- Share via

In a factory not far from a holy river, sewing machines hum in the morning light. Spindles whir and women feed fabric toward needles. Unlike most products this Thailand business churns out — shower caps, ponchos and aprons — what the women are stitching together on the second floor will be used only once.

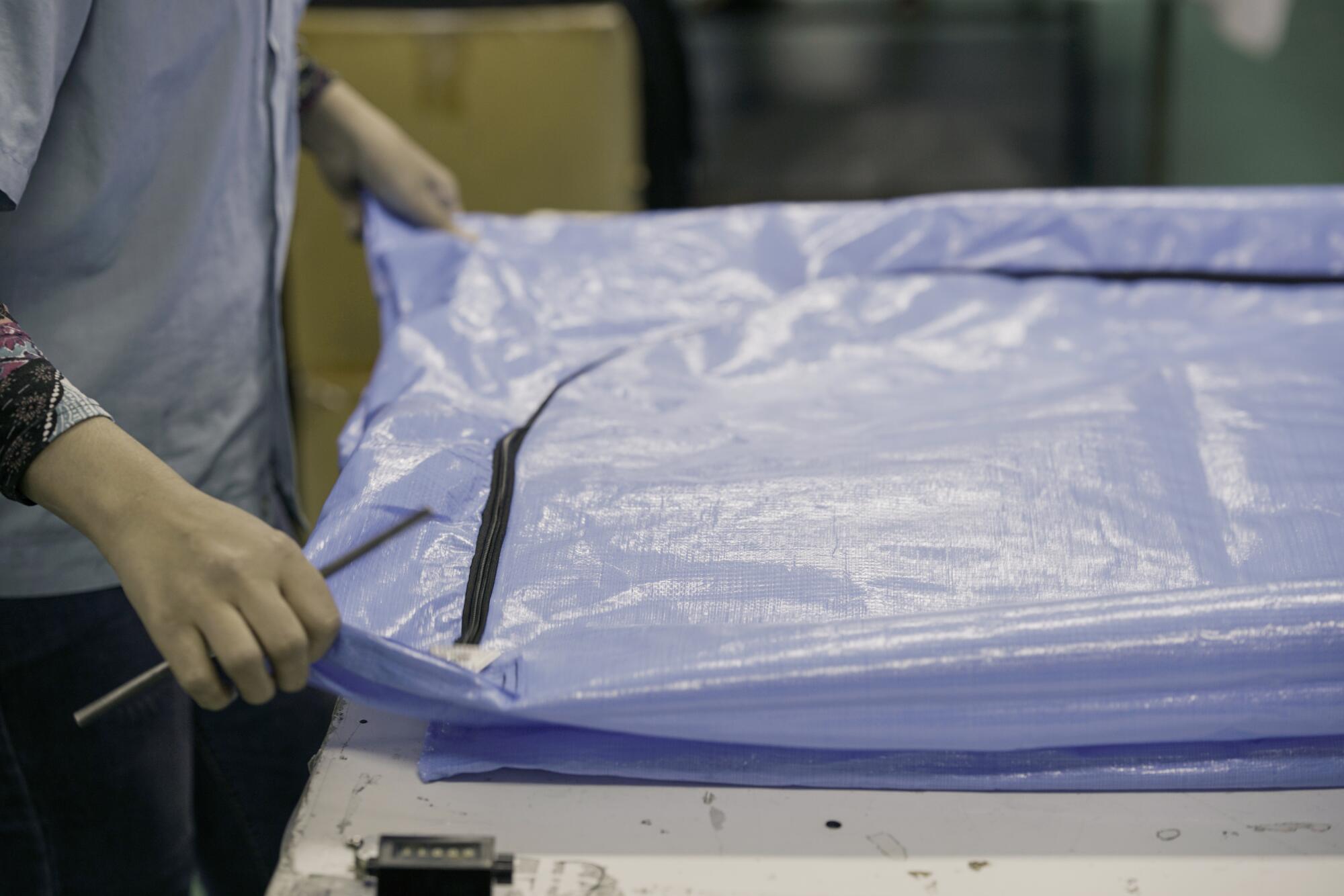

Siriphon Chakpangchaluem keeps an eye on it all. Her hair bunched under a white cap and her arms crossed against her smock, she has been at the Winbest Industrial plant for more than 13 years, ascending from assembly line to deputy manager. She has watched as designs have been improved and knows that high-density polyethylene can be woven to be leak-resistant.

The women under her charge work in pairs. They maneuver 94-inch strips of tarp. They cut and fold. They weld edges together with radio waves. Spools yank in rackety spin. Hands move swift as bird wings, and toward the end, when what they are making takes shape, the women fasten on long, curved zippers and fold their handiwork into neat rows of black, white and blue.

One of them will be delivered 8,545 miles away to Wanda Mathis-Conner’s house, but the Michigan mother doesn’t yet know this.

When the seamstresses are done, dozens of men carry what they have made downstairs and pile it in cases stacked 6 feet high. Forklifts wedge the cases into 40-foot shipping containers, like the one marked THAF48823 that on Sept. 26, 2019, is driven 42 miles south: across the Bang Pakong River, along the northern coast of the gulf, and into Laem Chabang Port’s Terminal C.

The container sits for days waiting for a freighter. It holds 37,000 pounds of Manufacturer Product #11-224.

Body bags.

***

The COVID-19 pandemic was months away from sweeping the world on Oct. 4, 2019, when, eight minutes after noon, the MOL Premium, a Panamanian cargo ship that stretched three football fields long, set sail, wrapping east around the tip of Vietnam and bound for America.

At that moment, an ocean and half a continent away, Wanda Mathis-Conner was driving through downtown Detroit, her black van cluttered with backpacks and artwork, along with knick-knacks her eldest brother, Warren, had picked out for her on a recent trip to Veterans Affairs.

It was her 55th birthday, and “Ma,” as her daughters Riann and Raven called her, had spent it at a funeral.

The girls’ Aunt Lisa on their dad’s side had died after years of battling a drug addiction. Ma knew all about that. Her daughters’ father had struggled with drug abuse and was largely absent for years when they were in elementary school.

Ma raised Riann, 33, and Raven, 31, mostly alone, working as a delivery truck driver for Frito-Lay chips and taking customer calls for Comcast. She later became caregiver for the elderly, including dementia patients. She and her girls lived in a small brick house that held four generations of her family stretching from Riann and Raven’s children to Ma’s mother, whom everyone called Granny.

Ma — who had hoped of riding on a Harley one day along the Detroit River — was the center of things. She had been in the operating room when Riann, who would earn a law degree, needed a C-section to deliver her son, Kaden. Every afternoon, she picked Raven’s daughter, London, up at school while Raven started up as a hairstylist. Ma paid the bills when the girls hit hard times, her van crisscrossing the city as she tended what needed to be done.

When Ma returned from Aunt Lisa’s funeral, Riann surprised her with HopCat fries and cheese sauce for her birthday. The next morning, Ma went to Mass at St. Charles, chatting with parishioners afterward until Brother Ray started locking doors. She piled Kaden, 11, and London, 6, into the van to go taste-test food samples at Costco.

As she did, the MOL Premium was fresh into its weeks-long journey across the Pacific. The voyage would be at least the sixth body bag shipment to arrive on U.S. shores by sea that month.

***

On Friday, Oct. 25, 2019, the MOL Premium pulled into the Port of Long Beach at 3:45 a.m. About the same time, Ma, three hours ahead in Detroit, texted her daughters on their “Gossip Girls” group chat: “Are you people up?” She made breakfast and headed to work.

The ship berthed at Pier G, just south of the Queen Mary, its hundreds of containers stacked like Jenga blocks across its deck. Crews checked the seal and offloaded container THAF48823 with cranes. It was locked onto a truck bed and driven 33 miles southeast to the Laguna Hills warehouse of Salam International, owned by Abdul Salam, who came to the United States from Karachi, Pakistan, nearly half a century ago.

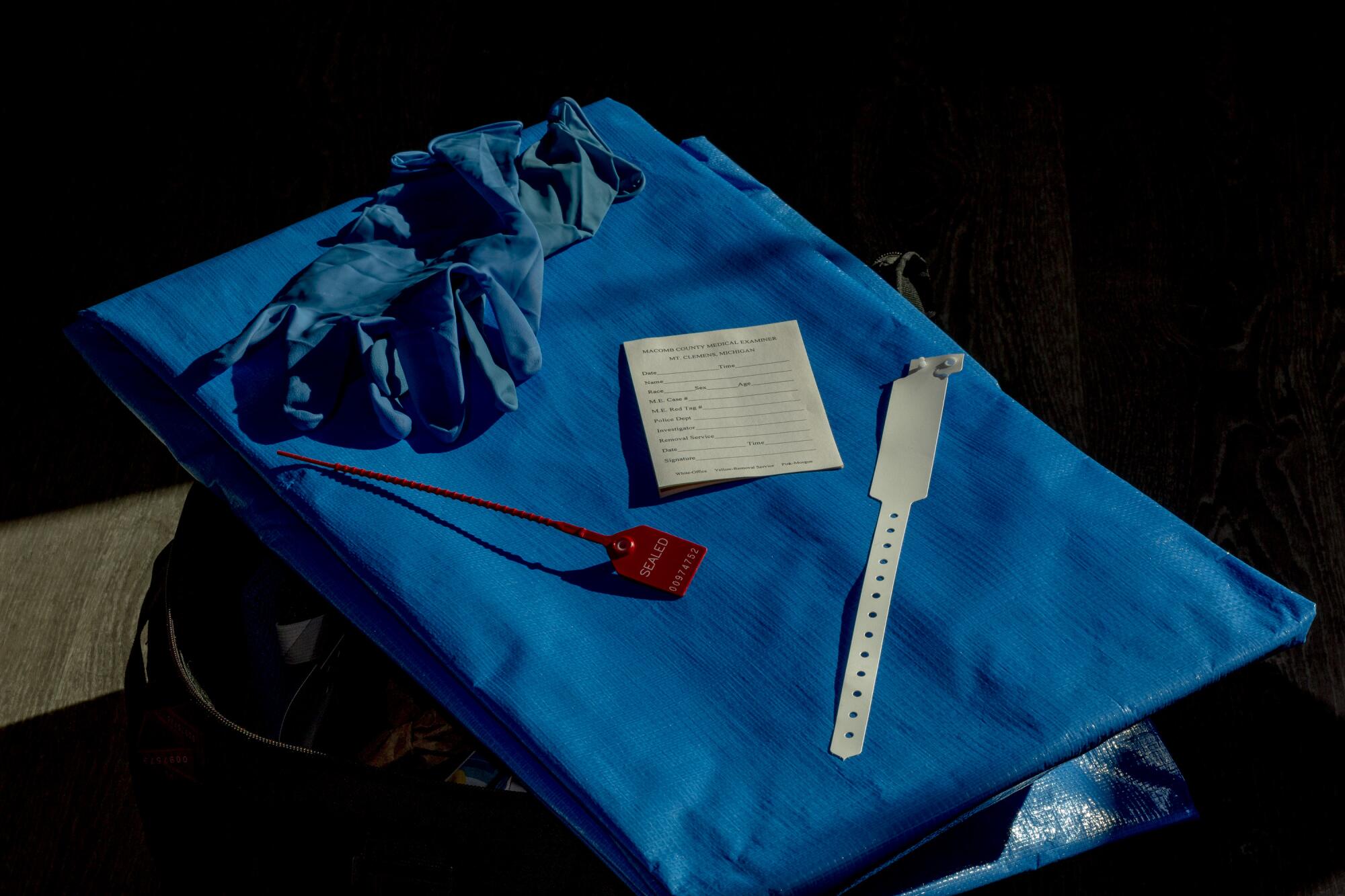

One of the nation’s busiest mortuary suppliers, Salam’s company distributes autopsy tools including stainless-steel skull breakers, toe tags, jaw spreaders and oscillating electric saws, complete with a bone dust collector. The top sellers, by far, are their “disaster pouches.”

The warehouse stocks body bags of every variation: infant, pediatric, adult and jumbo; with and without handles; environmentally friendly bags and heavy-duty water-recovery ones.

A meticulous and sober man, Salam doubled his order of body bags when he learned of the coronavirus in January 2020.

By February, his phone never stopped ringing. By March, walk-ins were showing up at his warehouse. By April, its inventory of 100,000 bags was depleted.

The same month, the Federal Emergency Management Agency requested 100,000 bags from suppliers. The virus was killing so many New Yorkers — more than 33 each hour — that first responders there were fashioning makeshift pouches out of trash bags and tape. Things would only get worse: In June alone, the United States would import 726,176 pounds of body bags — more than seven times the amount it imported during the same period in 2019, according to the trade database Import Genius.

Body bag distributors turned for help to companies that made tents, boat sails and children’s bounce houses. Those that made waterbed mattress bladders, well-versed in sealing vinyl to lock in fluids, were “the perfect fit,” one distributor said.

The virus by late spring had infected 300,000 and killed more than 8,100 Americans. Lost jobs equated to those of the Great Depression and Great Recession combined. President Trump, under fire for initially downplaying the virus, declared that there would be “a lot of death.”

Fresh graves multiplied and even those — like Salam — who were accustomed to such things were overwhelmed.

“I sent bags for September 11th. I sent bags for Hurricane Katrina,” he said. “I had a sixth sense that this one would be more bothersome. We ran out of everything, and the virus didn’t care — it wore on.”

Soon after the container from Thailand arrived at Salam International, 15 cases of product #11-224 were loaded onto pallets and shipped 2,300 miles to the medical examiner’s office in Macomb County, Mich., 25 miles northeast of Detroit. The body bags were expected to last through the following spring.

***

The pandemic spread like a flame through Detroit’s predominately Black population. Already battered by poverty and scarred by abandoned houses, the city, the largest in the U.S. to ever file for bankruptcy, became a landscape of ferried corpses, overburdened hospitals and final goodbyes spoken into phones.

The news was full of reports of ventilators and body counts. Few knew what to do. Infections spread from house to house. It was Granny, Ma’s mom, who appeared sickest on Saturday, April 4. She had diarrhea and couldn’t keep food down. Ma and her daughters held a three-way conference to talk about what to do.

Riann had heard local advisories asking people to not visit emergency rooms “unless it was serious, serious.”

They would wait and see if Granny’s condition took a bad turn. But that night, when Ma came home from work, she was winded just walking from her van to the concrete porch of the family’s one-story brick ranch. Raven asked if it might be coronavirus. Ma looked up from the couch and waved her off.

“If it goes left, it goes left,” she joked. “I’ve made my peace with God.”

They joked that she had to keep her voice to sing “Jessie’s Girl” at karaoke.

By Sunday, Ma couldn’t sleep well; it was painful to lie down. Raven texted Riann: “Ma’s not being honest.”

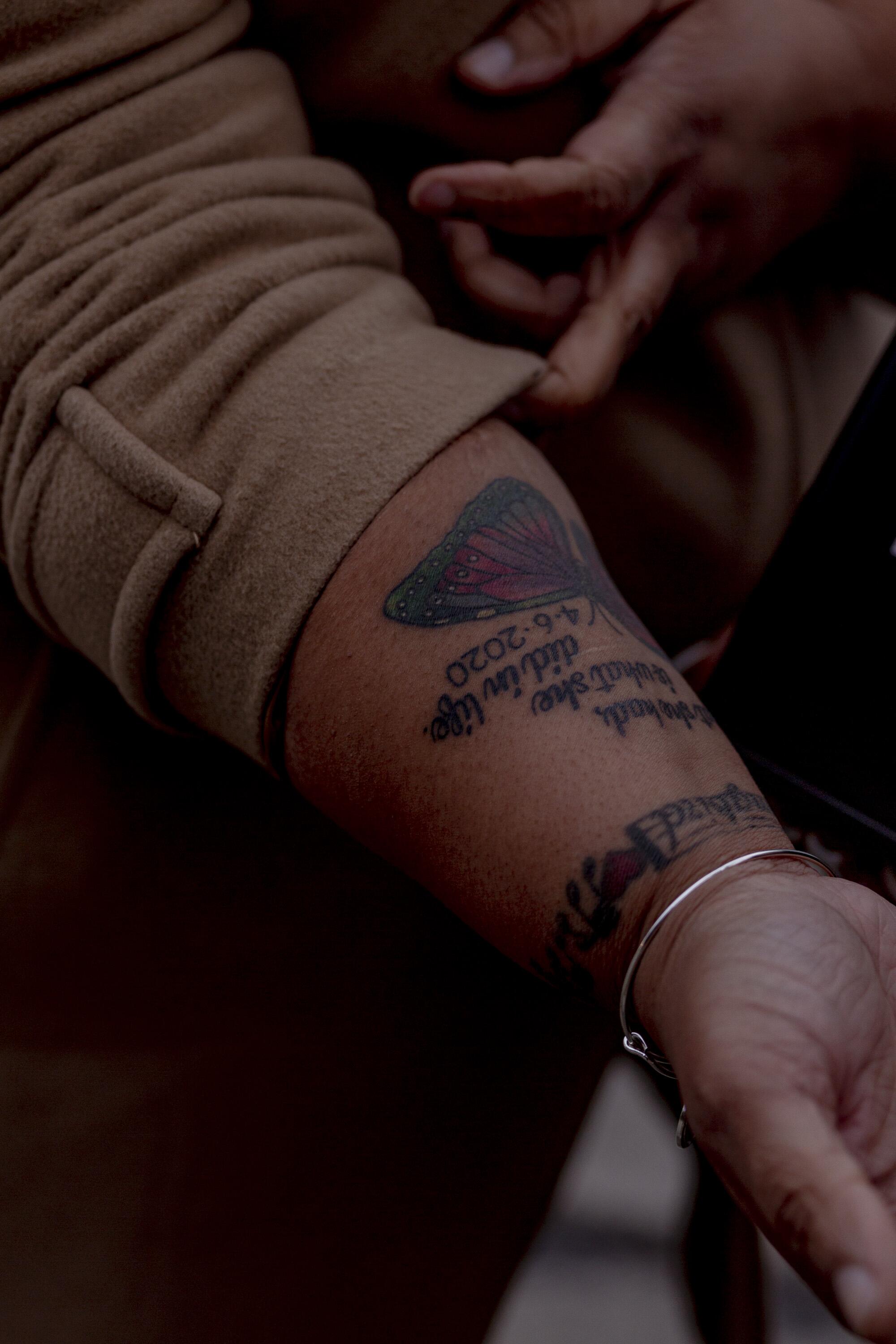

A day later on April 6, Riann drove over, stopping to pick up some broth at a Thai place. Riann asked Ma to come stay at her house, promising Raven would look after the rest of the family. For once, Ma obliged, shuffling around her bedroom to pack some toiletries and change her clothes.

As they waited, Riann and Raven turned on the “Real Housewives of Miami”; the kids played on their iPads. The volume in the living room was a notch too high: No one heard Ma fall.

At 9:50 p.m., Raven went to the bedroom. She couldn’t open the door; Ma was lying against it, only her legs visible through the crack. Raven called out. Riann came running. She squeezed through the door, her left shoe popping off into the hallway.

“No!” she screamed.

“It was like I went back to being a baby,” Riann said, “Calling out to Ma, hoping she’d answer me.”

Raven rolled Ma onto her back and gave her chest compressions.

Kaden called 911. Medics arrived.

It happened like it happened to a lot of others.

Ma was pronounced dead at 10:22 p.m.

***

Gretchen Terebesi, a forensic investigator for Macomb County, got a 10:30 p.m. call from the St. Clair Shores Police Department. She climbed into her department’s Ford Edge and, with a blue body bag in a Rubbermaid storage bin in the cargo space, headed south toward Detroit.

Terebesi, 44, had a long history in criminal justice: first as a correctional officer, then as a crime scene technician, a 911 dispatcher and — for the past 15 years — a death investigator.

House calls were rising steadily that spring. But the virus’ assault on Detroit was only just beginning; sometimes, she would handle multiple cases from the same household, only days apart. Ma would be the first case of Terebesi’s overnight shift.

Terebesi was soft-spoken, with an Alabama accent and auburn hair that brushed her shoulders. She, too, was the mother of two girls. And at 11:25 p.m., she donned a mask and gloves and walked up to the white metal awning of the ranch home.

By then, Riann had kissed her sister and left. Raven was waiting, a friend by her side. Granny kept uttering that her daughter was gone.

“When the medical examiner comes to your home, it’s the worst day of your life,” Terebesi said. “I could see these girls had lost their foundation — their glue.”

Terebesi’s is a job one wants to be quiet, quick and done. She looked over the scene and took photographs. She placed Ma in the blue bag with a label on the outside: Case #1418-20. At 11:50, she called for her transport team, and at 12:55 a.m., Ma arrived at the medical examiner’s office.

She was signed into a log and placed on the examination docket for the next morning. The death certificate was signed on Good Friday: 55-year-old; nonsmoker; no prescription medications; good health. Cause of death: COVID-19 infection and related complications.

The bag was zipped up once more. It would hold Ma until she was cremated.

Family voices rose and met in the days after. Whispered things that make a life. Ma had grown up riding bikes with friends over the Detroit River — from Dorchester Street on the East Side to Belle Isle. Her girls decided that, though Ma would never own a pickup truck, ride on the back of a Harley, or visit Seattle — all unfulfilled dreams — they might one day be ready to grant her final wish: to have her remains scattered on the river.

Anything Ma had ever told them “was Bible,” Riann said.

“And Detroit flowed through her like the river itself.”

***

Nearly 11 months later, tourists no longer flock to the Buddhist temples along the holy river known as Bang Pakong. Now, only grieving families visit to see monks bathe their deceased before cremation.

But every dawn, Winbest Industrial’s floors vibrate under machinery; lighting turns everything blue. The white paint on the sewing needle plates chips away with all the pounding. The handiwork is stacked, crated and shipped. Demand is as high as ever.

Chakpangchaluem, the deputy manager, commutes to the factory from Chonburi, a neighboring province where coronavirus cases are climbing. As a Buddhist, she tries to “put myself into a Zen state” and not think about what’s driving the company’s profit.

Still, she said, even a small cough lifting from the base of her throat brings panic. She walks the floor, her charges stay busy. It will go on this way for some time; the sealing of polyethylene, the fastening of curved zippers and the neat, waiting rows of black, white and blue — and all the hands they’ll pass through on their journeys.

Caleb Quinley in Thailand contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.