed as, at best, stooges of the West or, at worst, traitors out to subvert the Islamic Republic. In an episode that attracted particular controversy, Mohammad uncovers a secret connection between some of the negotiators and British intelligence as he investigates a scheme by the West to sow discord between Sunnis and Shiites.

“Chief, there’s a spy on the negotiating team we need to deal with,” Mohammad — played by well-known actor Vahid Rahbani — warns his boss.

Critics insist there is zero evidence that any members of the real negotiating team are spies. They lambaste “Gando” as a smear campaign against the reformist government of former President Hassan Rouhani and an effort to discredit his attempts at a rapprochement with the West.

That didn’t stop a group of 160 hard-line lawmakers who, as Rouhani tried to revive the atomic deal earlier this year, signed a letter endorsing the show and calling it an accurate depiction of events.

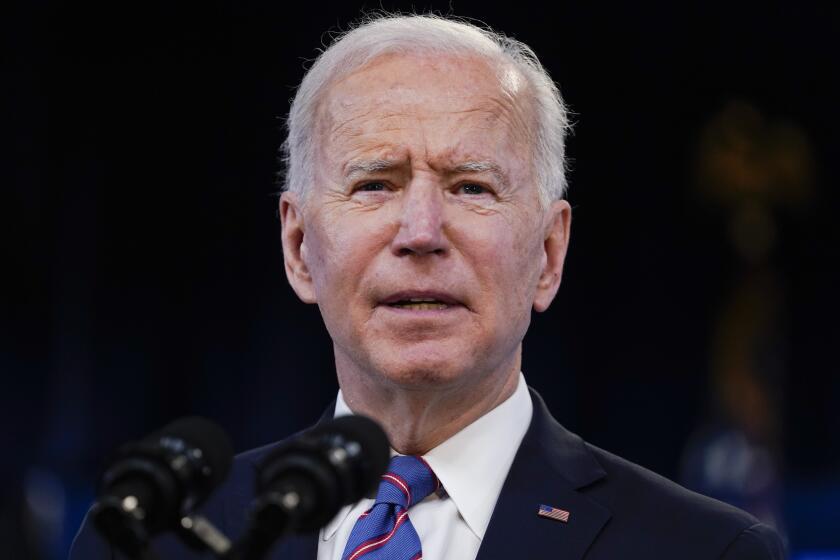

President Biden, meeting with European leaders to plot strategy for nuclear talks with Iran, offers to lift sanctions if Tehran ‘changes course.’

“If what we have seen in the ‘Gando’ thriller is true, why doesn’t the judiciary sue the negotiating team of the Rouhani government?” Javad Nikbin, an ultra-conservative member of parliament, demanded recently.

Such has been “Gando’s” success at muddling fact and fiction in many viewers’ minds that, during its first season, Iran’s then-foreign minister angrily — and repeatedly — excoriated it as a “pack of lies.” The minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, even wrote to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei complaining of the show’s baleful influence.

The program cost an estimated $5 million to make, a large budget by local standards, and included shooting on location in Turkey and China. It was produced by hard-line affiliates of Iran’s state TV, including ones aligned with Iran’s vaunted Revolutionary Guard military unit.

“Gando” — whose title refers to a small indigenous crocodile that craftily stalks its prey — constantly rehearses the argument that engagement with the West is tantamount to surrender, as is any retreat from Iran’s pursuit of nuclear capabilities. Blame for the dire state of the economy, which has been crippled by U.S.-led sanctions, lies firmly with hostile foreign forces and their domestic lackeys.

“People fully understand that economic hardship is due to the betrayal of a handful of pro-Western diplomats and politicians who sell the idea of negotiating with the West as the only solution to the problems of the country,” Mohammad declares in one episode.

Despite the efforts of “Gando’s” backers and Tehran’s often aggressive rhetoric, the nuclear talks are still alive, if feebly — unlike Mohammad, who dies in a fireball at the end of Season 2. And Iran’s foreign ministry, portrayed on the show as a nest of out-of-touch elites, has not been totally purged of its more moderate figures, even after the election in June of hard-line President Ebrahim Raisi, who succeeded Rouhani.

Earlier this month, Tehran’s chief negotiator announced that he would meet with representatives from the other signatories of the nuclear deal, including the U.S., in Vienna on Nov. 29. That has buoyed hope in some quarters that the accord might still be salvaged, with the approval of Khamenei.

“The hard-liners have spared no efforts to affect the talks in the past few years, but it is still the supreme leader who has the final say,” Mostafa Tajzadeh, a reformist politician and former deputy interior minister, said in an interview. “Despite all the attempts taken by the hard-liners, I do believe that the Biden administration still controls the initiative to break the deadlock.”

Iran and the U.S. are finally talking, but not face-to-face

And not all Iranians have been taken in by “Gando’s” fabrications.

Reza Parasteh, a 40-year-old IT engineer in Tehran, said the opening episodes of the show’s first season were good in terms of plot and production values. But then the show became a strident piece of agitprop that strained credulity.

“Season 2 was a patched-up cock-and-bull story and extremely political to attack the likely deal by the outgoing government,” Parasteh said.

Still, “Gando” has firmly implanted itself in the popular mind, continuing to crop up in public discourse even after the second season finished airing. The hashtag “Gando” regularly trends on Twitter in Farsi following events with seemingly shadowy origins, such as a cyberattack at the end of October that knocked gas stations offline around the country, giving rise to long queues of cars and angry motorists. There was no claim of responsibility for the incident.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“Let’s call on Mohammad and his team on ‘Gando’ to thwart the conspiracy behind the hacking of the gas stations,” one pseudonymous activist tweeted sarcastically.

The nakedly political stance of the show, especially in the latest season, has triggered a backlash from detractors, not just against the series but also against some of its stars. One actor complained of being turned down for roles in projects by independent producers because of her appearance on “Gando.”

Another actor, Dariush Farhang, a pioneer of Iranian cinema and theater, found himself accused of trading his reputation for the money he made from playing an intelligence chief on the show. When photos of Farhang out shopping in Toronto were posted online, some of his compatriots responded scathingly: “You depicted the West as filthy, and yet you do your shopping there.”

“Gando’s” producers have promised more seasons of their hit series.

As climate change and poor management cause greater water scarcity, Tehran and much of Iran are sinking from land subsidence.

Its fans are no doubt excited. Its critics are still fuming over what they see as sinister manipulation by a faction of Iranian society to get the public on its side.

“It is made to impose the will of a minority on a majority of people … using drama and fiction,” veteran journalist Mehrdad Khadir said. “It is absolutely not an artistic piece. Rather, it’s an attempt to affect the future of those who enjoy it as entertainment.”

Khazani is a special correspondent based in Tehran. Staff writer Chu is based in London.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.