- Share via

EAGAN, Minn. — Growing up in a shack surrounded by piney woods and tobacco fields in eastern North Carolina, George Floyd’s aunt Angela Harrelson was taught by her sharecropper parents how to get along in a slowly desegregating America: Sit at the back of the bus, do what white folks tell you, “stay strong and hold on.”

That’s what she did when she boarded the local school bus in the 1970s and white students blocked the seats with their feet, making her stand in the aisle. The bus driver, also white, would swerve and threaten to slap black students if they fell. Some days, he wouldn’t pick her up at all.

“But we held on,” Harrelson said as she sat at her kitchen table this week in a Minneapolis suburb.

The abuse only stopped, she said, when a white girl boarded the bus one day and declared, “My mama said this is wrong. Stop picking on them.”

“She was brave because she stood up against her own,” recalled Harrelson, 58. “It takes one person to make a change, speaking up.”

That’s what she sees happening now across the nation and the world as protests spread in the wake of her nephew’s death at the hands of police. The tragedy stirred memories for Harrelson of the legacy of segregation, slights and stinging prejudice her family has endured.

She hopes the four police officers charged in the case, including former officer Derek Chauvin, 44, who is accused of murder, will face justice from a government that has allowed white people to discriminate against African Americans for generations.

Floyd — who the family called by his middle name, Perry — moved to Minneapolis three years ago to be closer to Harrelson and to build a new life. An unmarried father of three, Floyd, 46, wanted to escape the low-income Houston neighborhood where he grew up. Harrelson promised his mother that she would look after him.

“They lived in a tough environment, so he said he was coming to make a fresh start and she was happy,” Harrelson recalled. He took a job as a bouncer and a retail clerk; he got engaged and, although he was 6-feet, 7-inches tall, he still had maturing to do.

A year after he arrived, Floyd’s mother died, and Harrelson felt even more responsible for him. They met a couple times and FaceTimed often. As her parents had done with her, she warned her nephew about dealing with the white establishment, specifically police. She drew her advice from experience.

Her great-grandfather, Hillary Thomas Stewart, was a slave. He got his freedom at age 8, and settled near Goldsboro, N.C. By age 21, Stewart had accumulated 500 acres of land and married a woman named Larcenia, who would bear him 22 children.

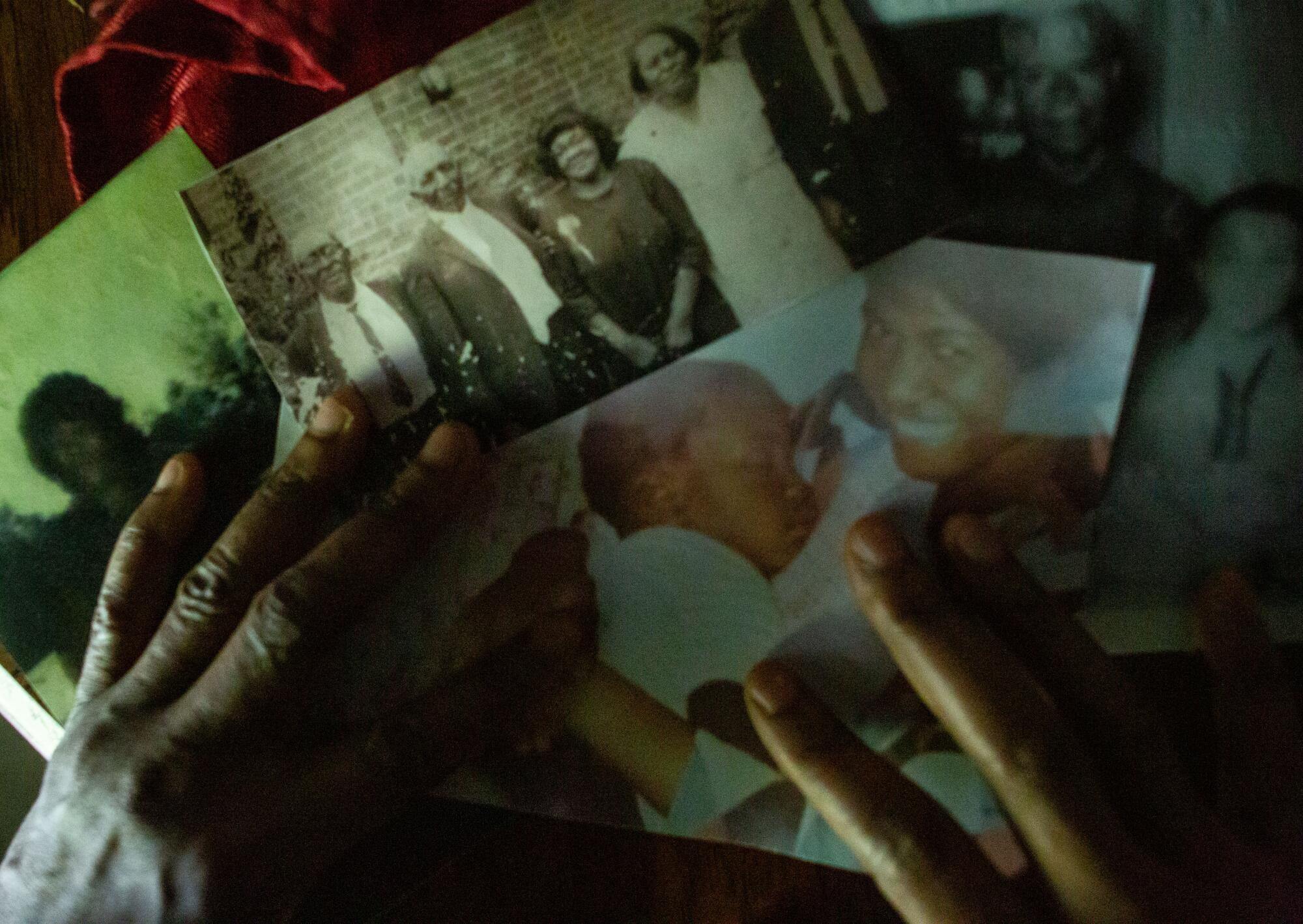

In black-and-white family photos, Stewart poses with his wife in front of a china cabinet full of crockery, wearing a dress shirt and suspenders.

“He did the best he could to build a legacy for us,” Harrelson said.

But the couple couldn’t read or write. White farmers settled their land; they were powerless to fight back.

“It was stolen from them,” Harrelson said.

A Black man’s journey to Houston for George Floyd.

Her grandmother Sophell Suggs cleaned white families’ homes during segregation. She told Harrelson stories about how she had to enter through the back door; how the women wouldn’t give her gloves even to wash their soiled menstrual rags. One of Harrelson’s earliest memories is passing a water fountain labeled “whites only.”

Her mother, Laura Stewart Jones, worked the tobacco fields for $2.50 a day. Sometimes the white farmers refused to pay. Her father, who served in the U.S. Army in Korea and worked at a barbecue on the side, would get upset at being cheated, and they would have to move to another shack without indoor plumbing.

Jones had become pregnant with the first of 14 children at age 13, but taught herself to read, write and play piano. Harrelson was the youngest of her 10 daughters, all of whom graduated from high school.

But Harrelson had grander plans. She worked the tobacco fields during high school, became head cheerleader and won a local beauty pageant. After graduation, she left to attend community college in Iowa where she hoped to become a lawyer. She enlisted in the Army reserves, then the Navy reserves to pay for school.

One day, a professor called her into his office. She couldn’t become a lawyer, he said, she couldn’t even take law classes. He wouldn’t teach her because she was black. Harrelson decided to study psychology instead, then become a registered nurse and Air Force Reserve officer. Officials told her she couldn’t. She ignored them.

By 1998, she had received her commission as a captain in the reserves, married a flight attendant and was looking for jobs when a potential employer urged her to move to Minneapolis. There was plenty of work for nurses, and as tall and pretty as she was, she modeled in her spare time.

Soon after settling in Eagan, an inner suburb where racism was often hidden in “Minnesota nice,” Harrelson went to get her hair done at the J.C. Penney salon in a local mall. She saw they had products to wash and condition black hair, but their sole black stylist was off, and the white stylist refused.

Harrelson sat down in the salon chair.

“I was like Rosa Parks,” she said, laughing. “I said, ‘I’m not getting out of this chair. I’m not trying to make a statement, I just don’t want to drive to north Minneapolis.’”

The white stylist phoned her black co-worker, who explained the procedures. Afterward, the white woman said she had been nervous because she’d never styled black hair.

“You weren’t comfortable because I’m black,” Harrelson said. “Let’s call it what it is.”

The woman agreed.

Harrelson has learned to avoid getting into the elevator at her apartment complex late at night if a white woman is already on, because she’ll inevitably jump or clench her purse in fear. If she’s stopped by police, she responds to their commands in ultra-slow motion, narrating her every move.

After the police stopped her nephew last week, she watched the bystander’s video of police restraining him and wished she had been there to rush in and turn him on his side to clear his airway so he would never have had to utter what were among his last words: “I can’t breathe.”

“He could only fight with his words. He was fighting for his life with his words, and nobody would listen,” she said.

She chafed at prosecutors’ delays, at the release of an autopsy that initially failed to label his death a homicide — until after the family’s lawyer released results of their independent autopsy this week.

“If we didn’t have an attorney, if we didn’t have a second autopsy, what do you think would have happened?” she said.

Harrelson has considered leaving Minneapolis, but she plans to stay until the cases against the officers charged with killing him are resolved. There’s a memorial for her nephew in Minneapolis on Thursday, and his funeral to attend in Houston next Tuesday. She worries about white supremacists targeting the events, but said, “I want to see this through.”

Before her nephew’s death, she felt people didn’t want to talk about racism even in progressive cities like Minneapolis. Now, she’s encouraged that there’s a conversation about it across the country.

“What happened to George changed people’s hearts,” she said; got them talking about the history of not just police brutality, but also the very inequities in education, employment and housing her family has faced.

“That’s a huge start, because you can’t do something if you don’t acknowledge it,” Harrelson said. “They just say you’re playing the race card; that happened 400 years ago. But it’s systematic racism.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.