Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

PISMO BEACH, Calif. — Twenty minutes into an uphill trek in the 880-acre Pismo Preserve, my small group of hikers rounded a turn as the noise from Highway 101 dissipated.

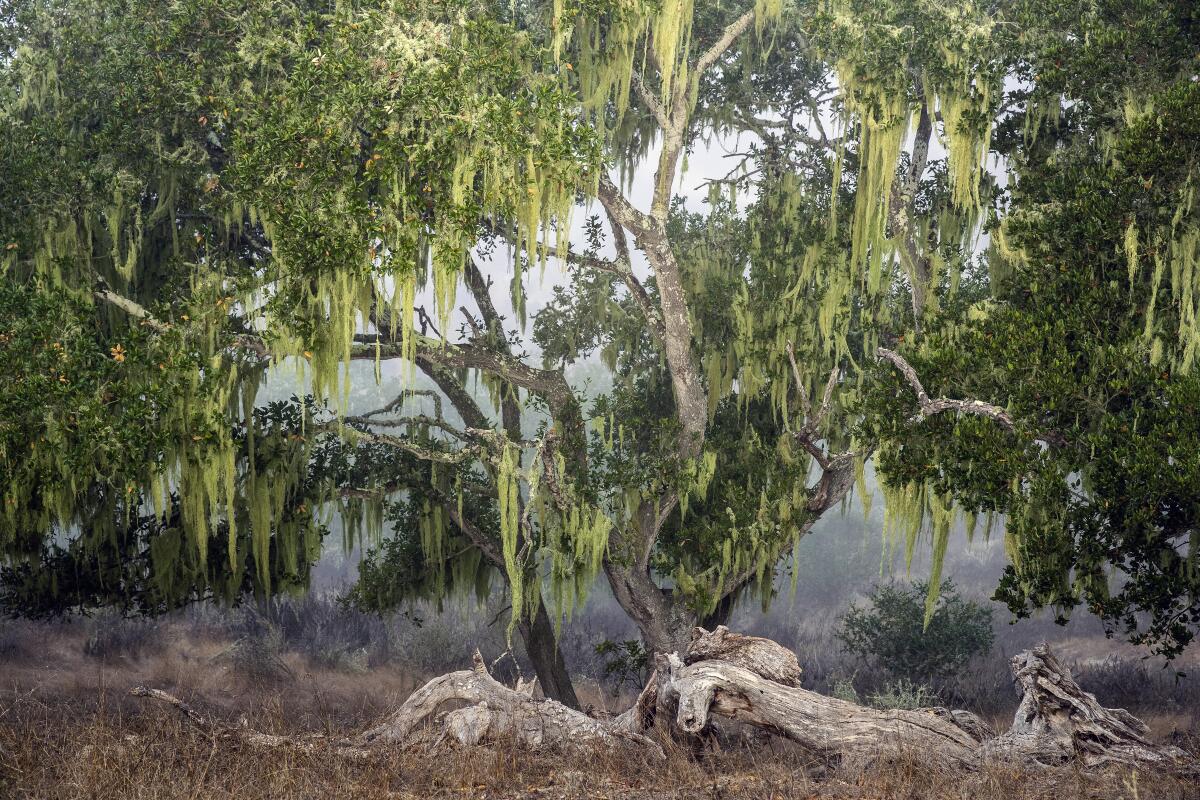

As if on cue, the preserve’s bonsai-like lone oak, which many consider its symbol, appeared through the fog and mist, growing out of a rock pedestal.

Other coastal live oaks stood nearby as if in deference. They were lovely in their own right, with weathered branches draped with long, pale-green lace lichen dotted with dew.

The preserve, which opened in January above Pismo Beach and is the latest addition to San Luis Obispo County’s recreational options, rises more than 900 feet above the Pacific with 360-degree views in some places.

The former ranch features nearly a dozen miles of trails, of all levels of difficulty, for hikers as well as equestrians, runners and mountain bikers. An Americans With Disabilities Act accessible path is planned; ultimately, the preserve will have 14 miles of trails when all the loops and connections are completed.

The oaks and dangling lichen, which I first mistook for Spanish moss, grabbed our attention on that misty October day.

And the deeper we got into the preserve, the more enchanting the oak forest, its canyons and rock outcrops became. In fact, if one of J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits had hopped out of a tree, I wouldn’t have been surprised.

Kaila Dettman, executive director of the Land Conservancy of San Luis Obispo County, the nonprofit that acquired the property in 2014 after raising $12.5 million, said naturalists flock to the preserve for its native flowers, other flora and the chance to see bobcats, badgers, black bears, foxes, deer and an occasional mountain lion.

On a hike she led for a group of potential donors, Dettman recalled seeing a red-tailed hawk land less than 20 yards away as a humpback whale breached in the ocean below.

“And, no, I didn’t plan on that happening,” she quipped. “But some of the people on the hike thought I might have arranged it.”

Dettman said that once the coastal fog clears, broad vistas offer views of the Pacific from the Irish Hills Natural Reserve in the north to Point Sal State Beach in the south. That panorama, which includes the 1,200-foot-long Pismo Beach Pier, makes the hike to the preserve’s highest ridgelines on the Panhandle Trail or Peekaboo Loop worthwhile, she added.

A longer outing on the Discovery Loop can take about four hours, while my trek on the Spring to Spring Trail tallied 2½ hours at a moderate pace.

Dettman, a self-described “native-grass nerd,” said one of her favorite plants in the preserve is purple needlegrass, which can live as long as 100 years and once covered hillsides on the Central Coast.

She’s also fond of the endangered black-flowered figwort, the showy, deep-blue phacelia and the pink hummingbird sage.

For flower enthusiasts, she recommends hiking in March through May; oaks begin to leaf out in May and June.

She’s a big fan of the oaks too, of course: “It’s remarkable that those tough old oaks have survived on the ridgetops above the ocean for hundreds of years,” she said.

On our stroll, Dettman said the former ranch has been home to the native Chumash people who have lived along the Central California coast for 10,000 years. She said the conservancy has worked closely with members of the tribe, who consider the land and its burial grounds sacred.

“This tribal history is yet another reason why keeping the preserve in open space for future generations is important,” Dettman said.

The preserve also protects springs that dot the hillsides, providing birds, animals and insects a valuable source of water year-round. “We’re protecting the water quality of Pismo Creek too,” she added.

The former ranch also serves as a corridor so wildlife can reach the ocean, she said. Though the Land Conservancy doesn’t own property on the west side of Highway 101, Dettman said, critters move at night using the freeway underpasses, culverts, stream crossings and bridges to reach the Pacific.

“At Avila Beach Drive, for example, there is a wide underpass they likely use after traveling through the preserve and onto neighboring properties that would lead them to the San Luis Obispo Creek Corridor and into the Irish Hills,” she said.

Dettman said the preserve owes its existence, in part, to the Great Recession of 2008-09.

Josephine Peak is easy to find and close to home. Plus, register for a virtual group walk the length of California, and learn why campgrounds have closed in the state.

The land was slated for commercial and luxury home development, but the economic fallout from the recession nixed those plans. The ranch’s corporate owners then contacted the Land Conservancy to see if it was interested in the property, and a deal was struck.

As the economy began to rebound, Dettman said the owners in early 2014 gave the conservancy 10 months to raise the funds or forfeit the option to buy the land, which still has limited cattle grazing.

“We set off at a whirlwind pace to let people know we needed the money fast, but word spread and it just took off,” Dettman said, noting that the conservancy also received state and local grants.

“The actual purchase price was $11.5 million, but we needed another $1 million to support the project. We couldn’t have done it without the tremendous local and regional support.”

Mary Sampson, a transplanted Oregonian who is a Land Conservancy docent along with her husband, Rob DeGraff, said she cheers up every time she visits the preserve, which she sometimes does several times a week. They live in San Luis Obispo, a 15-minute drive.

“We moved here 11 years ago and almost immediately began volunteering with the conservancy,” she said. “Since the land was acquired for the preserve, we’ve become cheerleaders and hike leaders. We really consider it our baby.

“Now, especially during the pandemic, it’s great that people are able to have another open space to get out and enjoy nature.”

Sampson said when a wildfire approached Pismo Beach this fall, firefighters told television news reporters one of their major concerns was saving the preserve.

The L.A. Zoo, campgrounds and playgrounds closed are again.

“That was really heartening to hear that as the fires were raging, they weren’t talking about million-dollar homes on the edge of the fire, but the trees and the wildlife of the preserve. It truly is becoming an important part of the community, sort of its heart and soul.”

If you go

Pismo Preserve; check the website to make sure it’s open. Entrance and parking lot are on the east side of Highway 101 (Exit 191B) at the southern end of Mattie Road. Open dawn to dusk daily, including holidays. Free. Dogs on leash OK.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.