Young filmmakers train a fresh lens on turbulent Cambodia

- Share via

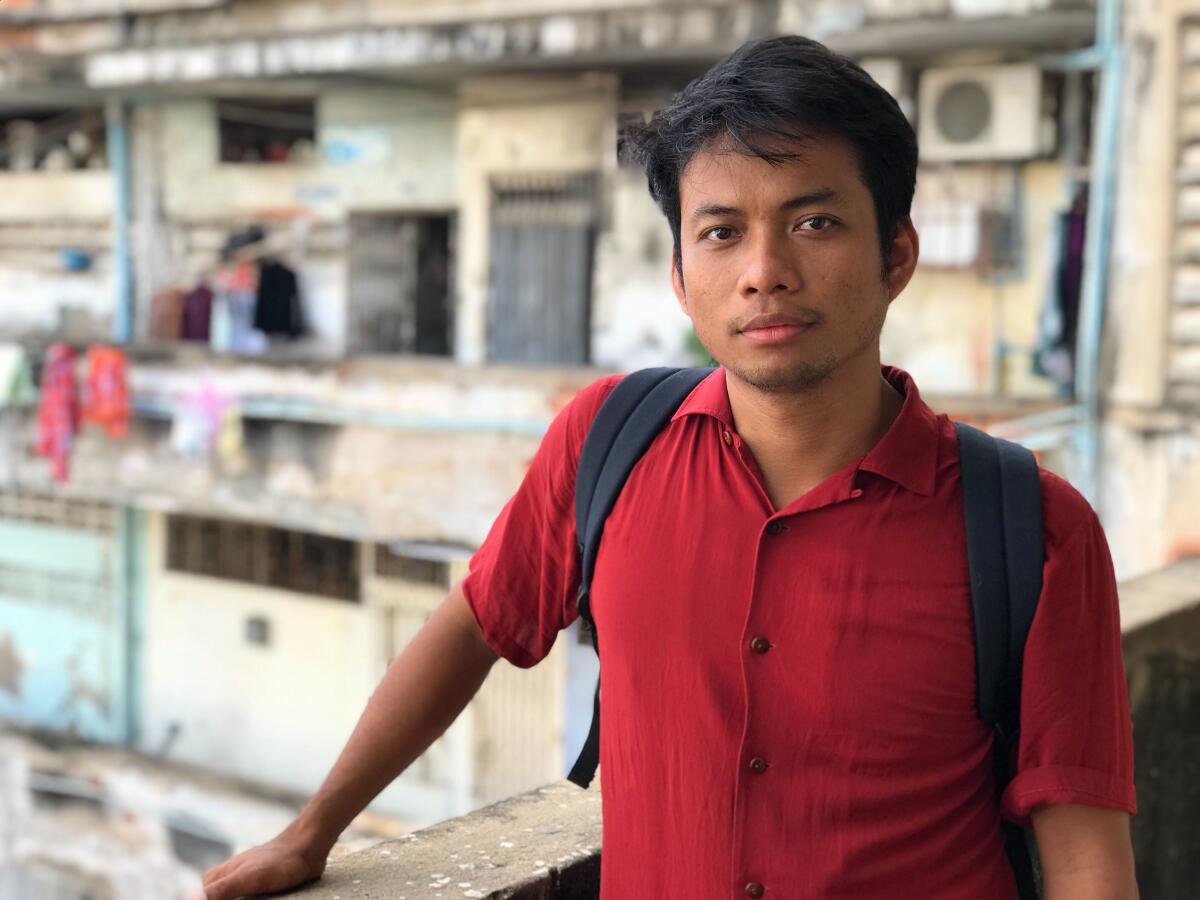

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia — When Kavich Neang learned that Cambodian authorities were going to knock down the storied apartment building where he’d been raised and replace it with luxury condos, the young filmmaker’s first thought was to grab a video camera.

“I just wanted to capture what my family and everyone else was feeling,” Neang said. “I had always thought I would shoot a fiction film there. But now I just wanted to have some memory of the place.”

With a borrowed camera, Neang shot for five weeks inside Phnom Penh’s decaying White Building as the wrecking ball loomed in 2017, recording his parents and neighbors as they packed their belongings, pleaded with officials for fair compensation and fretted about an uncertain future in the fast-changing Cambodian capital.

The footage would form Neang’s first feature-length documentary, “Last Night I Saw You Smiling,” which this year won awards at festivals from Rotterdam to Los Angeles. One critic called it “an important film about how to deal with concepts like origin and home in our world.”

It was the latest successful project by Anti-Archive, a small Cambodian production house that is reviving independent cinema in a country where artistic voices have often been sidelined by turbulent politics.

Anti-Archive has produced or co-produced nearly a dozen films since its launch in 2014 by Neang and two other directors, French Cambodian Davy Chou and Taiwanese American Steve Chen. A fourth partner, South Korean-born Park Sung-ho, joined in 2016.

Members of the collective work behind the scenes on one another’s films, and occasionally appear in front of the camera as well. Their films have won honors at festivals worldwide, helping to put Cambodian cinema back on the global map and boosting a new generation of filmmakers raised in the shadows of the horrors inflicted four decades ago by the genocidal forces of the Khmer Rouge.

The totalitarian communist movement blamed for the deaths of about 2 million Cambodians viewed most art and film as decadent, particularly anything seen to have foreign influences. When the Khmer Rouge took over Phnom Penh in 1975, the occupants of the White Building — a government housing complex adopted by artists — fled the city along with most other residents of the capital.

Over the next four years, many filmmakers, writers, painters and intellectuals were killed or went into exile. By the time the Khmer Rouge was driven from power in 1979, a once vibrant domestic film industry had vanished. Film prints had been destroyed or gone missing, and nearly all movie houses had been shut down.

Today, Cambodia has one of Asia’s fastest growing economies, flush with investment from China. But under the three-decade rule of Prime Minister Hun Sen, free speech, which saw a resurgence after the ouster of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge, has been sharply curtailed. The government has shut down independent newspapers and radio stations and recently jailed a Cambodian translator on a Russian sex-trafficking documentary that authorities dismissed as “fake news.”

Though Anti-Archive’s films are not overtly political — many revolve around ordinary people seeking to make a place amid the rapid redevelopment of contemporary Cambodia — they represent a radical departure from the supernatural horror films and broad comedies that dominate the country’s mainstream cinema.

Challenging those conventions is a way to make a statement, Neang said.

“We are all traumatized from the past,” said Neang, a slim 31-year-old with a shock of dark hair. “My parents always talk about it. Growing up, they always told me, ‘Don’t do this, don’t do that.’ It makes you distrustful. So as a society we don’t take chances.”

Neang’s father was a sculptor, and his mother had a brief career as a dancer. He had considered pursuing traditional music until he worked with a nonprofit group that was producing a short film, and soon he was hooked.

Neang was encouraged by Chou, the 35-year-old dean of the group, whose parents raised him in France after the Khmer Rouge came to power. Chou made his first visit to Cambodia a decade ago and found only two movie halls in Phnom Penh, each screening low-budget horror films.

“It was a desert,” he recalled.

Chou, whose grandfather had been a film producer in Cambodia before the Khmer Rouge ascended to power, had a production company in France and had already directed and produced several films when he came to Cambodia in 2014 to shoot his first feature, “Diamond Island,” about a young villager who travels to the capital to work on a construction site.

Chou wanted to cast nonprofessional actors and spent his days scouting the city for talent. In the evenings, he occasionally invited about a dozen friends and crew members to his house for drinks and a film by a contemporary Asian director.

“In this country it’s hard to have access to art house films on the big screen, so it was a way to open minds about other kinds of films, and it made me very happy,” Chou said.

One evening in 2015, he screened “Tropical Malady,” a dark, dreamlike romance by director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the first entry from Thailand to win a prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Danech San, then a 23-year-old budding interior designer, recalled being baffled and entranced.

“My first thought was, this is totally different from anything I’ve seen in theaters,” San recalled. “I didn’t understand it all, but the images stuck in my mind.”

The daughter of a soldier from rural Cambodia, San was used to conforming. She liked black coffee, but her mother thought it too masculine. She was interested in the arts, but her parents thought she’d never make a living.

“I wasn’t used to speaking my thoughts,” San said. “But we’d watch these films, and Davy would ask what do you think about a certain scene or a certain technique. He would push a little bit, step by step. It was a space with people who were really supportive.”

San worked as a production manager on two Anti-Archive films and took a filmmaking course, then began thinking about writing her own script. In 2017, Anti-Archive launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise money to finance three short films by first-time female directors — including San, now 27.

The goal was to raise $15,000 in 15 days. They ended up receiving more than $28,000.

Last year, San’s 20-minute film, “A Million Years,” about a woman’s reflections as she and a friend visit a riverfront restaurant, was selected for the prestigious film festival in Busan, South Korea, and won prizes at festivals in Singapore and Hamburg, Germany.

“It was beyond all of our expectations,” Chou said.

Without any financial support from the government, the collective has financed its projects largely through grants from international foundations that support the arts. The films remain better known outside the country: only “Diamond Island” was released in Cambodia, and it was pulled from theaters after less than two weeks.

“I didn’t have any famous actors, the story was not a comedy or a horror film, so it was hard to attract the mainstream audience,” Chou said.

This fall, Anti-Archive will take on its most ambitious project to date: a feature written and directed by Neang about the experiences of three friends living in the White Building. Chou has signed on to produce.

“The most amazing thing about this group is how it encourages people to express themselves while Cambodian society doesn’t encourage you to express,” Neang said. “And the other amazing thing is that we are all friends, and we get to make films together.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.