- Share via

HAWTHORNE, Fla. — It was still dark when the Rev. Albert Mann stepped outside his trailer home, looked to the sky and prayed for the dying to end.

He climbed into his white pickup — refuge from the Florida mosquitos — as he prepared for his sermon.

“Please, God,” he said. “Let us get out of this pandemic.”

Halfway across the country in North Dakota, Nikole Hoggarth rose before the sun and let out the dog, careful not to wake her husband or the six children who still lived at home. Her nurse’s uniform was laid out in the bathroom.

She grabbed a chocolate shake for the road and set off for the 50-minute drive to the hospital. Country music helped clear her head.

Meanwhile in Houston, the nation’s fourth-largest city, Fire Capt. Daniel Soto reported to Station 16 just outside downtown and pointed an electronic thermometer at his temple.

Ninety-nine — high enough to send him home under the department’s coronavirus precautions.

He took his temperature again and passed.

So began Nov. 22, a Sunday, exactly 307 days since the first coronavirus case was diagnosed in the United States.

The nation’s death toll stood at 257,117 — more than drug overdoses, breast cancer, suicide and diabetes combined for any recent year. Only heart disease, the nation’s leading cause of death, kills more people.

The first surge of infections came in late March and stretched into April. The virus spiked again in June and July.

Now a third surge was setting records for infections, with more than a million new cases reported each week.

Even with years of experience dealing with death, Mann, Hoggarth and Soto struggled to fathom the meaning of those statistics. Not that there was much time to think about the numbers while working on the front lines.

::

Gordon Chapel Community Church, a white building with blue stained glass, was a block down the street from where Mann lived.

As the 63-year-old reverend arrived, he noticed that somebody had smashed part of the picket fence. He knew there were people in Hawthorne — his tiny town just outside Gainesville — who hated him for what happened.

What happened was that Mann had trusted his faith.

For months, even as other churches closed, he kept the doors open. The choir sang, Sunday school met, and the elderly gathered weekly for Bible study.

Then the virus came like a wave. Even though they wore masks in church, more than half of the 100 people who came to pray each week became infected.

The virus left his wife bedridden for more than a week. It killed her mother, a brother, an aunt and an uncle.

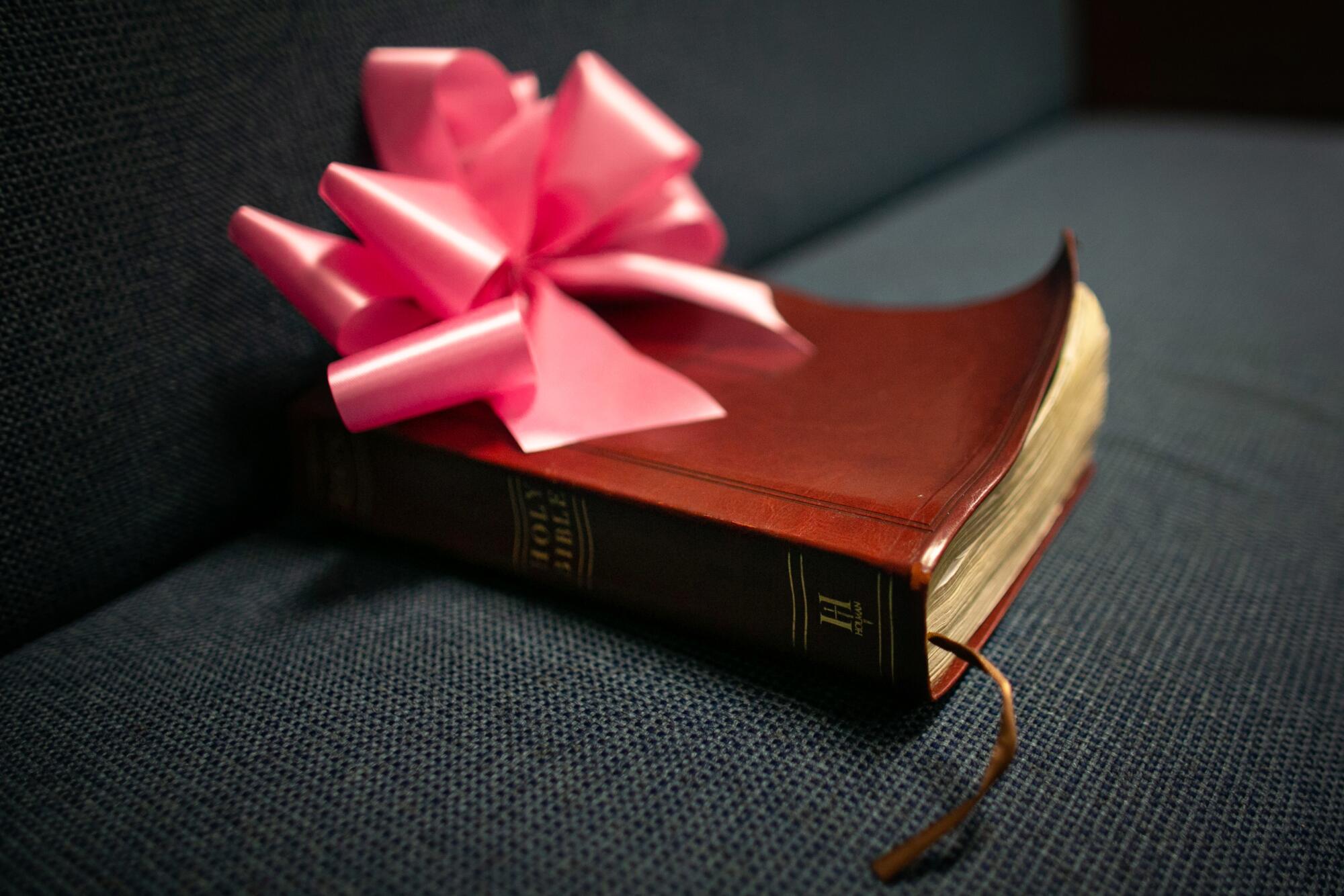

Mann opened the front door and said a prayer. A pink bow and a Bible marked the pew where his mother-in-law, Ella Cuthbert, used to sit.

In walked her sister, 78-year-old Charlene McDonald, back for the first time since getting sick.

“My kids would be so mad if they knew I was here,” she told Mann. “But God is too good.”

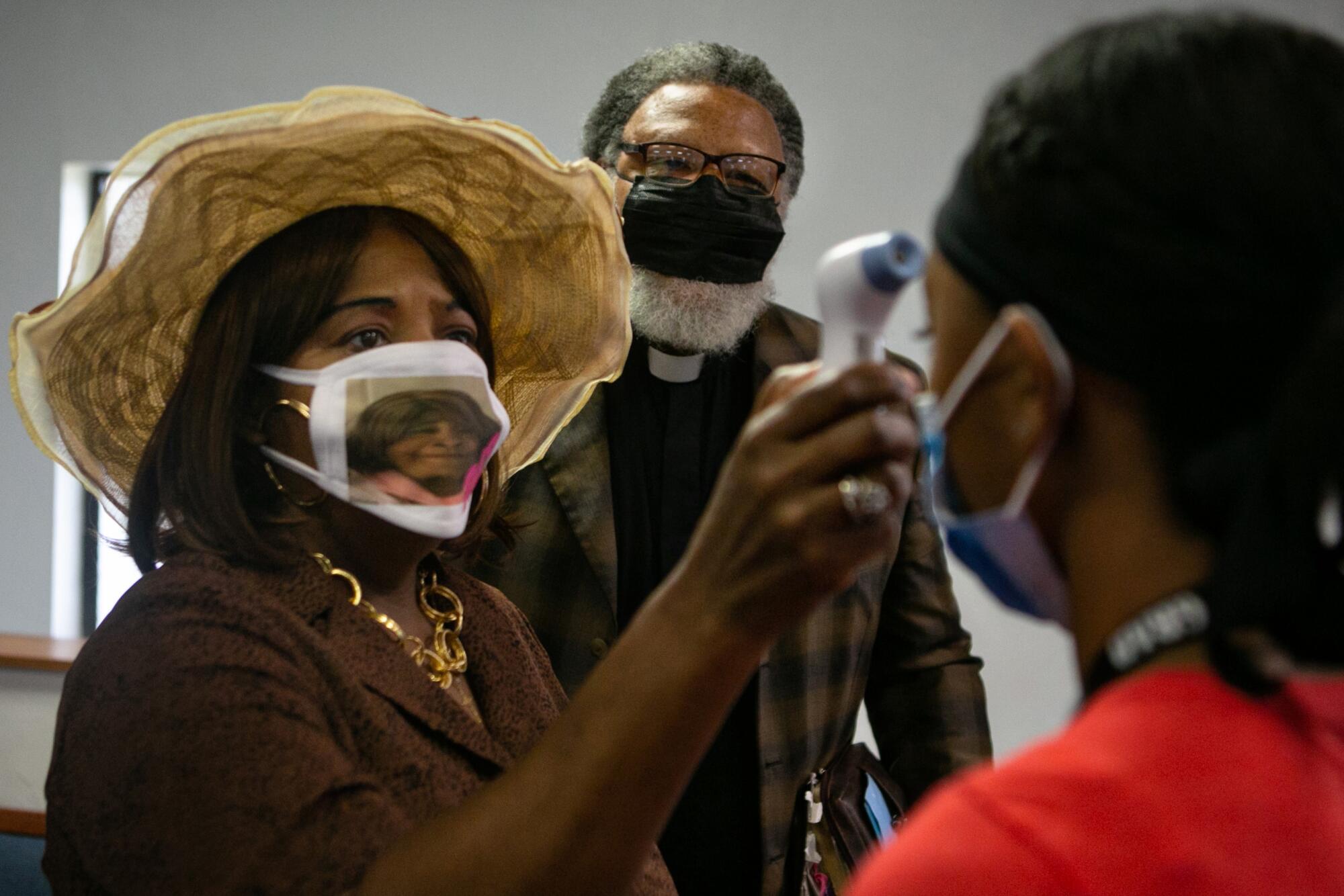

Second to arrive was Valencia Jenkins-Mann, the pastor’s wife. She wore a mask with “R.I.P.” on a print of her mother’s face.

“I’m so happy to see you Aunty,” she told McDonald. “That virus got me good.”

::

It was 9 a.m. when paramedics blew through double doors at the Jamestown Regional Medical Center emergency room with a stretcher and swung left into Room 7.

The patient was in her 80s and struggling to breathe.

Hoggarth donned a yellow gown, tugging on white sleeves and wincing from back pain as she reached behind her neck to tie a knot. She pulled a respirator hood over her brown, pixie-cut hair.

“Another COVID coming in a private car,” a receptionist called out as Hoggarth disappeared into Room 7.

Back in March and April, Hoggarth had scrolled through Facebook posts by big-city frontline health workers who described losing three or four patients a shift — a “horror story,” she called it.

Now that story had come to her emergency room in North Dakota — which suddenly had the highest rate of new infections.

Exhausted by consecutive shifts, she resented people who ignored warnings and continued gathering for birthdays, weddings and anniversaries, spreading the virus and filling her 25-bed hospital.

Hoggarth hooked up monitors in Room 7 as Dr. Steve Inglish started his examination.

“Dehydrated,” he said, dictating his observations into a recorder. “Diarrhea, according to caretaker. I gave her 500 milliliters of intravenous fluid.”

The woman had 87% oxygen saturation, low enough that it once would have meant admission to the hospital.

But Inglish and Hoggarth had treated enough coronavirus patients to learn that they could send her home with oxygen and steroids as long as the hospital continued to closely monitor her during video calls.

Every hospital bed was precious.

::

At 7:30 a.m. sharp, the intercom at Station 16 blared out an urgent call: “Your food is getting cold!”

Soto sat down at the long wooden dining table with the other 10 firefighters — all men — for a breakfast of sausage and bacon sandwiches with hash browns. A Waylon Jennings tune wafted from a portable speaker.

As a 35-year-old supervisor and paramedic, Soto worked in 24-hour shifts, rushing to 911 calls to oversee serious medical emergencies or assist less experienced firefighters.

He was also responsible for protecting his co-workers from the virus. Some were skeptical about whether it was much of a threat, even though it had killed three members of the department.

The normal emergencies — car accidents, drug overdoses, heart attacks — didn’t stop because there happened to be a pandemic.

Dispatchers used to ask 911 callers about possible exposure to the virus. But as it spread, they stopped inquiring about symptoms, and responders began treating everybody as if they were infected.

After breakfast, one of Soto’s fellow captains did roll call and reminded his men to wear their protective gear on every call. One firefighter realized he didn’t have a mask on and pulled his shirt up over his nose and mouth.

It had been a slow morning. Soto knew those rarely lasted.

::

The reverend slipped on a white collar, walked to the lectern and removed his mask to speak.

“Good morning, good morning! We’re coming live from Gordon Chapel Community Church.”

He had been broadcasting services on Facebook since things had gotten bad. Only a dozen people — all immediate family — attended in person.

At 6-foot-3 with a bushy white beard and black glasses, Mann towered over them in his brown-and-black checkered suit.

Ten minutes into the service, Mann asked for volunteers to sing. McDonald obliged, choosing a tune on the healing power of Jesus.

You know that Jesus is my doctor.

You know that he writes out all my prescriptions.

You know that he gave me all my medicine.

The pastor opened his King James Bible to John 9:3, a lesson on God’s role in suffering and sin, he explained, building toward his conclusion.

“Even with the pandemic that is going on, God is still in control,” he shouted.

Mann preached about his vision to hold the church together in a time when it could so easily fall apart. God, he said, “called just who he wanted but he left you and me here.”

It had been just a day since he presided over back-to-back funerals for his wife’s brother and aunt.

::

Nearly nine hours into her shift, Hoggarth had barely eaten.

Patients had been arriving non-stop. The emergency department had run out of exam rooms and started instructing possible coronavirus patients to wait in their cars.

Hoggarth, who at 47 had her own health issues, including high cholesterol, glanced at the pedometer on her wrist. Already five miles for the day.

“Can I grab that ankle injury and put him in the conference room?” a voice called out. It was Inglish.

Between coronavirus cases, the emergency room crew also treated a woman who was bit by cat, a wife who said her husband had hit her, and a 2-year-old who had fallen off the tailgate of a pickup and needed stitches in her forehead.

Hoggarth darted out to the reception desk: “Can you quick call that guy who left? I didn’t give him his meds.”

The sun had set when 75-year-old Verdell Jacob hobbled into Room 7.

Hoggarth recognized him right away — one of the many coronavirus patients who responded well to treatment, then relapsed.

A retired butcher, he spoke slowly, the result of a stroke seven years ago.

“I got tested Tuesday. I got the result yesterday,” he said. “I can’t taste anything. I’ve got diarrhea. Acid stomach. If I sleep in my bed, I can’t breathe. I’ve been sleeping in the recliner.”

“You’ve always got a smile on your face,” she told him.

“And crying on the inside,” he said.

::

His siren blaring, Soto sped down Texas Interstate 45, weaving through traffic.

It was 3:40 p.m. as he pulled up to firefighters performing CPR on a man face-up on in the middle of the right lane. He had been hit by a driver who witnesses said stopped to take his wallet.

Before joining his team, Soto paused to slip on an N95 mask, surgical gown and gloves.

The man’s ribs were crushed. Firefighters loaded him into the ambulance, and Soto climbed in behind him. He guessed the man was probably dead, but his team had to keep trying.

As the ambulance sped down the highway, Soto noticed something was off. Two firefighters trying to resuscitate the man weren’t wearing all their protective gear. Soto instructed them to gown up and monitor themselves for symptoms in coming days.

At the hospital, a team checked for vital signs. Soto had been right: The man was dead.

“I’m calling it – 4:01 p.m.,” a doctor said.

Soto found a sink to wash his hands.

As he walked out of the hospital, he crossed paths with a sheriff’s deputy entering with a man in handcuffs and no mask. The man sneezed.

There was nothing Soto could do about it.

::

Back at home, Mann sunk into his living room recliner and turned the television to the Steelers-Jaguars game.

Neither squad was his team — he favored the Cowboys — but in a life upended, Sunday football was comforting.

He felt guilty for enjoying himself when there was still so much pain. He pressed pause on the remote, grabbed his phone and stepped outside on to the wooden patio.

First he called to check in on Mary Smother, an 80-year-old who had started coming to Gordon Chapel after her church closed — only to come down with the virus. Finally feeling better, she asked Mann about coming back to church the next Sunday.

“Hold off just a little,” he told her.

Then he called Delores Fisher, in her 60s, who said she felt like she was “going to die” when she was sick. She, too, hoped to return soon.

Mann went back inside, feeling better about finishing up the game. He even managed to cheer a little.

The Steelers won 27-3.

::

Hoggarth’s 12-hour shift was ending as paramedics wheeled a coronavirus patient out the double doors and into an ambulance.

She had treated him days earlier in the emergency room, before he was admitted to the hospital with severe breathing problems.

Now Jamestown Regional Medical Center had done all it could for him. The ambulance departed on a 100-mile trip east to a bigger hospital, in Fargo.

Hoggarth had the look of a woman who had seen miracles in Room 7 yet had little hope for one this time. It was the same expression she wore after treating the domestic abuse victim.

She planned to keep an eye out for his name in the obituary section of the Jamestown Sun.

::

It was 9:54 p.m. when firefighters requested Soto’s help with a 67-year-old woman who had fallen in her home.

Neighbors had found her on the floor two days later, guarded by her pit bull. Now she was refusing to go to the hospital.

As Soto drove to the house, he passed packed open-air bars and nightclubs full of patrons without masks. One restaurant had posted a sign: “Give me liberty or give me corona!”

Soto didn’t think shutdowns were the only solution to stopping the spread of the virus. But he saw a straight line from packed clubs to the chance that he would contract the virus on the job and pass it to his wife and their 4-year-old daughter and baby son.

He’d been lucky so far. But his 68-year-old uncle, who had been skeptical that the virus posed much threat, had become infected and died.

Soto arrived at Judith Cooper’s house to find her sitting in her living room in her underwear and no mask, arguing with two firefighters about whether she needed medical help.

They helped her get dressed and loaded her on a stretcher and into the ambulance. Soto held her hand.

“I am so glad you are letting us take you to the hospital,” he said.

She thanked him, tears welling in her eyes.

But after the ambulance sped off, Cooper was soon upset again. “I didn’t bring a facial mask!” she cried.

A firefighter handed her one.

::

Sunday, Nov. 22, ended as it began — with America in a state of mourning and uncertainty and ordinary people living for the promise of something better.

In Florida, Mann got on his knees before bed, praying for the church as it readied for the first week fully open again — with freshly scrubbed pews and distancing markers.

In North Dakota, Hoggarth took a shower as soon as she arrived home, threw her uniform in the washing machine and only then — after she had done everything she could to minimize the chances of transmission — hugged her husband.

In Texas, Soto drove back to the station, showered and retired to a bedroom — the only place at the station he spent extended periods without a mask.

There was nothing particularly special about Sunday, Nov. 22. It was just another day in the pandemic.

Kaleem reported from Hawthorne, Fla., Hennessy-Fiske from Houston and Read from Jamestown, N.D. Times staff writer Emily Baumgaertner contributed reporting from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.