10 beloved L.A. trees that Angelenos should enjoy — and protect at all costs

- Share via

There are easily hundreds of truly excellent, some might even say great trees in Los Angeles. Are these 10 the very best? Well, that’s totally subjective. For our story “The greatest trees of Los Angeles,” photographer Devin Yalkin and I transited Los Angeles many times, looking for trees, keeping in mind that the trees we were after, the trees we thought were great, had to be as public as possible. That is, you don’t have to pay to see any of these trees, and they are often beside city streets. All also, in one way or another, tell us a story of our city and what the land was like even before the city was here. They tie us back to its history, its people. These trees have been here a long time. Most of them have been here longer than any of us. We could learn a thing or two from them. So get out there and visit, and go find 10 more of your own.

I talked to arborists, landscape architects, gardeners, historians, activists, tree-heads and more, all to find an answer to my question: Which L.A. trees are the best trees, the ones worth celebrating?

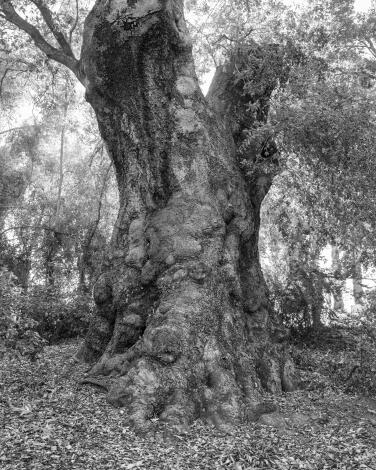

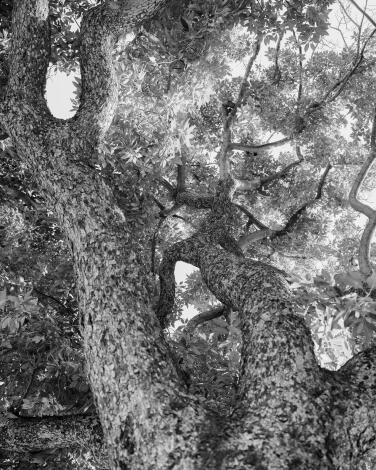

Coastal live oak (Quercus agrifolia), Orcutt Ranch

The coastal live oak in the back of Orcutt Ranch, in West Hills, is, however, still very much alive, and quite possibly the oldest tree in Los Angeles — a truly awe-inspiring specimen, well worth spending an hour or two beneath while attempting to count the countless number of birds that will come and visit this massive tree, delighting in its hugeness as you do the very same.

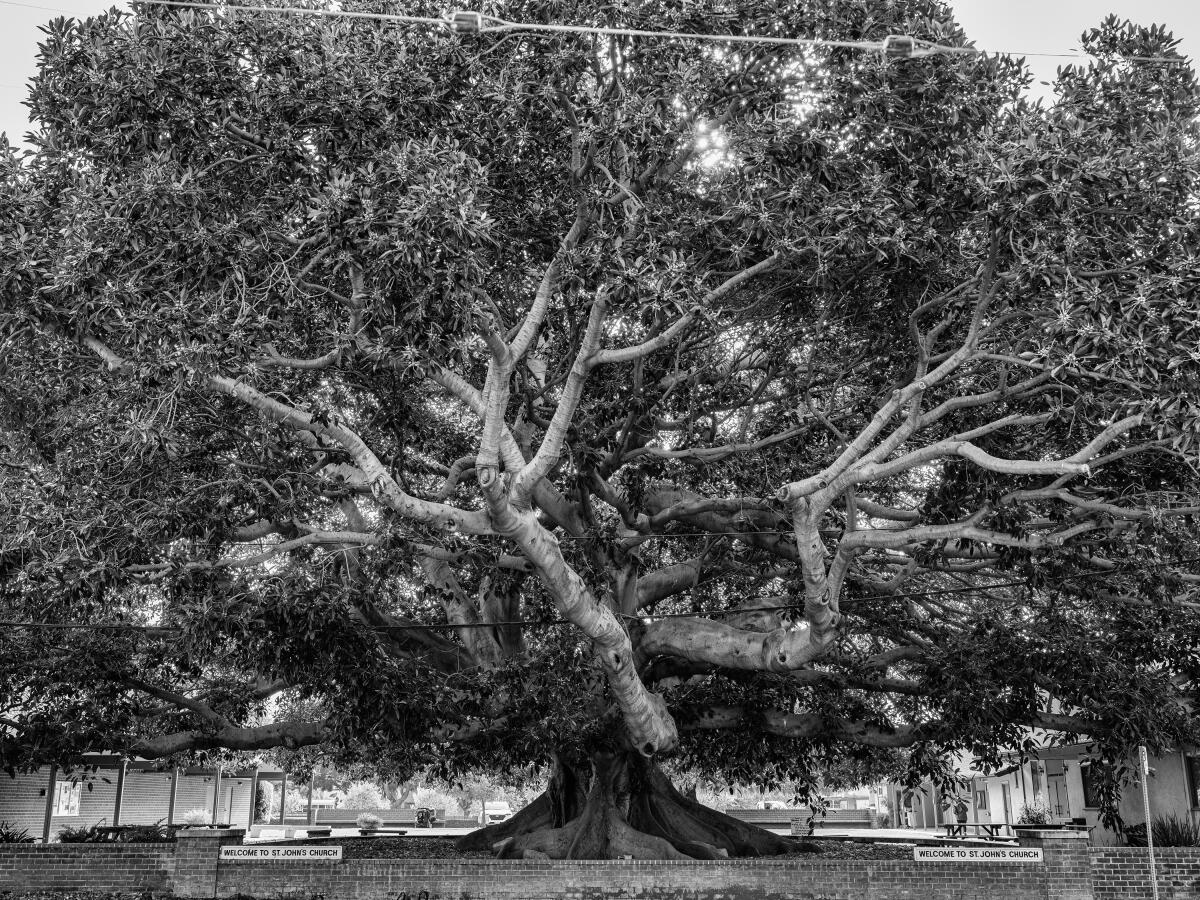

Moreton bay fig (Ficus macrophylla), St. John’s Presbyterian Church

This tree, next to St. Johns, was planted well before the St. John’s Presbyterian Church was there, in honor of the original property owner’s firstborn son. It lays claim to being the second largest in California. Then again, the big tree in Big Tree Park, in Glendora, claims to be either the first or second biggest in the state, too. So does the Moreton fig up in Santa Barbara, by the train station. Though, the back cover of Donald R. Hodel’s “Exceptional Trees of Los Angeles” states that the Glendora tree is “the most massive cultivated tree in the greater Los Angeles area” and “the patriarch of them all.” Here is what we all can agree: Moreton Bay figs are very big and very amazing. We are so lucky to have so many.

Floss silk tree (Ceiba speciosa), Yamaguchi Bonsai Nursery

'El Pino' bunya-bunya (Araucaria bidwillii)

Mexican avocado (Persea americana), Atwater

But this avocado, on a quiet street in Atwater Village, near the L.A. River, is both a national champion and the kind of tree that is central to L.A. history, for in the 1890s, Juan Murrieta began importing great quantities of the fruit from Atlixco, Mexico. One variety Murrieta named after himself, others he named Sharpless and Colorado and Challenge and Dickey. None of these are grown commercially anymore, but they paved the way for huge commercial groves close to the river, in both Atwater and Los Feliz (around Avocado Street, naturally) where plenty of these more- than-a-century-old avocados can still be found today.

Jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia), Cahuenga, Franklin and Wilcox triangle

But people, the arborist told me, obviously care more for trees than they do for billboard advertisements. When we visited, a man named Louis Alfaro approached. He was very worried about what we might be doing to the tree — did we work for the city? Was Devin photographing the site to take down the tree? It was one of the few patches of nice green shade, and there was already so much vandalism around it, Alfaro said. He’d lived in an apartment in the neighborhood for 11 years, and visited the tree almost every day.

Rose gum (Angophora costata), the end of Chevy Chase Drive by the L.A. River

Grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi), Isamu Noguchi Plaza, Japanese American Cultural & Community Center

Hirokazu Kosaka, the master artist in residence at the JACCC, has been the tree’s caretaker for about 40 years. “I know the tree very well,” he says. He was there for its transplanting. “You know, after the Japanese Americans were interned, most of the men became gardeners here in Southern California. In the 1950s and ‘60s, there were 28,000 Japanese American gardeners here. They recognized the importance of this tree, and they moved it. It was in good shape then, abundant with fruit.”

Kosaka recalls delivering more than 100 grapefruits to retired people in the community the first few seasons it was in the plaza. “But now, you know, the tree is dying.” He bandaged it, to help prevent its dry bark from getting more sunburned during the last drought. This winter it has had no blooms and no fruit. The tree has a sister, on First Street North, and that one is still producing, but remains under threat by possible development.

Camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora), Evergreen Cemetery

Western (or California) sycamore, Platanus racemosa

The trees were markers of significant locations, Teutimez said: villages, mostly. And later: burial grounds. “The fact that it’s a hardwood, too, means sycamores provide us with a whole other slew of gifts: They were utilized in the funeral pyre, they were the wood that sends you on to the next part of existence, so part of them becomes part of you.” Also for music. “Many folks have a misunderstanding that every Native American group had drums, but we didn’t have drums in Southern California, because we didn’t have the animal skins for drums,” Teutimez continued. “But what we did have was sycamore. And what you can do with sycamore is an instrument made out of two sycamore bowls. You make two bowls out of the wood of two different diameters. The big bowl, you fill with water, and the smaller bowl goes down into water, making a little round dome. You get a soft mallet, and bang on it, and the reverbrance out into the water is like a bass drum, a guttural, whomp whooomp whooomp.”

The tree’s uses go even beyond all this: “It can even take care of you in the spring,” said Teutimez. “Its new leaves are some of the most soft velvety and strong material you could ask for, if you’re ever out of toilet paper.”

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.