Trump calls for ‘war’ on drug cartels after 9 Americans killed in Mexico

- Share via

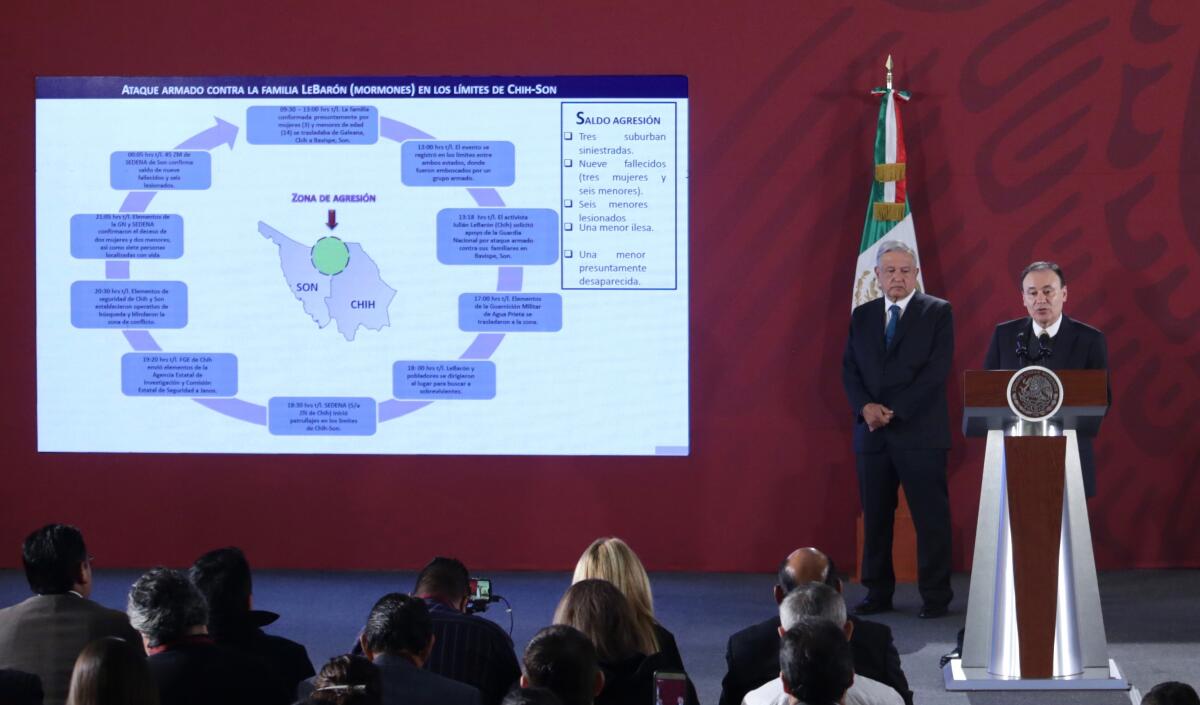

MEXICO CITY — Nine U.S. citizens were killed Monday when their vehicles were ambushed by gunmen in northern Mexico, a brutal attack that prompted President Trump to call for a “war” against Mexico’s increasingly powerful criminal groups.

The victims — three women and six children — were members of the LeBaron family, part of a breakaway Mormon sect that has been based for decades in a remote stretch of Mexico not far from the U.S. border.

Eight other children survived the attack, spending hours hiding out in the Sonoran desert while one of them left to seek help. At least five of the children were wounded, authorities said, and were transported by helicopter to Arizona, where they are receiving medical treatment.

Relatives of the victims say the group — three women and their 14 children — had just left the community’s ranch near the small town of Bavispe in three vehicles when they were ambushed.

One of the vehicles caught fire, seemingly after a bullet hit the gas tank, killing a mother and her four children, family members said. The other victims were apparently shot to death.

The isolated desert region where the attack took place is a fiercely contested drug and migrant smuggling route about 100 miles south of the U.S. border. Authorities are largely absent, said Daniel LeBaron, a cousin of one of the victims, who said his relatives had been stopped at checkpoints set up by criminal groups in the past.

“They are living in a dangerous area,” LeBaron said in a phone interview Tuesday. “It’s ground zero of a turf war.”

Mexican Security Secretary Alfonso Durazo said Tuesday that the assailants may have mistaken the victims for members of a rival criminal group because they were traveling in large sport utility vehicles, which are favored by Mexican cartels. Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador pledged a full investigation into the attack, and said of the region where the attack occurred: “It’s been a very violent area for a long time.”

The massacre quickly took on a political dimension when Trump tweeted angrily about it Tuesday morning. “A wonderful family and friends from Utah got caught between two vicious drug cartels, who were shooting at each other, with the result being many great American people killed,” he wrote.

It was not clear if the president had received intelligence about the attack or was simply speculating about what had happened — as is often his habit.

Trump also said the U.S. was ready to assist “if Mexico needs or requests help in cleaning out these monsters.”

“This is the time for Mexico, with the help of the United States, to wage WAR on the drug cartels and wipe them off the face of the earth,” the president tweeted.

His response was a pointed jab at Lopez Obrador, who has repeatedly said he does not want conflict with criminal groups and that the militarized strategy of his predecessors turned Mexico into a “graveyard.”

Mexico and the U.S. have long cooperated on security under the Merida Initiative, a multibillion-dollar partnership under which the U.S. has trained Mexican police and soldiers and pushed for other criminal justice reforms.

In recent weeks, amid criticism from other U.S. officials that Mexico does not have a cogent security strategy to fight rising violence, Lopez Obrador has said the U.S. must respect Mexico’s sovereignty.

Mexico will act alone to fight organized crime, he said Tuesday morning at a news conference.

“We are very grateful to President Trump, or to any foreign government that wants to cooperate and help,” he said. “But in these cases we have to act independently, in accordance with our constitution and our tradition of independence and sovereignty.”

The massacre Monday is the latest in a string of violent incidents in Mexico that has created the biggest crisis yet for the young Lopez Obrador administration.

Last month, 13 people were killed in a botched federal operation to capture a leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel in the city of Culiacan. Mexican forces decided to release the leader, Ovidio Guzman, after the cartel laid siege to the city for several hours.

A few days before that, 14 state police forces were ambushed and killed in Michoacan state. In August, the bodies of 19 people were hung from a bridge or dumped nearby in another city in Michoacan. Also that month, 27 people burned to death when criminals firebombed a strip club in Veracruz, allegedly after its owners failed to produce extortion payments.

The desolate borderland where Monday’s massacre took place has long been one of the most lawless parts of Mexico, and has recently been disputed by two criminal organizations: a group linked to the Sinaloa cartel and another linked to the Juarez cartel.

The Mormon presence in the region dates to 1886, when the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began cracking down on polygamists, and a sect that embraced polygamy fled the U.S. and purchased 50,000 acres of land in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

In 1944, a member of that community, Dayer LeBaron, acting on what he said was a message from God, moved about 35 miles south and established his own homestead, known as Colonia LeBaron. The community based in Bavispe, Sonora, has close family ties to the residents of Colonia LeBaron.

The LeBaron sect, whose members have now mostly eschewed polygamy, has a turbulent history. In 1993, three people who were part of an offshoot of the group were convicted in Texas of killing three former members and an 8-year-old child.

In more recent years, the group has had conflicts with locals over natural resources — namely water rights — and has also been victim to organized crime.

In 2009, assailants captured and killed two members of the group, including Benjamin LeBaron, a great-grandson of its founder.

LeBaron, a U.S. citizen, had led anti-violence protests after his teenage brother was kidnapped and held for a $1-million ransom. The family refused to pay the ransom, and the teenager was eventually released.

Another LeBaron brother, Julian, became a well-known peace activist in subsequent years.

For many who were raised in the LeBaron communities in Mexico, the massacre was proof that a once-idyllic setting had turned treacherous.

Growing up in Bavispe, Leah Staddon spent long hours every summer riding horses and rumbling along riverbeds in ATVs. She longed for each Thanksgiving — a chance for everyone in the community to come together.

“There were never any problems when we were kids,” said Staddon, now 38.

She moved to Queen Creek, Ariz., when she was in her late teens, but would visit Bavispe nearly every year. She hasn’t been back since February 2018 because of the increasing presence of cartels, which have stopped family members along the roads.

“We have not felt safe,” she said.

By Tuesday afternoon, many of her Facebook friends had changed their profile pictures to black ribbons with the message “OREMOS POR LEBARON” — they were praying for the family.

Staddon spent Tuesday afternoon at Banner-University Medical Center in Tucson, awaiting news about some of the children who had been airlifted to the hospital.

She said her cousin, Christina Johnson, was killed in the attack and that her cousin’s baby was found alive in one of the vehicles.

Daniel LeBaron, whose cousin, Rhonita Maria Miller, died with her children, said he hopes the killings bring a new perspective to the issue of violence in Mexico.

“This is something that everyday Mexicans are living,” he said, adding that he believes that both Mexico and the U.S. bear responsibility.

“It’s time that we looked seriously at the policies of both governments, which are failing,” he said.

Linthicum reported from Mexico City. Lee reported from Phoenix. Cecilia Sanchez in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.