5 lifesaving tips for when you spot a bear on the trail

- Share via

I was drifting to sleep in my tent, soothed by the crisp night air, when I heard one word that jarred me back to reality.

“Bear!”

You are reading The Wild newsletter

Sign up to get expert tips on the best of Southern California's beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains in your inbox every Thursday

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It was just after 10 p.m. at the Sentinel Campground in Kings Canyon National Park, and I was alone in my tent. I shined my flashlight around my campsite and confirmed that I had no unexpected visitors. I listened as campers farther away shouted “Bear!” as it moved past their campsites, the sound echoing around like we were all playing a forest version of Marco Polo where the bear was “it.”

It was unsettling to not know exactly where our visitor was. But soon enough, the campers closest to the bear shooed it away. I lay back down, assuming the excitement was over for the night. Just as I was falling back asleep, I heard it again: “Bear!”

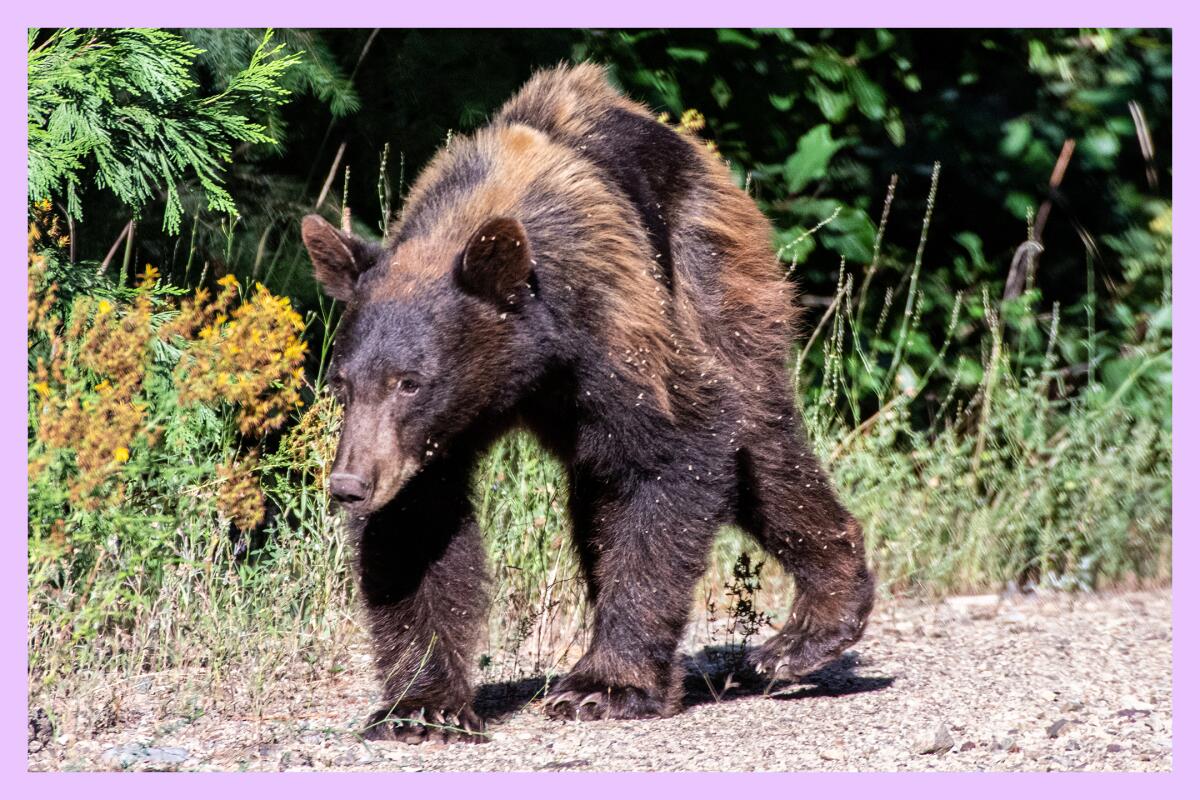

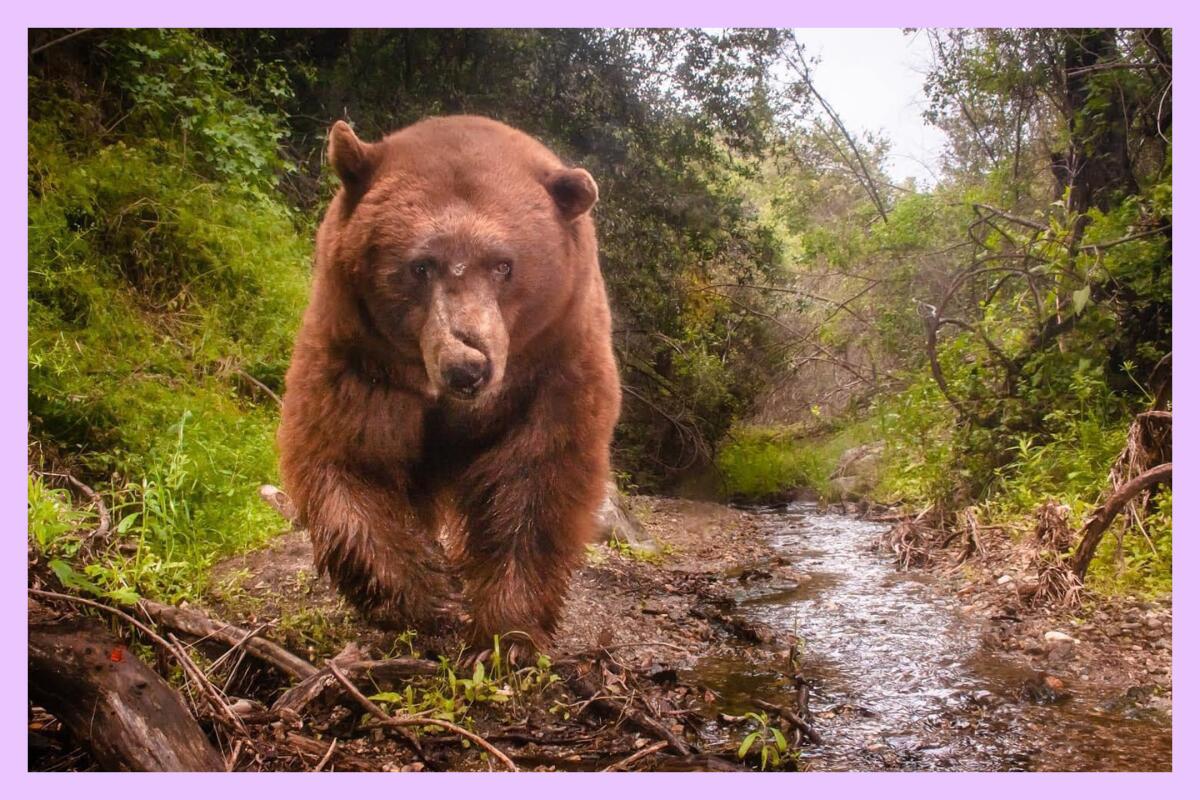

This one — a small brown bear — decided to come my way, walking about 20 feet from my tent before hopping onto a log, walking its length and then wandering off to another corner of the campground.

That was both the closest I’ve ever been to a bear outside of the zoo and the only time I’ve seen a bear in the wild outside of a car. It underscored two things for me: just how thin my tent’s walls were and that I needed to learn more about how to react should a bear come my way.

An estimated 65,405 black bears live in California, with the majority in Northern California and the Sierra Nevadas, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Southern California has a relatively small portion of those bears — an estimated 3,167 (depending on which regions you include in your count). Despite that, one of the biggest hot spots in the state for human and black bear conflict, according to wildlife officials, is in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. That “conflict” is mainly reports of property damage, loss of livestock and other unwelcome behavior.

Not only that, but we have the possibility to see them year-round because bears in the L.A. area generally don’t hibernate.

“There’s just no reason to,” said Jake Owens, director of conservation at the Los Angeles Zoo. “During the wintertime, there’s still food, and it doesn’t get so cold that they need to really conserve energy by hibernating.”

Despite all those factors, dangerous bear encounters are rare.

“The amazing thing about Los Angeles is that we have all this wildlife in and around our neighborhoods and so infrequently does anything happen,” Owens said. “That says ... the relative threat is really low. The more you can do to reduce it even further and help us coexist is just a benefit.”

That’s the goal of today’s Wild. I’ve put together some tips so that if you ever see a bear while hiking, you’ll know what to do. They’re also helpful if you run into a bear in your neighborhood or, like me, your campsite.

A quick note: Although some of it might still be relevant, this guidance is about how you respond if you see a black bear, not a grizzly bear. If visiting an area with grizzly bears, be sure to talk with rangers and other local experts who can provide guidance for best practices in that area.

1. Don’t run

How you react to a bear depends on several factors, including the distance you are from the bear, how it’s acting and how it reacts to you.

But the one thing you absolutely must not do is run. You will look like prey. Every expert I spoke with emphasized this.

Also, don’t climb a tree. Bears can climb trees quite well. Stay on the ground.

2. Let bears know you’re there

As lovely as the serenity of the woods is, it’s important to make some noise while you’re hiking, whether that’s talking in a low voice or noisy footsteps, to let bears and other wildlife know you’re there.

I often hike alone with my dog, Maggie May, and because of that, I will frequently let out a loud “Hey-ooo,” to let everyone know I’m around. (Occasionally, a nearby hiker will answer back.) Owens, with the L.A. Zoo, told me that making noise like this is important because it lets any bears around know there’s a human nearby.

The same goes for when you actually see a bear.

If you see one far in the distance that’s headed away from you, it’s still important to let the bear know you’re there. Say something loudly and calmly — don’t shriek! — like “Hey, bear!” in a deep voice. Bears have a keen sense of hearing, and it likely will hear you and run far away. (Bears also have great noses, so if the wind is right, it might also smell you from a quarter mile away.)

“If it’s headed toward you, again, make sure you know that it knows you’re there,” Owens said. “Talk loudly in as deep a voice as you can get. Put your hands up and out — don’t shake them around — but make yourself look big, and try to get the bear’s attention without indicating that you’re scared or that you’re a threat to that bear.”

Owens suggested making a motion with your arms similar to that of making a snow angel, slowly waving and being big. You can also open up your jacket if you’re wearing one to appear even bigger.

“You’re not trying to shock it, and you’re not trying to make it seem like you’re scared and that it can come and chase you away,” Owens said. “You’re just trying to say, ‘Hey, I’m here. Know that I’m here. Please get off the trail.’”

Additionally, if you have a child with you, you should either pick your child up, or if too large to pick up, put that child directly behind you. And you want to make sure your child knows to stay calm and not scream.

“Talk to the child loud enough for the bear to hear, and tell them, ‘It’s a bear, and we’re sharing the trail,” Owens said. “Keep on facing it so you’re not turning your back to it.”

If you have a dog, the dog might scare the bear away before you have to take any action, Owens said. However, if your dog is barking and growling, and that’s upsetting the bear, it’s good to either pick up your dog or pull it close and stop it from barking.

3. Keep your eye on the bear

Now that you’ve made yourself big and the bear knows you’re there, it’s important to keep your eye on the bear.

But don’t look it in the eye. That can be seen as you threatening the animal or that “you think you are more dominant or that you’re going to come after them, so they can become more afraid, and they can become territorial, especially if it’s a male,” Owens said.

4. Observe its behavior and react accordingly

OK, so now you’re being big, you’re talking to the bear and keeping your eye on it.

Take a moment to understand why the bear is coming toward you. Does it have cubs? Is there a cub behind you? Is the bear scared or trying to scare you? When a bear is walking toward you, oftentimes, Owens said, it’s because there’s something in that direction it wants.

When bears feel threatened and want to scare you, they will chomp their teeth and huff, Owens said. The most frightening thing they’ll do is bluff-charge, where they’ll run at you, and then some distance away, they will stomp on the ground and huff loudly.

If a bear bluff-charges you, you need to leave immediately. “That’s the bear saying, ‘You’re too close, you need to get away from me, you’re scaring me, I feel threatened,’” Owens said.

You should start slowly backing away, Owens said, telling the bear, “OK, I’m leaving.”

If the bear is just standing on the trail looking at you, then you should also start backing away. The bear still wants space but hasn’t indicated it yet, Owens said. As you back away, keep talking to the bear, telling it you’re leaving.

“Bears are extremely smart animals, and so it can tell from your voice, it can tell from tones” how you’re feeling, Owens said.

Oftentimes, in the Santa Monica and San Gabriel mountains, the trail has a steep cliff on one side and a shear drop-off on the other, meaning neither you nor the bear can easily move off trail.

In that instance, “Just keep on backing up,” Owens said. “Keep your eye on the bear. As you go around a corner, maybe speed up a little bit until you can see the bear again, and you might have to go back a ways until the bear can find an easy place where it can go down or up as well. But just keep on talking to it and keep your eye on it. But you do not want to run away. You do not want to go toward the bear at all.”

5. Carry bear spray

The National Park Service advises: “Only use your bear spray when the bear is charging or attacking you.”

That said, if it’s a windy day, or if the wind is blowing toward you, you could end up with a face and lungs full of bear spray. Make sure you know how to deploy it long before you ever need to use it.

That covers what you should do on the trail. When camping, you should always store your food in a bear box. Owens adds an additional layer of protection: he places all his food and toiletries in a thick black trash bag within the bear box to cut down on any odors. This helps deter bears from coming to the campground in the first place.

That said, not all campgrounds in Angeles National Forest have bear boxes. In that case, officials advise storing your food in your car and covering it. Luckily Angeles National Forest hasn’t had incidents of bears breaking into cars, like some national parks have. And although still not ideal, it’s better than leaving all your food out and around your campground, where bears could easily reach it and develop bad habits.

Remember, it’s rare to see a bear in Angeles National Forest.

“If you see a wild bear in a wild place doing wild things, consider yourself incredibly lucky,” said Dana Dierkes, public affairs officer at Angeles National Forest.

Let’s do our part to keep them wild.

3 things to do

1. Collect data on a Spanish-language evening hike in Agoura Hills

Join rangers for a Spanish-language hike from 5:30 to 7 p.m. Sunday to collect data at the Paramount Ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains. Participants should meet at the Biodiversity Booth at the dirt parking lot before heading out. It’s one of many free events during Hispanic Access Foundation’s Latino Conservation Week, which aims to increase access and involvement of Latinos in the outdoors. You can learn about hikes, biking, yoga, talks and other activities on the lineup by visiting the week’s list of events. To register for the Spanish-language hike, visit eventbrite.com.

2. Explore the ocean’s microscopic diversity in Huntington Beach

Sure, sharks, whales and dolphins are great, but have you ever wanted to know about the tiny things teeming around in the tide? You can help monitor phytoplankton at Bolsa Chica State Beach through a community science effort from 9:30 to 11:30 a.m. Friday. You’ll collect an ocean water sample and use on-site equipment to observe the microscopic organisms living in it. The event is part of the Amigos de Bolsa Chica’s FLOW, a community-based water quality research program aiming to better address pollution in the region. No previous experience is necessary, and training is ongoing. Learn more at amigosdebolsachica.charityproud.org.

3. Let the kiddos get their hands dirty in Pasadena

Have some cooped-up kids? Head over to Patagonia Pasadena, 47 N. Fair Oaks Ave., for “Kids Day: Planting and Crafting.” Children will learn about button making and have other crafting opportunities; they can also learn about a local farmers market. Capri Kasai, from Arlington Garden in Pasadena, will teach children about breeding or reproducing of plants. Bonus: Kids will have the opportunity to take home their own plant friend. No registration is required. For more information, visit the event page.

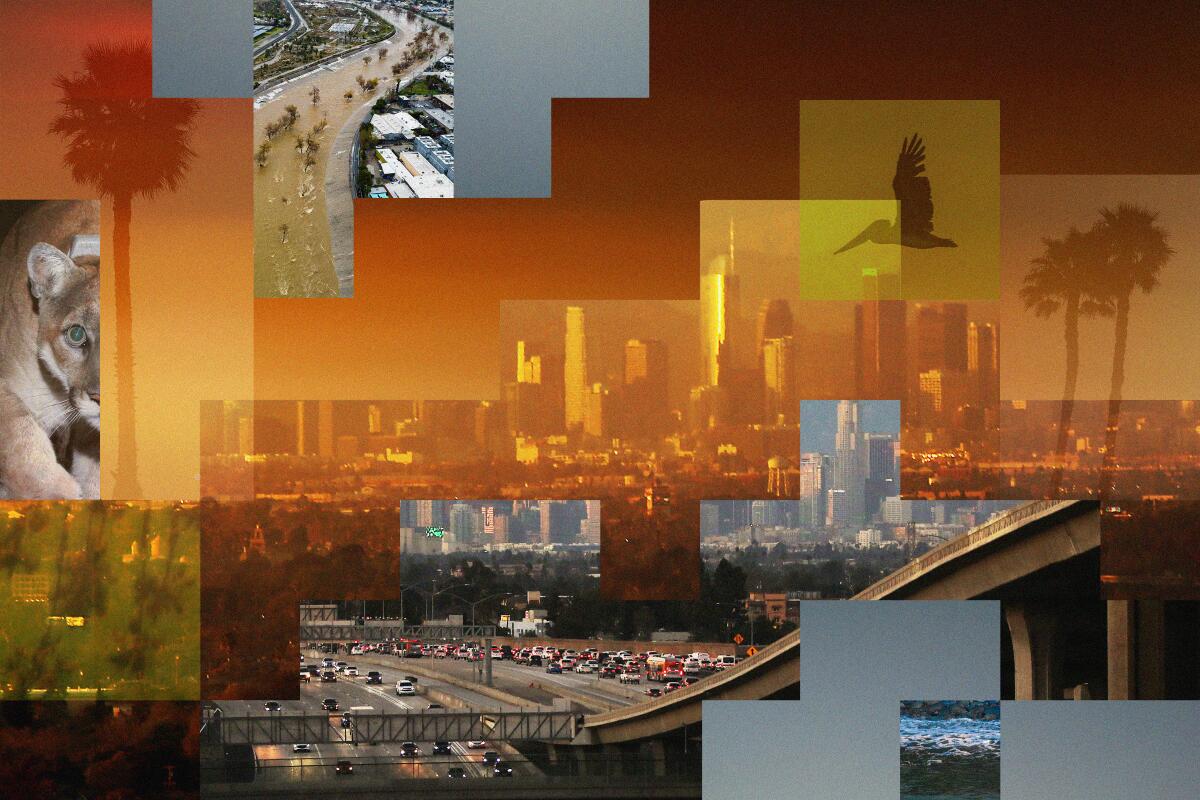

The must-read

It’s easy to descend into a doom spiral over climate change. But one of the most important messages you’ll find in The Times’ special project, Our Climate Challenge, is from Kristina Dahl, a principal climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists: Keep trying. That’s not to say that our lives in L.A. won’t change. In her contribution to the package, Times environment reporter Hayley Smith outlines how climate change will alter our lives in L.A. We’ll drive less, sweat more and say goodbye to our lush, green lawns. We’ll also probably phase out our iconic palm trees, replacing them with native trees that provide actual shade. “We need to count tree canopy and its maintenance as an infrastructure investment,” said Marta Segura, L.A.’s chief heat officer. “We should no longer look at it as something that’s nice to have, and not even as just the lungs of the city. It actually reduces the temperature and the urban heat island like no other solution.”

Our Climate Challenge publishes in print Sunday. You can find a copy where papers are sold, buy one online or read the content on our site.

I know it’s hard, but I do have hope — in you, me and young activists like those included in this project — that we can band together and save our planet from the worst of this.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

I have something to add to your list of cool seasonal animal behaviors in California. Samuel P. Taylor State Park, about an hour northwest of San Francisco, is one of the only state parks with an active salmon run. From about October through December, you can watch the fish cross Lagunitas Creek, which runs through the park.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.