Hong Kong journalists harassed, arrested and lose press freedoms under new China law

- Share via

HONG KONG — Once known for fierce independence and exposing the misdeeds of the political elite, iCable has had the sting taken out of its reporting as the Chinese Communist Party tightens its grip on this city by arresting journalists and raiding newsrooms.

The broadcaster’s new director of news, Oscar Lee, is best known for being a television anchor and a parenting influencer. He was widely mocked on social media after a recent interview with the police chief, which critics said was overly fawning and deferential.

That is China’s intent as investigative journalists are threatened and top news executives shoved aside. Since the arrest this week of media tycoon Jimmy Lai, founder of Apple Daily, reporters and editors have been hiding their notes, protecting contacts on encrypted messaging apps, and contemplating how much jail time they could get for violating Hong Kong’s new national security law.

“It would probably be three to five years, but if I plead guilty in court and have good conduct, I will likely get a sentence reduction,” said a reporter at Apple Daily surnamed Chan, who declined to use his full name for fear of retribution.

Such are the calculations in a disturbing new era. The chilling scene of Lai’s arrest, which was livestreamed across the world, showed police rummaging through reporters’ desks and shouting at the paper’s chief editor after he asked to see a search warrant. Outside Apple Daily’s offices, police limited media access to only those that backed the mainland Chinese government.

In the stepped-up assault on Hong Kong’s freedoms after a year of pro-democracy protests, the raid on Apple Daily marked a new phase in China’s bid to silence critical reporting in a city with a vibrant history of independent journalism.

Unlike the mainland where media are essentially the propaganda arm of the ruling Chinese Communist Party, the semiautonomous Hong Kong has a commercial news industry, which is guaranteed freedom of press under the city’s constitution.

Those rights have been harder to defend. Since Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997 by Britain, the number of outlets willing to report critically on the local and mainland governments has shrunk under political and economic pressure. Newsrooms are often censored by owners who have business interests in China.

What remains of those independent voices is expected to dwindle even further with the introduction six weeks ago of a national security law that criminalizes dissenting views of Beijing and calls for greater management and regulation of the news business.

Hong Kong’s sizable foreign press corps also faces an uncertain future. Correspondents’ visa requests have been delayed and expectations are growing that Hong Kong will impose the same strict accreditation process used in the mainland.

“The protest movement in Hong Kong would not have had as much international awareness and attention if Hong Kong wasn’t a free and welcoming place for international journalists,” said Gwyneth Ho, a former local television journalist who was recently disqualified from running for Hong Kong’s legislature for opposing the national security law. “If they’re forced out, then the world will not know what will happen next.”

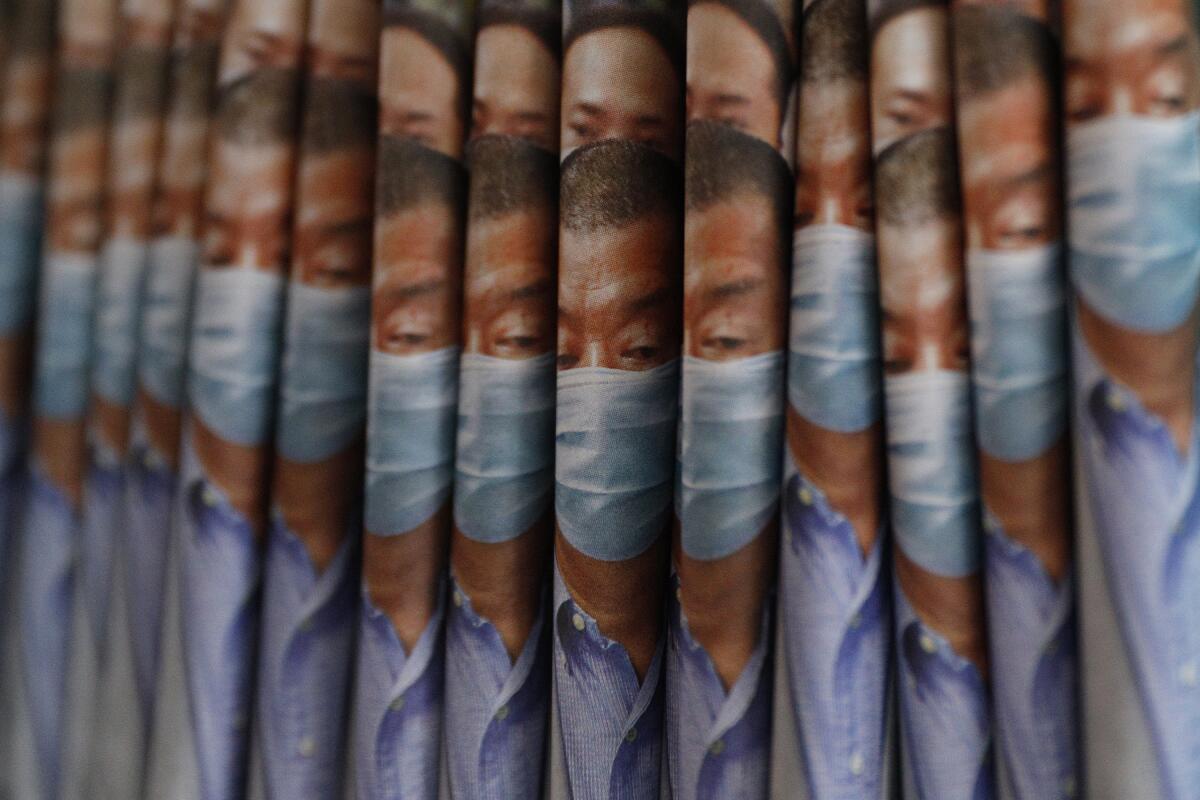

Hong Kong media tycoon Jimmy Lai was arrested alongside his sons and several colleagues at Apple Daily under China’s harsh new national security law.

Locally, few outlets have done more to keep the powerful honest than Apple Daily, which was founded in 1995 by Lai after he made a fortune in the clothing business.

An outspoken critic of the Chinese regime since the deadly crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in 1989, Lai has been labeled by Chinese state media as a “true race traitor” and is accused of colluding with foreign forces by urging the United States to support Hong Kong’s autonomy. He remains free on bail.

“He is a tragedy in which he, as a Chinese, picked the wrong side and walked on the wrong path,” read an editorial in the Global Times after his arrest.

Once known for its sensational headlines, Apple Daily has long irritated authorities for its criticism and investigative reporting, exposing abuse of public funds and shoddy work at public construction projects.

That’s made it a target of the pro-Beijing establishment. Advertising revenue has plummeted in recent years after businesses were pressured to boycott the company. For weeks last year, Hong Kong’s former chief executive, Leung Chun-ying, shamed businesses on social media that placed ads in the paper.

Journalists at the company also have been harassed.

In December, Chan was among 132 staff members who were doxxed and had their personal details — including names, birth dates and photos — exposed online. By tracing the personal data to its source, the paper’s investigative team found that the information was leaked by national security agencies, which have access to data collected by the authorities when reporters applied for mainland travel permits.

In September, a co-worker, who reported on the protests, was assaulted by four masked men while having dinner at a restaurant.

“If you have one to two daring outlets still breaking news, then all the others have to follow,” said Francis Lee, director of the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “You can’t pretend a story’s not out there. It creates a dynamic that ensures sensitive stories still get circulated. That’s the reason why the Chinese government is targeting Apple Daily.”

While the public’s attention was mostly fixed on the purge at Apple Daily, a shake-up was taking place at iCable, where executives were replaced and Oscar Lee was named news director.

Less than two weeks under a new national security law enacted by Beijing, Hong Kong residents already feel a curtain of control falling over the city’s realms of speech and thought.

The sudden turnover is emblematic of the way Chinese authorities have gradually exerted control over local press through behind-the-scenes changes in ownership, personnel appointments and budget cuts.

“The purpose is to control the highest authority in the newsroom and leverage that power to influence the direction and agenda of news coverage,” said Allan Au, a media and political commentator in Hong Kong.

Observers say iCable’s decline began after it was sold in 2017 to investors: real estate moguls Henry Cheng Kar-shun and David Chiu Tat-cheong, both of whom have close business ties with mainland China.

The broadcaster soon diverted resources to focus on business news in mainland China. Sensitive topics started appearing less. Pressure from the owners was felt in the newsroom. Two former staff members said they witnessed the news director receive angry calls from the company’s board, which had never occurred in the past.

During this year’s anniversary of the June 4 crackdown on protesters, an iCable interview with Zhang Xianling, the mother of a 19-year-old who was killed in Tiananmen Square in 1989, was shortened to remove her comments on Hong Kong’s national security law and similarities to restrictions in China.

A New Year’s Eve segment was edited to exclude the chanting of a popular protest slogan by demonstrators: “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our time.” In its place, an editor added the sound of a New Year’s countdown taken from archival footage.

Reporters, some earning a little more than $25,000 a year, started leaving iCable.

“Even if they don’t aggressively censor,” said a reporter who recently left, “we still could not maintain our old journalistic standards because the worsening media environment has led to an exodus of talent.”

Those who have decided to stay face a journalism of limited impact and shrinking freedoms.

“It feels very draining when most of your time is spent on a futile fight resisting the collapse of the institution instead of doing actual journalism,” a reporter at the broadcaster said. “I feel like I am fighting alone. I would also like to leave, but with similar scenes playing out across newsrooms in Hong Kong, where else can I go?”

Some Hong Kongers have supported embattled media companies. Tens of thousands more copies of Apple Daily have been sold than usual this week. Activists briefly pumped up the stock value of the paper’s parent company.

Chan and other journalists at Apple Daily are accustomed to the intensifying battle over telling their stories. He has been pepper-sprayed and struck by tear gas canisters and rubber bullets during street protests.

“In our role, we see a lot of people getting injured and making sacrifices,” he said of the protesters. “They are things they should not have suffered. But at the same time, we have to admit there is nothing we can do to save them and that is where we feel the most powerless.”

Chan spent the hours after the police raid on Apple Daily seated by his colleagues, typing and filing his story before midnight. At 1 a.m., as thousands watched the paper roll off the printing press on a livestream, Chan took deep breaths and tried to check his emotions.

Times staff writer Pierson reported from Singapore and special correspondent Cheung from Hong Kong.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.