A jailed Philippine activist is forced to attend her infant’s funeral in handcuffs and a hazmat suit

- Share via

MANILA — The infant girl lay in a white coffin adorned with purple and yellow flowers, a ceramic bunny and pink slippers.

Her name was River. She was born into poverty, the daughter of Reina Mae Nasino, a 23-year-old activist in one of Manila’s most desperate slums, who was arrested last year as part of the Philippine government’s relentless crackdown on human rights workers.

River was separated shortly after birth from her jailed, nursing mother. She died of pneumonia this month in the care of her grandmother. Her plight and the handling of her funeral last week have ignited outrage in the Philippines, a country where conditions for human rights defenders have deteriorated under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Nasino was given six hours to leave jail to attend River’s wake and burial in a Manila cemetery after a judge denied her request for a three-day furlough.

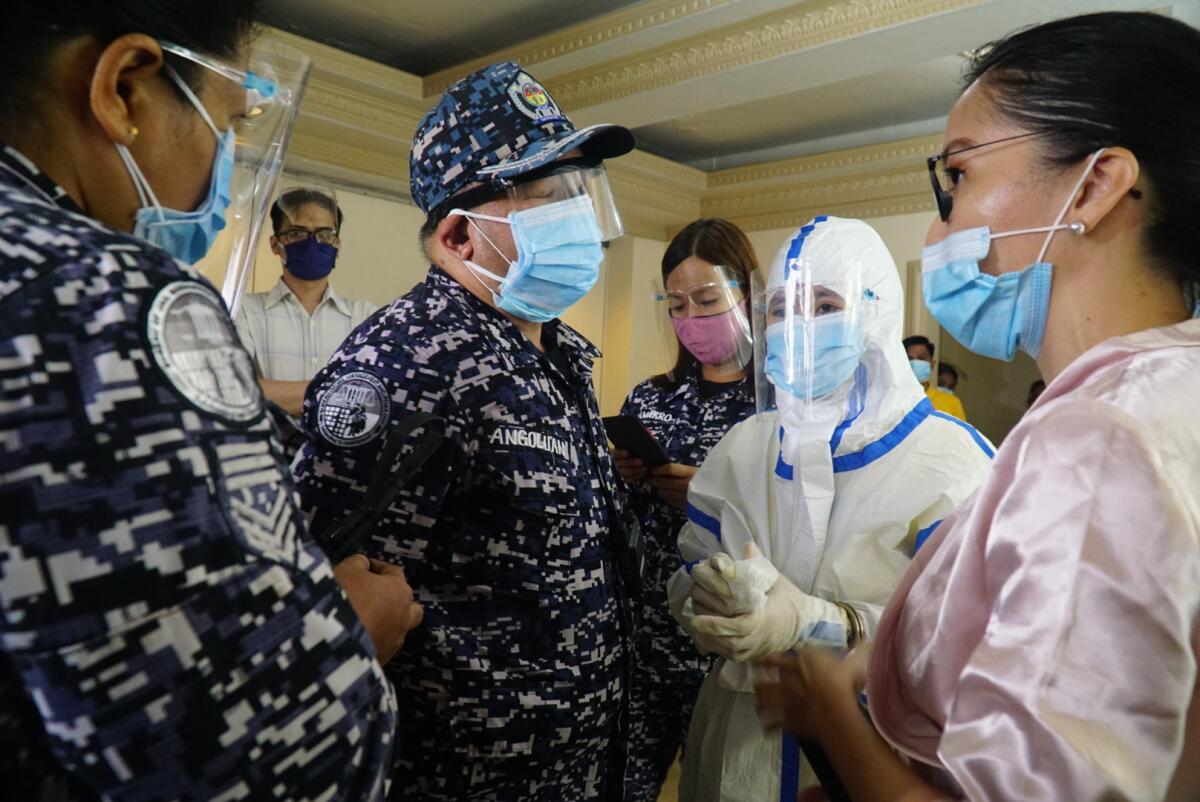

In images that have drawn charges of cruelty from rights advocates and celebrities alike, Nasino was forced to attend River’s wake handcuffed and swathed in a hazmat suit because of coronavirus concerns in the country’s prisons. More than three dozen uniformed prison guards, many armed with automatic rifles, surrounded her.

“We were denied the chance to be together,” Nasino could be heard saying through her face shield while sobbing over her daughter’s coffin. “I didn’t even see your laughter. I will be freed and I will leave the jail as a stronger person.”

Nasino struggled to wipe away tears after requests to remove her handcuffs were denied. When she began answering questions from reporters inside the funeral home, prison guards tried to drag her away. Lawyers and family tried to pull her back. A tug of war ensued.

“The circumstances are ridiculous,” said Josa Deinla, one of Nasino’s lawyers. “They’re worried Nasino will be ‘rescued.’ Why would a mother run away from a chance to bury her child?”

Xavier Solda, the spokesman of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, defended Nasino’s treatment, saying she was a flight risk. He blamed the “left” for using the wake to create a “spectacle.”

On Monday, a spokesman for Duterte said the president “respected” the actions taken by prison officials to secure River’s funeral ceremonies.

But the treatment of the grieving mother drew the attention of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights, which said it was investigating Nasino’s case for evidence of political imprisonment. The organization also expressed concern for the way River was separated from her mother, a possible violation of United Nations standards for the treatment of female prisoners, known as the Bangkok Rules.

Nasino had asked to be held at a hospital or prison nursery for River’s first year, but her request was denied by a judge who said the jail lacked the resources, according to her lawyers.

Zara Alvarez was at least the 90th victim of an extrajudicial killing on the Philippine island of Negros under the Duterte administration.

Nasino was arrested in November along with two other activists and charged with unlawful possession of firearms and explosives, a non-bailable offense. Nasino and her supporters say the evidence was planted because of her affiliation with Kadamay, an anti-poverty group that clashed with authorities in 2017 after members occupied a public housing project north of Manila built for the poor that was being claimed by soldiers and police. Duterte had warned the group that its members would be shot for resisting arrest.

Dissent in the Philippines has been violently suppressed by the 75-year-old president, who has made activists and civil society advocates the frequent target of extrajudicial killings by labeling them terrorists and communists.

At least 248 human rights workers, journalists, lawyers and trade unionists have been killed during his administration, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

“President Duterte has empowered the police’s impunity, not only to the accountability to the law, but also to basic human decency,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch.

Nasino’s rejected bid for a three-day furlough has highlighted inequities in the penal system, her supporters say. Well-connected politicians such as former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who was charged with corruption, was twice given multiple days away from detention to celebrate Christmas, New Year’s and her birthday.

“Cruel, degrading and inhumane treatment is being heaped upon Reina Mae Nasino, especially if one compares it to the treatment of VIPs who were charged and in prison,” said Cristina Palabay, the Manila-based secretary general of Karapatan, a human rights group. “This is because of the state’s labeling of activists like Nasino as ‘enemies’ or ‘terrorists.’”

A court initially granted Nasino three days to visit her deceased daughter starting Oct. 14 up to the scheduled burial Friday. But the decision was reversed after officials from Manila City Jail said they didn’t have enough staffers to guard Nasino for three days. The facility’s female dormitory houses nearly four times the population it was designed for, according to court records.

Nasino has been at the jail since February, shortly after she learned she was pregnant. Her supporters say she was denied adequate prenatal care.

River was born in July — underweight at 5.5 pounds. A doctor told Nasino to breastfeed her. Despite that, a court ordered Nasino and River separated a month later. Prosecutors had argued that Nasino’s supplemental use of formula was evidence the infant did not need breastfeeding.

Ressa’s conviction was seen as a severe blow to press freedom in the Philippines under strongman President Rodrigo Duterte.

River was turned over to Nasino’s mother, Marites Asis, on Aug. 13. It was the last time Nasino saw her daughter. Visitation rights for detainees had been suspended since March to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The infant girl was diagnosed with pneumonia less than six weeks later and admitted to an intensive care unit at Philippine General Hospital. By Oct. 9, she was dead. A laywer called Nasino in jail to share the news.

“Both of them just cried and cried,” Deinla said. “I don’t know how long the conversation lasted because they were just crying.”

Nasino has returned to Manila City Jail, where she’s in quarantine for 21 days instead of the regular 14. Her lawyers are unsure why. They worry about her mental health in isolation.

“She was hopeful she would be reunited with River once she’s free,” Deinla said. “But that will never happen.”

Times staff writer Pierson reported from Singapore and special correspondent Balagtas See from Manila.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.