Lezmond Mitchell, the only Native American on federal death row, is executed

- Share via

TERRE HAUTE, Ind. — The only Native American on federal death row was put to death Wednesday, despite objections from many Navajo leaders who had urged President Trump to halt the execution on the grounds it would violate tribal culture and sovereignty.

With the execution of Lezmond Mitchell for the grisly slayings of a 9-year-old and her grandmother, the federal government under the pro-death-penalty president has now carried out more executions in 2020 than it had in the previous 56 years combined.

Mitchell, 38, expressed no remorse during the public portion of the execution. Asked by a prison official if he had any last words for victims’ family members and other witnesses behind glass at the death chamber, Mitchell casually responded, “No, I’m good.”

Moments later, prison officials began the lethal injection of pentobarbital that flowed to IVs in his hands and forearms in the tiny, pale-green death chamber at the federal prison in Terre Haute, Ind.

Mitchell lay strapped down on his back, his glasses still on and a medical mask across his face, never moving or tilting his head to look around the room. His chest heaved and his thumb tapped the gurney momentarily, as his breathing became labored and his stomach area began to throb. After about 10 minutes, Mitchell no longer appeared to move at all and his partially tattooed hands turned pale.

An official with a stethoscope checked for a pulse and listened to Mitchell’s heart before he was declared dead at 6:29 p.m. EDT. It took nearly 30 minutes for him to die.

Mitchell, then 20, and an accomplice were convicted of killing Tiffany Lee and 63-year-old Alyce Slim after the grandmother offered them a lift as they hitchhiked on the Arizona portion of the Navajo Nation in 2001. They stabbed Slim 33 times, slit Tiffany’s throat and stoned her to death. They later mutilated both bodies.

A bid by tribal leaders to persuade Trump to commute Mitchell’s sentence to life in prison failed, as did last-minute appeals by his lawyers for a stay. The first three federal executions in 17 years went ahead in July after similar legal maneuvers failed. Keith Nelson, who was also convicted of killing a child, is slated to die Friday.

Lawyers for Nelson argue the drug used in the executions, pentobarbital, can cause severe pain and should be deemed unconstitutional.

Tiffany Lee’s older brother and her father thanked Trump for moving forward with the execution and have criticized the opposition by tribal officials.

“They will have to answer to God why they wanted this murderer to live,” the brother, Donel Lee, told the Associated Press. “But now I’m at peace with it and justice is served. Now he [Mitchell] has to answer to God, and I hope my little sister was standing there with God while he judged him.”

Tiffany’s father, Daniel Lee, witnessed the execution. He stood in tears shortly after, wearing a Trump campaign hat, and said in a statement that Mitchell’s death brought him some long-awaited closure.

Critics have accused the Trump administration of pushing to resume executions after a nearly 20-year hiatus in a quest to claim the mantle of law-and-order candidate. Mitchell’s execution occurred during the GOP’s convention week.

In a statement, Mitchell’s lawyers said the execution “added another chapter to its long history of injustices against Native American people.”

The Federal Death Penalty Act allows tribes to decide whether to subject their citizens to capital punishment for a set of major crimes involving Native Americans on Native land. Nearly all, including the Navajo Nation, have said no. The Justice Department charged Mitchell with carjacking resulting in death, which fell outside that provision of the law.

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez offered prayers Wednesday to both the victims’ and Mitchell’s families.

He blasted the federal government for ignoring the tribe’s decision to not accept the death penalty.

“We don’t expect federal officials to understand our strongly held traditions of clan relationship, keeping harmony in our communities, and holding life sacred,” he said in a statement. “What we do expect, no, what we demand, is respect for our People, for our Tribal Nation, and we will not be pushed aside any longer.”

Carl Slater was among Navajo leaders hopeful Mitchell’s sentence would be reduced to life in prison. Navajo culture teaches that all life is sacred.

“I’m incredibly fearful for all the relationships between Indian Country and the U.S. government, that this will set the precedent that any voice our governments give to our people and our collective citizens will be disregarded, ignored,” Slater said after Mitchell died. “And, ultimately, the federal government will do whatever it pleases to Indian peoples.”

Death-penalty advocates say the Trump administration’s restart of executions brings justice to victims and families. One woman and 58 men currently are on death row. Many of their executions have been pending for over 20 years.

“Nearly 19 years after Lezmond Mitchell brutally ended the lives of two people, destroying the lives of many others, justice finally has been served,” Justice Department spokesperson Kerri Kupec said in a statement.

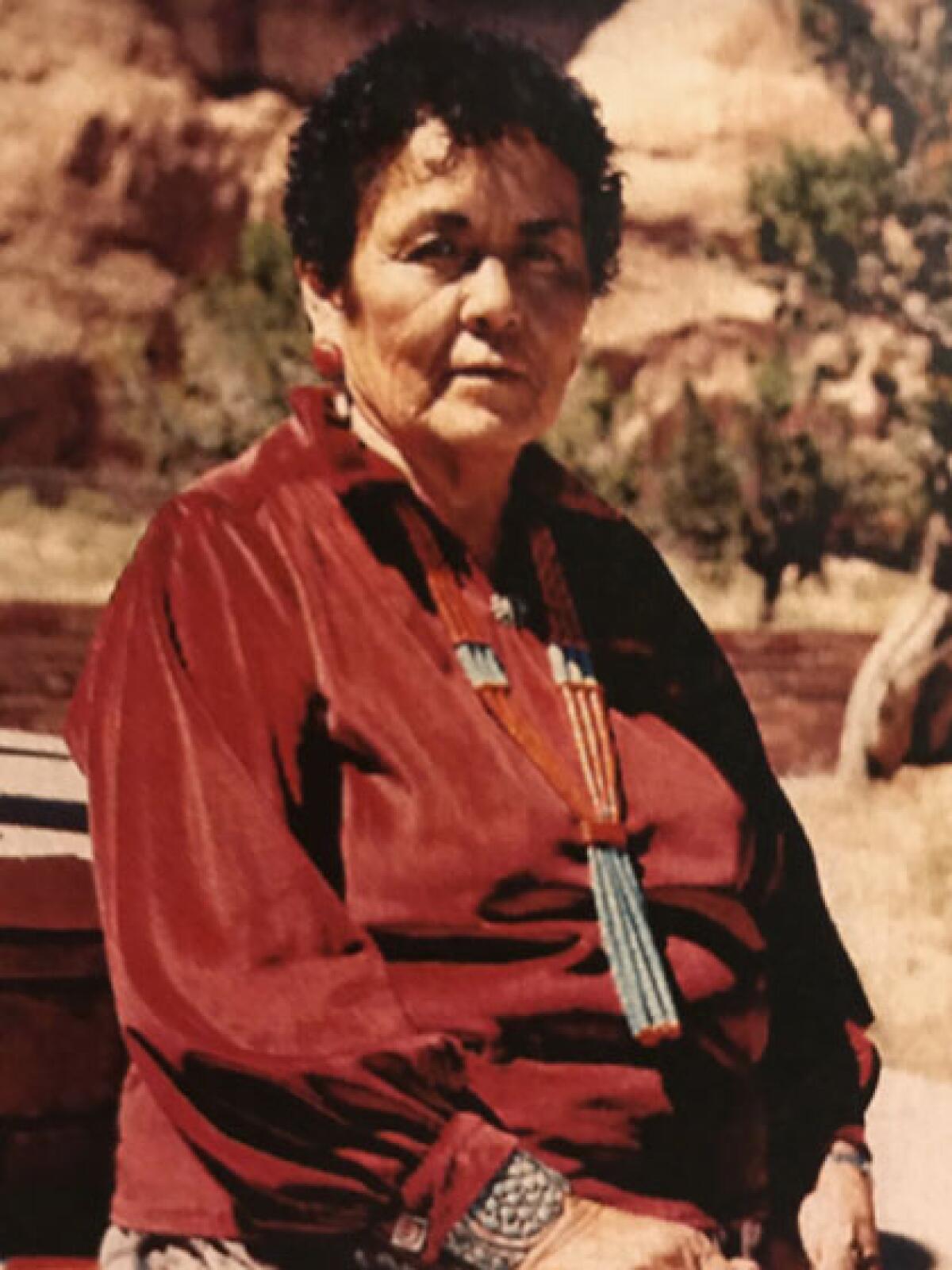

Family and friends described Slim, a school bus driver who was approaching retirement, as gracious, spiritual and well-liked by students on her route.

Attorneys representing some of Slim’s family — including her daughter and Tiffany’s mother, Marlene — said they supported the execution. Marlene Slim spoke against capital punishment at the time of sentencing.

Michael Slim, the grandson and cousin of the victims, is an outlier. Once an advocate of death penalty in the case, he gradually changed his mind and said it should be left up to God.

“We are all guilty of sin, so it’s not fair for us to condemn someone,” he said this week. “It’s not my job to say ‘we should kill him.’ ”

Mitchell has long maintained that his accomplice, Johnny Orsinger, took the lead in the killings. Orsinger was a juvenile then and couldn’t be sentenced to death. He’s serving a life sentence in Atlanta.

Mitchell, through his attorneys, said he wanted to participate in a traditional way of resolving disputes known as peacemaking that’s meant to restore harmony and balance. But he was not allowed to contact victims’ families under a court order.

Auska Mitchell, Mitchell’s uncle on his maternal side, said he had been praying and burning cedar earlier Wednesday and was heartbroken to hear his nephew died.

“I hope he gets the peace in death that he didn’t get in life,” he said. “It can’t be peaceful being on death row and probably solitary all the time. That’s no life to live.”

None of Mitchell’s family attended the execution.

Among several anti-death-penalty protesters at an intersection across the street from the prison was Sister Barbara Battista, who is serving a spiritual advisor to Nelson as he awaits execution.

Nelson and Mitchell were friends, having been on death row together for nearly two decades, she said. Both men and other death row inmates haven’t been holding out much hope that their lives will be spared, Battista added.

“They are all pretty resigned,” she said.

Prior to this year, the federal government had carried out just three executions since 1963, all of them between 2001 and 2003, according to the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center. Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was among them.

The first of the resumed executions was of Daniel Lewis Lee on July 14. Two others, Wesley Purkey and Dustin Honken, were executed later the same week. The victims of all three also included children.

The executions of Christopher Andre Vialva and William Emmett LeCroy are scheduled for late September.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.