Few U.S. states require a waiting period to buy a gun, but that may be changing

- Share via

Not long before the deadly Atlanta-area shootings spread fear and anger through Asian American communities nationwide, police say, the attacker made a legal purchase: a 9 mm handgun.

Within hours, they say, he had killed eight people, seven of them women and six of Asian descent, in a rampage targeting massage businesses.

If Georgia had required him to wait before getting a gun, lawmakers and advocates say, he might not have acted on his impulse.

“It’s really quick. You walk in, fill out the paperwork, get your background check and walk out with a gun,” said Robyn Thomas, executive director of the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “If you’re in a state of crisis, personal crisis, you can do a lot of harm fairly quickly.”

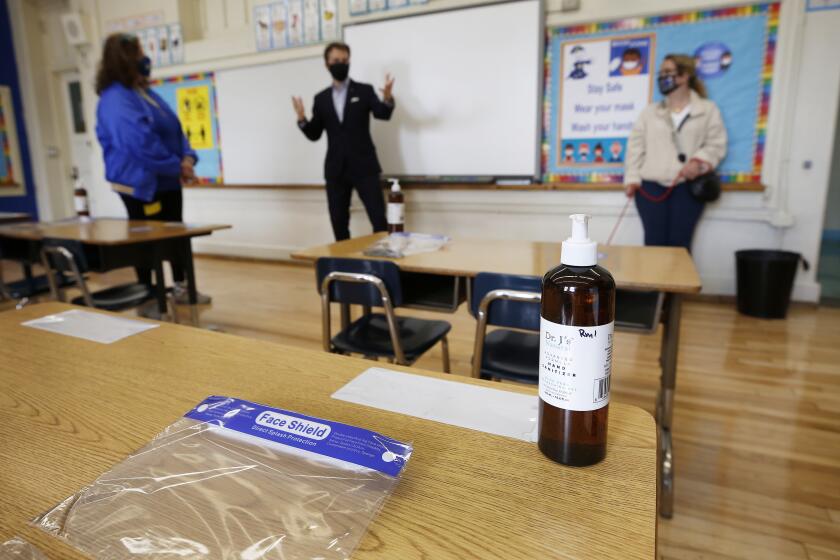

Students can sit three feet apart in classrooms, instead of four or six, potentially allowing schools to avoid hybrid, part-time schedules. L.A. Unified will stick with six feet.

The purchase was a normal transaction at Big Woods Goods, a shop north of Atlanta that complies with federal background-check laws and is cooperating with police, said Matt Kilgo, a lawyer for the store.

“There’s no indication there’s anything improper,” he said.

The vast majority of states are like Georgia, allowing buyers to walk out of a store with a firearm after a background check that sometimes can take minutes. Waiting periods are required in just 10 states and the District of Columbia, although several states are considering legislation this year to impose them.

Gun control advocates say mandating a window of even a couple of days between the purchase of a gun and taking possession can give more time for background checks and create a “cooling off” period for people considering harming themselves or someone else. Studies suggest that waiting periods may help bring down firearm suicide rates by up to 11% and gun homicides by about 17%, according to the Giffords Center.

Georgia Democrats plan to introduce legislation that would require people to wait five days between buying a gun and getting it, said Rep. David Wilkerson, who is minority whip in the state House.

“I think a waiting period just makes sense,” he said.

A 2020 analysis by the Rand Corp., a nonprofit think tank, also found that research links waiting periods to decreased suicide and homicide rates but determined that the effect on mass shootings was inconclusive because the sample size was too small.

California has one of the country’s longest waiting periods — 10 days. That did not stop more than 1.1 million people from buying guns last year, which was just shy of the record number sold in 2016. Gun sales nationwide, meanwhile, surged to record levels last year amid pandemic-related uncertainty.

Against that backdrop, lawmakers in at least four states — Arizona, New York, Pennsylvania and Vermont — have proposed creating or expanding waiting periods.

New gun laws will not fix deep-seated problems such as racism, misogyny and violence, said Seo Yoon “Yoonie” Yang, a leader with Students Demand Action, a gun violence prevention group. But they can help keep guns out of the hands of people who would do harm in the meantime, she said.

“Legislation is practical. Research shows that it works,” she said. “It is change that can happen efficiently and quickly.”

In Colorado, Democratic state Rep. Tom Sullivan ran for office after his son, Alex, died along with 11 others when a gunman opened fire in an Aurora movie theater eight years ago. Sullivan said he hoped a waiting period in legislation he was planning to sponsor could help curb domestic violence and suicide.

“In Atlanta, imagine if this guy’s parents or somebody else were notified that he was trying to get a firearm. Maybe they could have helped,” he said. “It wouldn’t have hurt anybody to wait ... let it breathe a while. If there’s a problem, let it surface, we’ll sort it out.”

Gun rights groups, including the National Rifle Assn., oppose waiting periods. The group points to 2018 federal firearm-tracing data that shows the average time between first retail sale of a gun and involvement in a crime was nearly nine years. They also argue that waiting periods create a delay for people buying legally, while leaving illegal weapons transfers unaffected.

“A right delayed is a right denied,” Second Amendment Foundation founder Alan Gottlieb said.

Gun control legislation also is making its way through Congress. The Senate is expected to consider a bill to expand background checks, but it faces a difficult road — Democrats would need at least 10 Republican votes to pass it. Although the House approved two bills to strengthen the checks this month, Congress has not passed any major gun control laws since the mid-1990s.

In Georgia, the Republican-controlled Legislature may resist new firearms laws before it concludes business at the end of the month. But Wilkerson pointed to recent long-sought victories that once seemed improbable, including passage of a hate crimes law and the likely repeal of a citizen’s arrest law a year after the death of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man pursued by armed white men while jogging.

“You’re going to run into resistance. It doesn’t mean you don’t try,” Wilkerson said. “In tragedy, sometimes we can move forward. This may be the opportunity to look at another tragedy and do something about it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.