- Share via

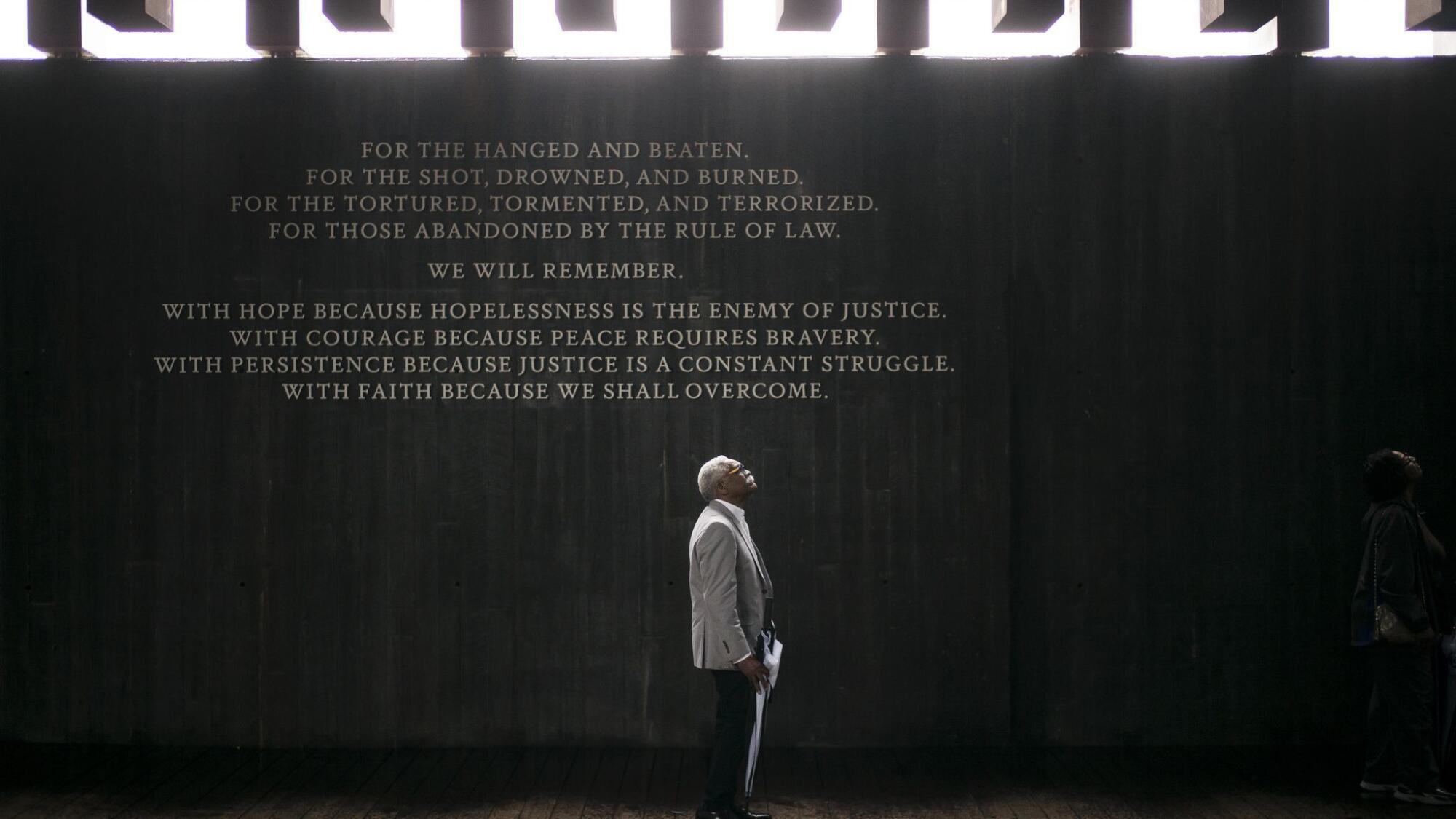

Warren Read searched the crowd for a familiar face. Standing with his friend Virginia Huston, they watched the people emerging from a shuttle in front of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which honors the more than 4,400 Black people lynched in the United States.

The pair had just walked through the Montgomery, Ala., site, their hearts heavy after witnessing the thousands of names of victims inscribed on weathered steel columns. The sky was overcast, and rain seemed likely that opening day in April 2018, but the sky held back its own tears.

Read spotted Mike Tusken, the police chief of Duluth, Minn. The two men had met once before. But it would be Huston’s first time meeting Tusken.

The three of them — two white men and a Black woman — stood on the sidewalk in front of the memorial documenting 400 years of shame, three people inextricably bound together by the actions of their forebears.

Tusken was surprised to see Huston, and she could tell he was nervous. She offered him a smile and embraced him.

The story of how these three people from different parts of the country came together in Montgomery starts on June 15, 1920, in Duluth, a day some residents refer to as the “darkest day” in the city’s history. A day when three innocent Black men were murdered by a violent white mob in front of thousands.

::

The circus was in town on Monday, June 14, 1920, for a one-day stop. There were tightrope walkers and performing elephants under colorful tents in Duluth, a town set on the shores of Lake Superior. It was, and remains, mostly white, and at the time it was on the rise, thanks to its port city status.

A young white woman, a west Duluthian, attended the circus with a friend. Both would later say that they were attacked by Black circus workers. She said she had been raped.

The next morning, a doctor examined the woman and found no evidence she had been sexually assaulted. Nonetheless, six Black men were arrested and jailed, despite a lack of evidence tying them to the alleged crime.

Many of the town’s white residents were incensed over the accusations of sexual assault. Sometime after 7 p.m., a mob used bricks, timber and steel saws to break into the jail and dragged three of the men out.

A mock trial was staged, and Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie were proclaimed guilty. The three, all in their early 20s, were beaten and taken up a hill to 1st Street, where they were lynched on a lamppost.

According to the Duluth Herald, Jackson was calm and threw dice into the crowd, saying he wouldn’t need them anymore. Clayton and McGhie, the newspaper reported, begged for mercy. But for Clayton, who had to watch the other two men die first, there was none.

The mob that killed them was responding to accusations made by 19-year-old Irene Tusken, who was Mike Tusken’s great-aunt. Louis Dondino, Read’s great-grandfather, helped round up residents to witness the killings. Elmer Jackson was Huston’s distant cousin.

Some believe as many as 10,000 people watched the lynching, about a tenth of the city’s population at the time. There appeared to be no shame on the part of those involved. Someone captured the gruesome act with a camera and put the image on a postcard. In the photo, the lynched men are bare-chested, two of them hanging by their necks, the third sprawled on the ground. White faces smile back as the spectators jockey for position, looking right into the camera.

The event rocked the state of Minnesota, a place that many believed did not harbor racist sentiments that defined white Southern culture. The Minneapolis Journal said the mob put “an effaceable stain on the name of Minnesota.” One Black Duluthian wrote that the city “has suffered a horrible disgrace, a blot on its name that it can never outlive.”

But after it happened, the town’s white residents seemed to suffer from “collective amnesia,” author Michael Fedo wrote in “The Lynchings in Duluth,” a book that was published in 1979. The events of June 15, 1920, were hardly taught or spoken about until a local writer, Heidi Bakk-Hansen, published a piece in 2000 that detailed the lynchings and their impact. The article named Irene Tusken, for the first time, as the accuser.

Soon after, residents established Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial Inc., a nonprofit dedicated to promoting racial justice, healing and reconciliation, and in 2003, they debuted a monument at the site of the lynching. Inscribed at the top is a quote: “An event has happened, upon which it is difficult to speak and impossible to remain silent.”

Monday was the centennial of the lynching, and local organizers planned an event they had hoped would draw as many, or more, people than the size of the white mob 100 years earlier. The event was postponed to 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic, but protests against police brutality continue nationwide, even in Duluth, where 2.4% of the population is Black.

They are protesting deaths in Louisville and Atlanta. They are demanding investigations into the deaths of black men found hanging from trees. And on Juneteenth, they are protesting the death of George Floyd, a Black man who was killed by a white police officer 150 miles south of Duluth.

To some, these deaths are a sign that not much has changed, that Black Americans are still fighting for the right to live.

Virginia Huston, 75, was born in Pennytown, Mo., a township in the middle of the state founded by Joe Penny, a former slave who paid $160 for eight acres of land in 1871.

Huston grew up in nearby Marshall, the oldest of five children. (She’d been told that her cousin Elmer had worked for a circus, she recalled in a recent interview, but she knew almost nothing about the man, who died 24 years before she was born.) She attended a black-only school until seventh grade, when schools were integrated. After high school, she worked in cosmetology, retail and then banking, where she worked until she retired.

To this day, Huston maintains the remaining church in Pennytown, just as her mother did before her. And she is helping to organize next year’s celebration of the township’s 150th anniversary.

It was her ties to Pennytown — Elmer Jackson was born there as well— that led Warren Read to Huston in 2005, when he began searching for family members of the lynching victims.

Read, 53, an associate high school principal, lived across the country in Kingston, Wash. In 2001, he began looking into his family’s roots after he and his husband adopted their first son. What he found was a painful story his family had never spoken about.

It was his great-grandfather Louis Dondino who drove a truck around the town of Duluth on June 15, 1920, and rounded up residents to attend what some in the crowd were calling “a necktie party.”

Dondino began on the west end of Duluth and loaded his truck with passengers. He made a stop at a hardware store, where someone picked up the ropes used to hang the three men. Witnesses at the time saw Dondino in the crowd, and later he was one of three white men convicted of inciting a riot. He served about a year in state prison.

“It was shocking. Right away I thought, ‘This is ugly,’” said Read, who described his sense of shame for his great-grandfather’s role in the deaths of the three men.

Dondino was an alcoholic, Read said, but had been close to his granddaughter, Read’s mother. The discovery of his family’s history prompted a painful series of conversations with his mother about recognizing Dondino’s life not just as an admired grandfather, but as a man who had been intimately involved in the lynching of Black men.

In 2005, Read reached out to Huston in an effort to learn more about Jackson, and she received him warmly. They kept in touch and became close. She mailed him acorns from trees in Pennytown, and Read planted them in his backyard. Together, they planted an oak tree near the grave sites of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie in Duluth in June 2008 for the anniversary of the lynchings.

Getting to know Huston, Read said, has helped him acknowledge his family’s ties to the lynchings and better understand that the problems of racial injustice persist.

“It’s not like this stuff is suddenly happening again,” he said, drawing parallels between the 1920 lynching and modern-day killings of Black people. “It’s the fact that we have cameras and witnesses not willing to be silent.”

::

In Montgomery on April 26, 2018, Tusken said he wasn’t sure what to say to Huston, knowing his family had caused hers so much pain.

Tusken had been working in the Duluth Police Department in 2000 when his mother called to let him know the article by Bakk-Hansen was about to be published, and it would name his great-aunt Irene as the woman whose unsubstantiated accusation led to the lynching.

“It was like getting punched in the gut,” he said. “It was devastating.”

Tusken is a Duluth native, and says no one had ever mentioned his great-aunt’s role in the tragic events of 1920. She was the matriarch of his family, Tusken said, and while he never knew what she’d done, he wondered how many other Duluthians were aware of his family’s history.

Some years later, when he was in the running to become police chief, some community members raised questions about whether the actions of his great aunt made him “not a suitable candidate” for chief, he recalled. He issued a public apology on behalf of his family for Irene Tusken’s actions.

More recently, he spoke in support of pardoning of Max Mason, one of the circus workers initially swept up by the local police. After the lynchings Mason was arrested and convicted of raping Irene Tusken.

He was released from prison in 1925, and he died in 1942. His was the first ever posthumous pardon granted by the Minnesota Board of Pardons.

Tusken, 51, says he’s struggling with what is happening now, in Minnesota and the world. He is quick to denounce Floyd’s death, calling it a murder. And he recognizes the systematic oppression of people of color. But he is struggling with the nationwide outrage directed toward police departments and the demands that law enforcement institutions be defunded.

For Huston, there are similarities between the killings of Black men and women by police today and the lynchings of 1920; not much has changed. Still, as she watches the people marching in the street, she sees a reason to be optimistic.

“I know it might not change in my lifetime, but we have the young people; they are stepping up,” she said. “As long as they can keep doing that, the change will come. I think the world will be better.”

But there is no tidy ending to the story that started on June 15, 1920.

Huston, Read and Tusken have all kept in touch and remain friends, and will likely reconvene for the postponed commemoration next year. The city of Duluth has officially apologized for the horrific events and continues to honor the three men who were killed.

But the anguished recognition of a 100-year-old injustice amplifies the calls for justice in the killing of George Floyd and so many others.

Despite the pandemic, on Monday hundreds of people showed up at the memorial downtown to honor the centennial of the Duluth lynchings, including Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and state Atty. Gen. Keith Ellison, both Democrats. Those who attended placed flowers at the feet of the bronze statues of the men who were murdered.

That same day, the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial organization, in collaboration with a local multimedia company, debuted a documentary about what the past 100 years have brought, and how little has changed. It’s titled, “I Can’t Breathe.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.