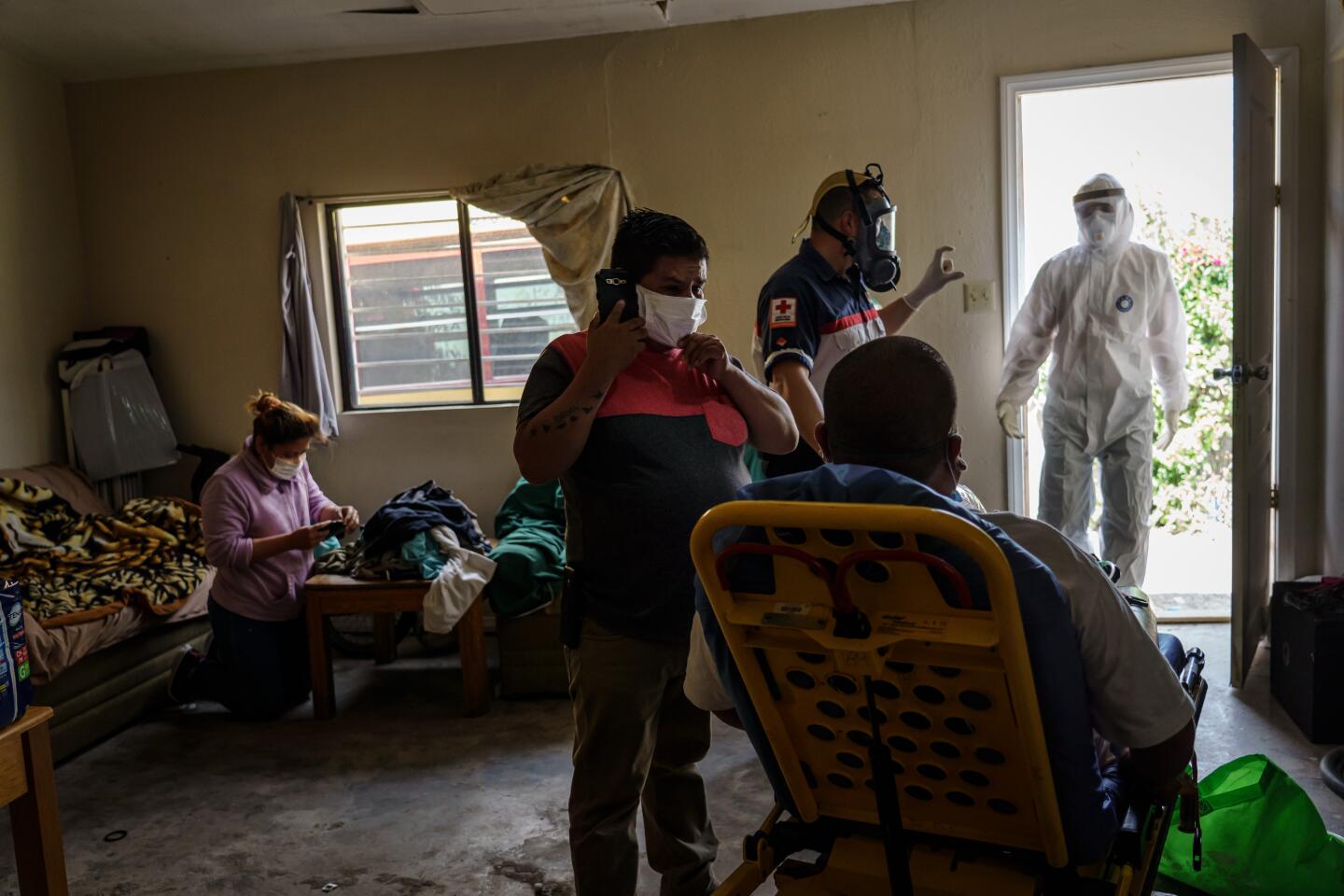

In Tijuana, paramedics uncover a hidden death toll not captured in COVID-19 statistics

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — Researchers who reviewed emergency response records in Tijuana have discovered scores of possible coronavirus deaths that never made it into official statistics.

Over four weeks in April and May, paramedics encountered 329 people who died in their homes or in ambulances — more than twice the number that would be expected based on data from recent years.

Over the same period, the Mexican government reported just eight official COVID-19 deaths in Tijuana that occurred outside hospitals.

The study — which was published online this week by researchers at UCLA, Mexico’s Red Cross and several other institutions and has not been peer-reviewed — suggests the country may be missing large numbers of coronavirus victims in its official counts.

Most of the COVID-19 deaths tallied by officials occur in hospitals — whereas many people who die at home are buried without ever being tested for the disease.

The question of how many people are dying of COVID-19 in Mexico has sparked a heated debate, with government critics complaining that the country lacks a clear picture of a growing crisis.

In cities across Mexico, morgues are full and funeral homes are jammed but nobody knows for sure how many people have died in the COVID-19 pandemic.

In parts of the nation, hospitals are nearing capacity and funeral homes are struggling to keep up — anecdotal evidence that suggests the official confirmed death toll of 6,510 is too low.

Government authorities have acknowledged that some deaths are not counted because they have not been confirmed by tests, which have been in short supply.

In other countries, researchers have estimated the true toll by looking at deaths of all types during the pandemic and comparing that figure to the totals during the same months in previous years.

That approach has not been possible in Mexico, because the country has a two-year lag time in publishing data on deaths.

The authors of the new study realized there was another data source that might begin to help them answer key questions.

The Tijuana Red Cross, which handles 99% of emergency calls in the industrial border city of 1.8 million, maintains detailed logs of its activity.

In mid-April, it saw a spike in the number of people who had died in their homes, according to Dr. Eva Tovar Hirashima, medical director for the organization’s team of paramedics.

The rescuers also noticed an increase in patients with respiratory symptoms and with very low oxygen rates, she said.

Researchers began analyzing 911 data, basing their methodology on an academic study carried out in Italy’s Lombardy region during the coronavirus outbreak there. That report found that at-home deaths had increased by 58% during the peak of the epidemic.

In Tijuana, the researchers looked at at-home deaths as well as those in ambulances between April 14 and May 11 and then compared this year to the previous five years.

Excluding deaths that occurred in accidents, homicides or other forms of trauma, the average for those past years was 135 — or 95 fewer than in 2020.

When the researchers examined the data for the months of January and February, they saw no significant differences between 2020 and past years.

By mapping where most in-home deaths were occurring, researchers found that the rates of people dying at home were highest in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Many of Mexico’s border factories are flouting orders to suspend operations, worsening the spread of the coronavirus.

The authors of the study shared their data with Baja California health officials, who responded by opening a new clinic in Mariano Matamoros, a neighborhood on the eastern edge of the city that saw the biggest increase in deaths compared with previous years. Primary care doctors at the clinic have been instructed to look closely at blood oxygen levels, which are an important indicator of COVID-19.

It’s unclear to what degree the results of the Tijuana study can be applied to the rest of Mexico.

Data analyzed by The Times showed that 10% of the country’s confirmed COVID-19 deaths occurred outside a hospital. That figure in Tijuana during the period of the study was just 3% — or 8 out of 262 officially confirmed deaths.

Still, Joseph Friedman, a medical student at UCLA who worked on the report, said he hopes the model will be expanded across Mexico and to other countries with low levels of testing and poor data collection.

“There’s not great mortality data for Latin America, but all kinds of cities could be doing this analysis,” he said. “This is something that could be done with EMS data any place that has electronic files.”

Brandon Brown, an epidemiologist at UC Riverside who was not involved in the study, said tracking emergency calls is one of the best techniques available.

“With the lack of reliable surveillance data for COVID-19 deaths in many locations across the world, estimating mortality with EMS data may be the best indicator we have right now for the excess deaths caused by the pandemic,” he said.

Tovar said Mexico needs rapid information about the true toll of COVID-19 to help officials make decisions about social distancing measures and how to best deploy doctors and nurses.

“In a country with a health system this fragile, you have to know overall deaths,” she said.

The study did not try to determine the cause of the extra deaths. But Red Cross data made clear that Tijuana is in the grips of the pandemic.

During the study period, paramedics responded to 321 patients suffering respiratory symptoms, compared with the 86 that would be expected based on previous years’ data. Blood oxygen levels for those patients averaged 78% this year, far worse than the 2019 average of 90%.

Many of the efforts to track COVID-19 deaths in Mexico have been anecdotal, and based on reviews of death certificates.

This week, a nonprofit anti-corruption group said it found 4,577 cases in Mexico City in which death certificates linked the coronavirus to fatalities between March 18 and May 12. The analysis counted cases where the disease was not confirmed but was described as a probable or likely cause.

The official number of confirmed and suspected COVID-19 deaths in Mexico City during that period was 1,060 — less than a quarter of the cases cited in the report.

The debate over data comes as the government begin a gradual reopening of the economy.

As of this week, municipalities where few or no coronavirus cases have been confirmed are allowed to resume commerce, school and other activities. And several major industries, including auto manufacturing and mining, that have been declared essential have been given the green light to reopen.

Juan Carlos Mendez, EMS chief for the Tijuana Red Cross, said his teams have responded to fewer patients who died in their homes over the last week compared with the weeks included in the study.

But that does not mean residents should ignore social distancing measures, he said. “We can’t let our guard down.”

Times staff writer Ryan Menezes in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.