- Share via

SEOUL — Lee Duk-hoon’s humble storefront in a hilly neighborhood in Seoul is called Sae Eeyongwon — “New Barbershop.”

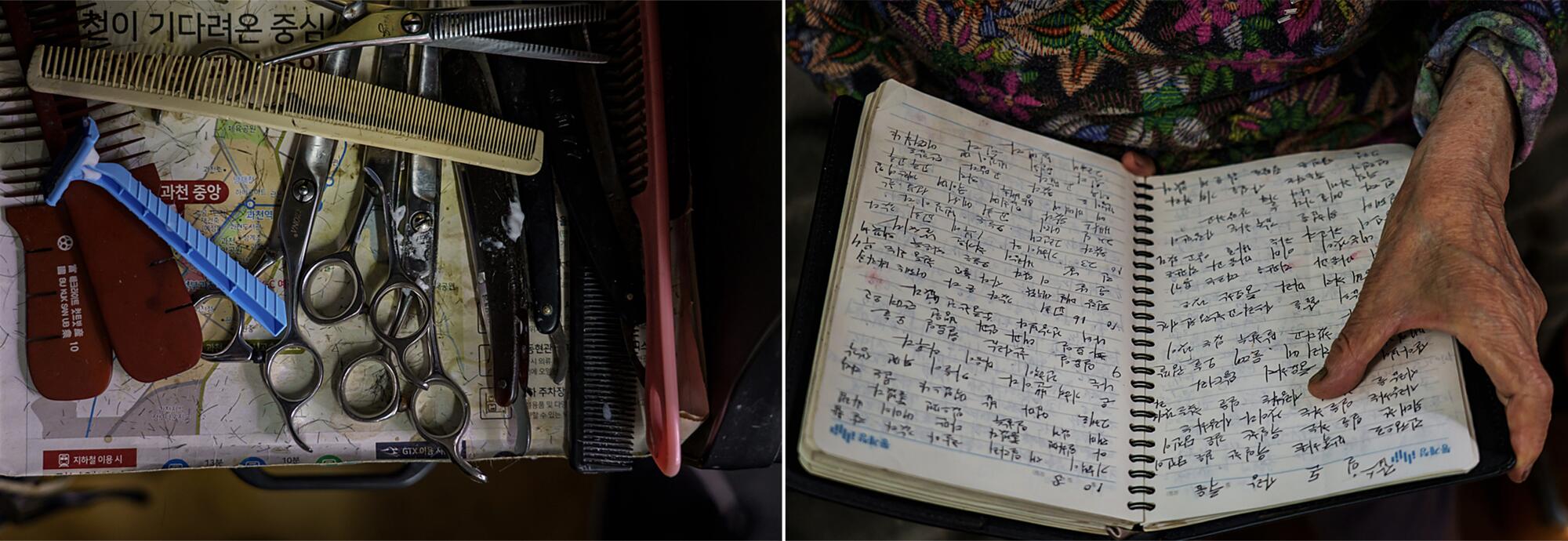

Little about the place is new. The shop opened in 1975. Lee is 85; her barber’s license is from 1958. One of her straight razors — German-made, steel blade — is six decades old, younger than many of her regulars.

She started trimming hair and giving shaves at 19, at a time when women did not work outside the home, much less cut men’s hair. People did double takes at the diminutive, round-faced girl with pigtails snipping hair alongside her barber father in postwar Korea. They seemed bemused when she passed the test to become the first female barber in the country.

Lee never gave much thought to her place as a woman in a man’s world. There were six younger siblings to be clothed, fed and put through school and, later, a husband and four sons to support. Through a dictatorship, a coup, democratization and an economic marvel, through a woman’s rise to president and subsequent impeachment, she continued clipping away.

“No matter how much the world changes, people still need their hair cut,” she said. “If your hair’s a mess, the world is a mess.”

The world, lately, has indeed been a mess.

She and many of her customers were among those most imperiled by the coronavirus that’s upended much of humanity. Half of those who have died in South Korea were 80 or older, despite the fact that they accounted for fewer than 5% of the infected. One in 4 of those infected in her age group died.

At New Barbershop, increasingly ominous newscasts on the TV set filled the quiet between customers in the cluttered one-room quarters where Lee lives and works. Unlike in many other countries, South Korea hasn’t had to close barbershops and other businesses in its fight against the pandemic — as yet.

That could change any moment as the country warily monitors outbreaks cropping up in and around Seoul, averaging about 50 new cases each day in recent weeks.

Throughout it all, Lee coped the only way she knew how — bringing order to a chaotic world one head of hair at a time.

::

The years of wielding scissors have turned her hands knobby and sinewy. So much black hair dye for her graying clientele has seeped into her fingertips and nails, the stains eventually stopped washing off.

Her hands remain as nimble and strong as ever, dancing around a customer’s crown, a snip here, a snip there, flashes in the afternoon light.

Among those who’ve had their hair tamed by Lee over the decades are Hyundai founder Chung Ju-yung, who used to come in for trims, and infamous crime boss Kim Du-han, a mountain of a man with a pockmarked face, who seldom spoke. Several important politicians came and went too, but their names and places in history are a blur.

Kang Ung-kwon, a travel agent, came to Lee on a recent afternoon for his bimonthly cut to unload a bit of hair and a bit of worry.

At 62, he was among her younger customers. His agency, with six employees, had been shuttered since April, with no telling when it’ll start booking trips again.

“It’s rough. My weeks used to be, Mon., Tues., Weds., Thurs., Fri., Fri., Fri.,” he griped, settling into the frayed black leather barber’s chair, as Lee got to work trimming his thick head of hair. “Sat., Sat., Sat., Sat., Sun., Sun., Sun., it turns out, is much harder.”

Kang started coming to Lee about five years ago after his go-to shop near his office closed. Barbershops, along with the generation that grew up going to them regularly, were fast vanishing — most trend-conscious South Korean men these days preferred to get their cuts at swank hair salons.

Seongbuk-gu, the district where Lee lives and works, was once home to more than 300 barbershops; now there are around 80.

“You can’t leave your precious hair to just anybody,” Lee said, draping a yellowing cape around his neck.

Usually, Kang just gets a haircut. But on this day, with the afternoon stretching ahead of him, he also asked for an old-school shave with Gillette foam.

“You haven’t any wrinkles because you have no worries to make you frown,” she told him, lathering his chin. “You must’ve had good parents, and a good wife and children.”

Kang marveled at Lee’s straight razor; the way it gleamed and glided over his cheek.

“People these days don’t know how to use this thing,” he said. “It’s like something out of a Clint Eastwood western.”

::

Lee opens the doors to her shop at 9 a.m. each day and walks out front with still-bleary eyes, scattering puffed rice for a flock of pigeons that have arrived in anticipation of a sidewalk feast.

She neatly combs what’s left of her hair and twirls it into a tidy knot above the nape of her neck, before donning her bug-eye glasses. She dabs on moisturizer and raspberry-colored lipstick, smacking her lips.

Her white barber’s coat — splotched with dye, missing two of three buttons and its too-long sleeves rolled up — will hang on a chair until a customer walks through the doors.

The phone rings. It’s her baby sister — she’s 70 — checking in on her.

“There isn’t a soul on the street because corona’s flared up again,” Lee tells her, talking into a corded landline phone perched atop a stack of books. “Let’s just worry about today. Think about tomorrow when tomorrow comes. When did we ever live comfortably?”

Business had been bad for years before the virus hit. There was a time when Lee would give upward of 50 haircuts in a day. By day’s end, she’d lose feeling in her hands. Demand peaked in the 1970s, when a military dictatorship banned long hair on men as unsanitary and detrimental to social order, and policemen cracked down on those with locks that reached below the ear.

In recent years, she was lucky if she got a half-dozen customers a day.

That was plenty, though, for her to pay her bills and buy food. Her modest prices — 10,000 won, or about $8 for a cut — haven’t budged in more than a decade. For seniors and a neighbor with cerebral palsy, she charges half price.

When a neighborhood man in a tattered hiking jacket hands Lee a 10,000 won bill for his monthly haircut, she stuffs three 1,000 won bills back in his hand. He insists on giving one of them back to her.

The man, who is pushing 70, has been coming since he was in his 20s. She knows full well where the vicissitudes of life have left him, as he does of her.

“I just need my regulars,” Lee said. “It’s not like I’ll be taking anything with me when I go.”

So many have gone ahead. A husband, two sons and two sisters. An infant daughter who wasted away before her first birthday because her mother didn’t have enough to eat to produce milk — whose death she still mourns now, decades later, not having had the time or heart then.

She had to provide for her family; her husband, disabled in a car accident, couldn’t.

And then there were the two others she aborted, fearing they would suffer the same fate in the abject poverty the country suffered in the ruins of war, poorer than North Korea and most developing nations.

And the decades-long customers whose stories stay with her even though they’ve gone, including two she visited regularly on their deathbeds.

“People who started coming at 50 are over 90 now. When they stop coming, I figure, they’re dead,” she said. “They’re more like family than customers.”

::

Four rickety chairs sit in front of Lee’s store, providing a neighborhood rest stop for anyone in need of a pause.

On quiet afternoons, she sits out front, enjoying the breeze, admiring her flowerpots and watching the world go by.

A Rolls-Royce and a Maserati roll past, as does a man lugging a handcart piled high with cardboard boxes for recycling.

Pimply schoolboys in their uniforms with a curtain of hair hanging past their eyebrows walk by in twos and threes. How can they even see ahead with hair like that, she wonders out loud.

A nonagenarian neighbor, in a hat with a flower and purple pants, ambles over with a cane to sit next to Lee, as she does most afternoons. They greet passersby, gossip about neighbors and hum songs from their youth.

The lull between customers has stretched longer and longer of late. The contagion that had seemed close to being stamped out has continued to flare up, increasingly in Seoul and surrounding areas.

She’s known war and poverty far more devastating than this virus, but it seems few others share her perspective.

It’ll take more than a pandemic, though, to pry the scissors out of Lee’s hands.

On a recent morning, a real estate agent looking for new listings cold-called the shop and asked Lee if she had any plans to retire and give up her lease. How much longer was she going to keep working, the agent asked.

“I’m going to do this until I die,” Lee told her. “This is the one thing I know how to do.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.