The secret-poll watchers of Nicaragua. How they monitored a questionable presidential election

- Share via

They planned their mission for months, communicating through encrypted texts to avoid detection by authorities.

The Nicaraguan government had excluded traditional international monitors to scrutinize the presidential election Sunday. So about 1,450 volunteers stationed themselves at 563 voting centers across the country to do the job themselves.

There was little doubt who would win. In the run-up to the election, the government of Daniel Ortega, a former guerrilla who has been president since 2007, had arrested seven potential candidates and jailed dozens of critics. Officially, his Sandinista National Liberation Front captured 75% of the vote.

The grass-roots poll-watching effort, led by a group known as Urnas Abiertas (Open Ballot Boxes), brought some transparency to an election widely denounced as illegitimate. Volunteers observed paramilitary surveilling voting sites, Sandinista militants pressuring residents to vote and government vehicles being used to transport residents to the polls.

But most surprising was its estimate that only 18.5% of eligible Nicaraguans had voted — far below the official turnout of 65%.

In a country with little political freedom, it appears that many Nicaraguans heeded the call from opposition activists that urged residents to boycott the election and spread the hashtag #QuedateEnCasa, or “stay home.”

“In silent form, we saw activism,” said Juan Diego Barberena, a 25-year-old leader of Blue and White National Unity, an opposition movement that said eight of its members were illegally arrested the day before the election. “It’s a lesson to all Nicaraguans that if we unite we can reject the dictatorship.”

The reelection of Ortega was swiftly condemned as undemocratic by the European Union, neighboring Costa Rica and the United States. In a speech Monday, Ortega said that his critics in prison were the “sons of the female dog of Yankee imperialists.”

Instead of independent election monitors, the government said it credentialed more than 200 “electoral companions” from foreign groups considered friendly to the Sandinista government.

The National Assembly, controlled by the ruling party, released a statement saying observers “appeared pleased with the free and democratic Nicaraguan electoral process.” The Supreme Electoral Council, which oversees elections, did not respond to a request for comment on the observations made by Urnas Abiertas’ poll-watchers.

Urnas Abiertas was formed last spring and is run by a handful of people across academic disciplines, according to Pedro Fonseca, one of its founders. It partnered with five civilian groups to recruit election monitors.

One volunteer said she visited three voting centers in her small town — traveling on foot, by car and on a motorcycle to throw off anyone who might be tracking her.

“You don’t feel fear, you feel that at least you’re doing something,” said the 20-year-old student, who would give only her first name — Alejandra — out of fear for her safety. “This is something you can do for your country even though it’s not that significant.”

Throughout the day, she stayed in touch with her family. She said she saw about five people enter the voting centers every hour.

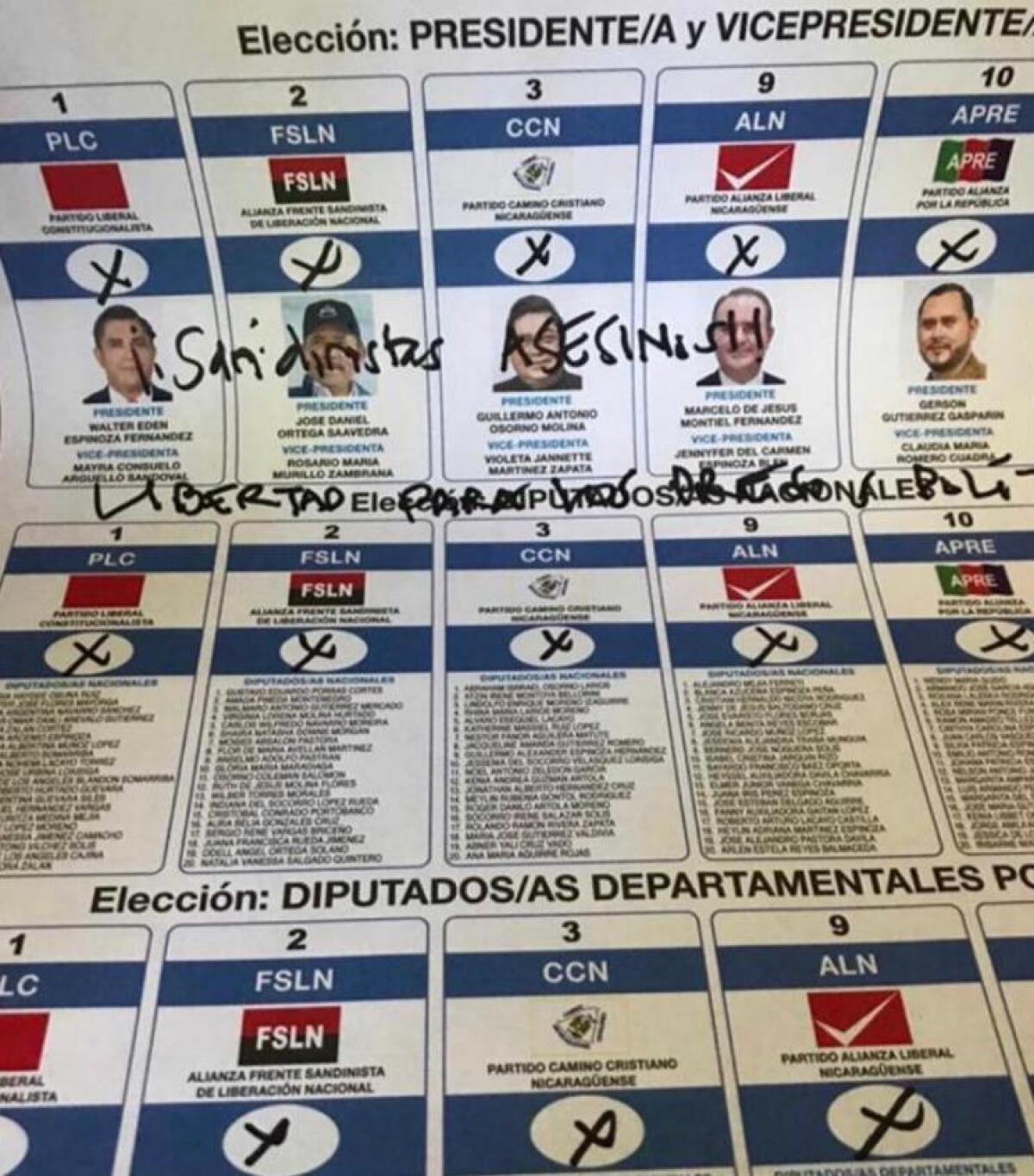

Some government workers sent her pictures showing how they annulled their vote by checking off boxes for multiple candidates or writing messages like “freedom for the political prisoners” or “free Nicaragua.”

When she returned home, she closed the doors and windows, suddenly worried about backlash.

“I think it’s in that moment that one is aware of the risk,” she said.

Despite their attempts to be discreet, several other observers were detained.

Jennie Lincoln, a senior advisor on Latin America at the Carter Center who has helped monitor past Nicaraguan elections, praised the group’s effort.

“At high, high personal risk, domestic monitors were able to gather information about what was happening on election day when the government had put into place numerous obstacles to any serious election observation effort,” she said.

The group’s turnout estimate of 18.5% was based on voter counts at about a fifth of the country’s polling stations.

“It’s very hard to have certainty about a number, but the fact we have photos and videos from across the country that shows empty polling stations suggests this figure might easily be correct,” said Hilary Francis, a historian of Nicaragua at Northumbria University in England.

Opposition leaders said the turnout would probably have been lower if not for government efforts to compel people to vote.

Barberena said observers reported seeing voters being delivered to the polls in government vehicles and members of Councils of Citizen Power — neighborhood committees that are controlled by the Sandinista party — going from house to house, telling residents to vote early and reminding them that they have benefited from government social programs.

He also heard from a medical student who reported having been asked to show her inked thumb as proof of her vote before entering a military hospital in Managua. The Nicaraguan newspaper La Prensa reported on similar cases.

“We live a political violence in Nicaragua when the Sandinista front thinks it can do what it wants with public workers and students,” Barberena said.

A 17-year-old student in Managua who would disclose only her first name — Ashly — said that four members of the neighborhood committees showed up at her home on election day morning to escort her family to a voting center in a truck.

“We’ve come to take you,” she recounted them saying.

Family members said they were going to church and would vote later. But when Ashly had returned home around noon, the committee members were waiting. Ashly and her relatives told them they would go to the polls at 3 p.m.

The committee members returned and escorted Ashly and her mother to the polls. The family convinced officials that Ashly’s grandmother couldn’t leave the house because of a toothache and that her great-grandmother couldn’t go because the pandemic made it too risky.

At the nearly empty voting center — only a two-minute drive away — Ashly crossed off boxes for all the candidates, annulling her vote.

“I was really nervous,” she said. “I thought, ‘Hopefully they don’t do anything.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.