Miami security company under scrutiny in assassination of Haiti president

- Share via

MIAMI — For the owner of a small private security company with a history of ignoring debts and declaring bankruptcy, it probably looked like a good opportunity: Find people with military experience for a job in Haiti.

Antonio “Tony” Intriago, owner of Miami-based CTU Security, seems to have jumped at the chance, hiring more than 20 former soldiers from Colombia for the mission. Now, the Colombians have been killed or captured in the aftermath of the July 7 assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moise, and Intriago’s business faces questions about what role it might have played in the killing.

On Wednesday evening, Leon Charles, chief of Haiti’s national police, accused Intriago of traveling to Haiti numerous times as part of the assassination plot and of signing a contract while there, but provided no other details and offered no evidence.

“The investigation is very advanced,” Charles said.

A Miami security professional believes that Intriago was too eager to take the job and did not push to learn details, leaving his contractors in the lurch. Some of their family members back in Colombia have said the men understood the mission was to provide protection for VIPs.

Three Colombians were killed and 18 are behind bars in Haiti, Colombia’s national police chief, Gen. Jorge Luis Vargas, told reporters in Bogota. Colombian diplomats in Haiti have not had access to them.

Three days after the assassination of Haiti President Jovenel Moise, it’s still unclear who ordered it and who did it. His security team is scrutinized.

Vargas has said that CTU Security used its company credit card to buy 19 plane tickets from Bogota to Santo Domingo, in the Dominican Republic, for the Colombian suspects in the killing. One of the Colombians who was killed, Duberney Capador, photographed himself wearing a black CTU Security polo shirt.

Nelson Romero Velasquez, an ex-soldier and attorney who is advising the families of 16 of the Colombians held in Haiti, said Wednesday that the men had all served in the Colombian military’s elite special forces and could operate without being detected if they had desired. He said their behavior made it clear that they did not go to Haiti to assassinate the president.

“They have the ability to be like shadows,” Romero Velasquez said.

The predawn attack took place at the president’s private home. He was shot to death and his wife wounded. It’s unclear who pulled the trigger. The latest suspects identified in the sweeping investigation include a former Haitian senator, a fired government official and an informant for the U.S. government.

If the international community insists on supporting men connected to Jovenel Moise, there will be no free and fair elections in a nation devastated by corruption and poverty.

Miami has become a focus of the inquiry. The city has long been a place for intrigue, including being a CIA recruitment center for the failed Bay of Pigs operation to overthrow Cuban dictator Fidel Castro and serving as a key shipment point for Colombian cocaine in the 1980s. Its palm-fringed shores have also been a place of exile for people from Latin American and Caribbean countries when political winds blew against them at home, and where some plotted their returns.

Homeland Security Investigations, a U.S. agency responsible for inquiries into crimes that cross international borders, is also looking into the assassination, said a Department of Homeland Security official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk about the case. He declined to provide details.

The FBI says it is “providing investigative assistance” to Haitian authorities.

Intriago, who immigrated to the U.S. from Venezuela over a decade ago and participated in activities in Miami opposing the leftist regime in his homeland, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

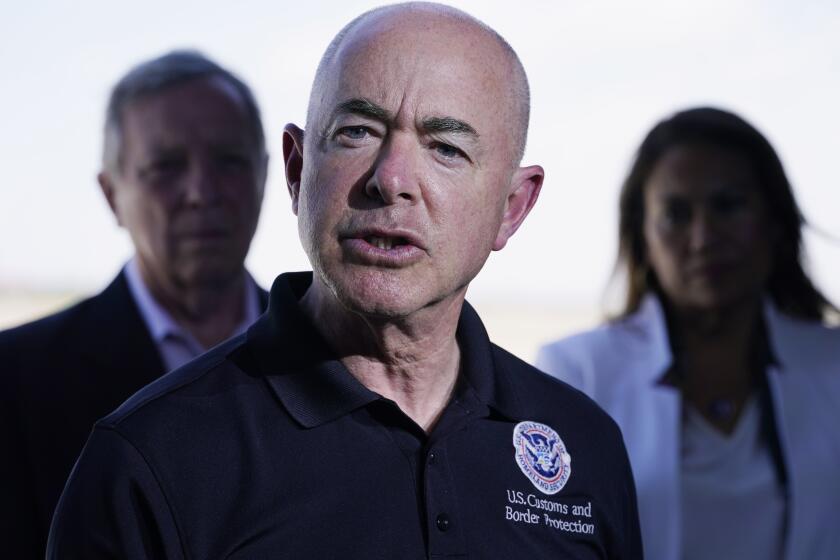

Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas warned Cubans and Haitians not to try to come to the United States illegally by sea and said they would not be allowed in.

He likes to be around powerful people and has posted photos on social media showing himself with them, including Colombian President Iván Duque.

The Colombian leader’s office Monday disavowed any knowledge of Intriago, saying Duque was in Miami while campaigning for the presidency in February 2018. The president’s office said Duque posed for photographs with some of those in attendance, but he did not have any meeting or any ties with Intriago.

Florida state records show Intriago’s company has changed names in the last dozen years; its names included CS Security Solutions and Counter Terrorist Unit Federal Academy.

CTU lists two Miami addresses on its website. One is a shuttered warehouse with no signage. The other is a small office suite under a different name. A receptionist said the CTU owner stops by once a week to collect mail.

The escalation of gang violence in Haiti threatens to complicate efforts to recover from last week’s brazen slaying of President Jovenel Moise.

The company website says it offers “first-class personalized products and services to law enforcement and military units, as well as industrial customers.”

But it ducked paying some wholesale companies for their products. Florida records show Intriago’s company was ordered by a court to pay a $64,791 debt in 2018 to a weapons and tactical gear supply company, RSR Group. Propper, a military apparel manufacturer, also sued for nonpayment.

Alexis Ortiz, a writer who worked with Intriago organizing meetings of expatriate Venezuelans in the United States, described him as a “very active, skilled collaborator.”

“He seemed nice,” Ortiz said.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Richard Noriega, who runs International Security Consulting in Miami, said he does not know Intriago personally but has been observing the developing situation. Noriega, who is also originally from Venezuela, believes Intriago was lured by the prospect of fast money and did not perform due diligence.

Putting himself in Intriago’s shoes, Noriega said: “I’m coming out of a complicated situation — of work, of income, of money. An opportunity arises. I don’t want to lose it.”

Normally, a security company would seek all the details of an operation, to determine how many people to use and what level of insurance they would need. A priority would be to plan an escape route in case things go awry, he said.

“The first thing we [security professionals] have to take into account is the evacuation. Where will they exit? That’s the first thing I do,” Noriega said.

The assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse is the Caribbean nation’s latest tumultuous chapter.

But apparently that planning never happened, perhaps because the Colombians, or at least some of them, thought their mission was benign.

He said it does not seem logical that the highly trained Colombians would not have had an escape route if they were there as assassins. Instead they were caught, some hiding in bushes, by the local population and police.

“It is very murky,” Noriega said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.