A trip on Route 66 proves to be uncharted territory for a master planner

- Share via

The plan was to have no plan. To head east on Route 66, a solo traveler with no agenda. Stopping when I felt like it. Staying as long as I wanted. Moving on when I was ready.

There was only one problem: I’m a master planner. Traveling with me has always been the vacation equivalent of a military assault.

I promised myself that this time would be different. No to-do lists. No reservations. I wanted to search for a connection to the places and the people along the fabled Mother Road.

As I set out on my nine-day journey in October, I kept my expectations low and my hopes for adventure high, with a goal of enjoying the journey and living in the moment.

Your ultimate guide to planning the best summer road trip »

Los Angeles to Needles

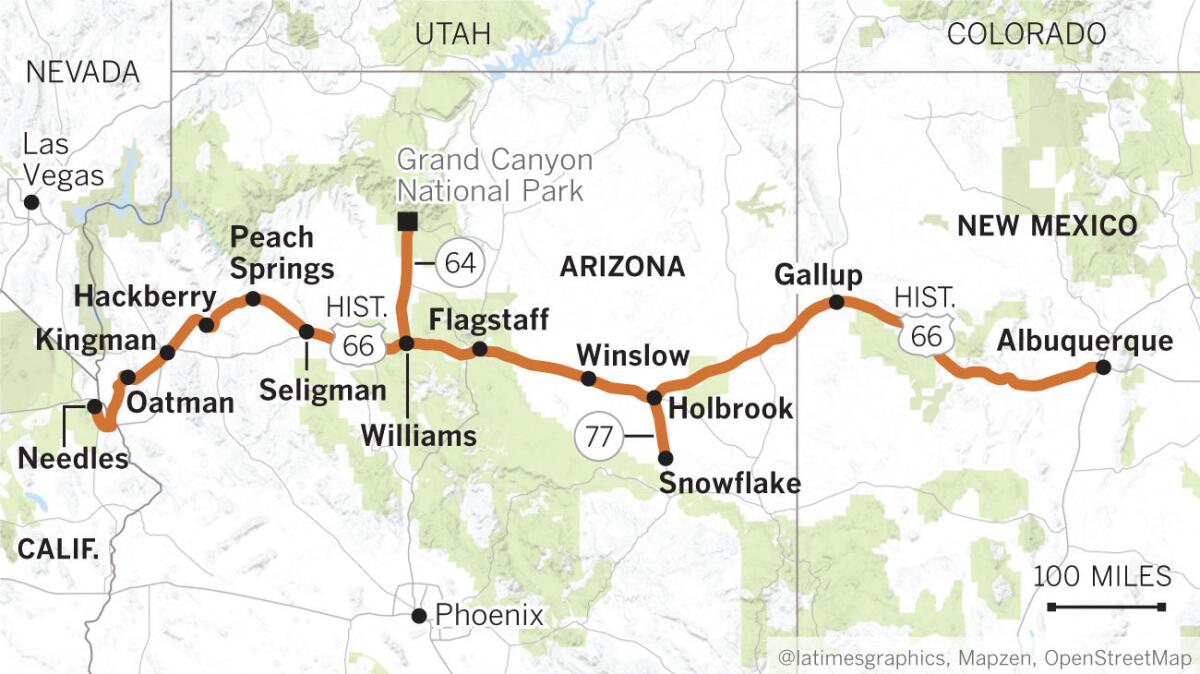

Route 66 was established in 1926; the plan was to stitch together a series of regional roadways into a national highway system, that, when completed, ran from Chicago to Santa Monica.

Its decline began in the mid-1950s with the birth of the interstate highway system, and the death knell came in 1985 when Route 66 was officially decertified. But a revival began soon afterward, driven by enthusiasts who did not want to let that era disappear from the American narrative.

Over the years I’d stumbled upon stretches of Route 66 in Pasadena, San Bernardino and Victorville, but I figured I could always explore the California segment another time. My goal on this trip was to get to Arizona and New Mexico — and maybe even the Texas panhandle.

I left Los Angeles early on a Saturday, heading northeast to Barstow, where I merged onto Interstate 40, the transcontinental highway that has largely supplanted Route 66 in the Southwest. I didn’t stop until I got to Needles, my exit marked by a sign that I’d see often during the next several days: Historic Route 66.

Stopping for gas, I discovered the station store was filled with souvenirs emblazoned with the iconic black-and-white Route 66 crowned road sign. Outside, a park bench offered a place to enjoy the panoramic view of the Black Mountains — and my first destination.

When I asked for directions, mechanic Rick East pointed northeast to a ring of craggy peaks about 20 miles away, cloaked in a light haze. "See that hump? That’s Oatman,” said East. “It’s crazy; 66 used to run up there.”

It still does.

Oatman, Ariz.

In 1915 Oatman changed — virtually overnight — from a small mining camp to boomtown after prospectors discovered a new source of gold worth millions. Eventually, Route 66 brought more visitors who streamed through the town until a bypass was built in 1953.

Today, the main drag of Oatman, about the length of three football fields, has become something that resembles Disneyland’s Frontierland. Covered wooden walkways flank both sides of Main Street, where nearly every shop caters to the tourists who come for a faux taste of the Old West.

The highlight of any visit to Oatman on the weekends is the mock Wild West shootout. The cowboys, part of a volunteer group that serves as a de facto tourism bureau, mill around town, mixing with visitors and posing for photos before the loud, action-packed showdown.

After the gun smoke cleared, I moseyed into Oatman Hotel Restaurant & Saloon ([928] 768-4408) for a buffalo burger and a chance to inspect $150,000 in dollar bills that cover the walls and part of the ceiling. The practice started when miners would hand the bartender a dollar and drink until they were out of money. The bartender would stick the money on the wall and scrawl the patron’s name across the bill.

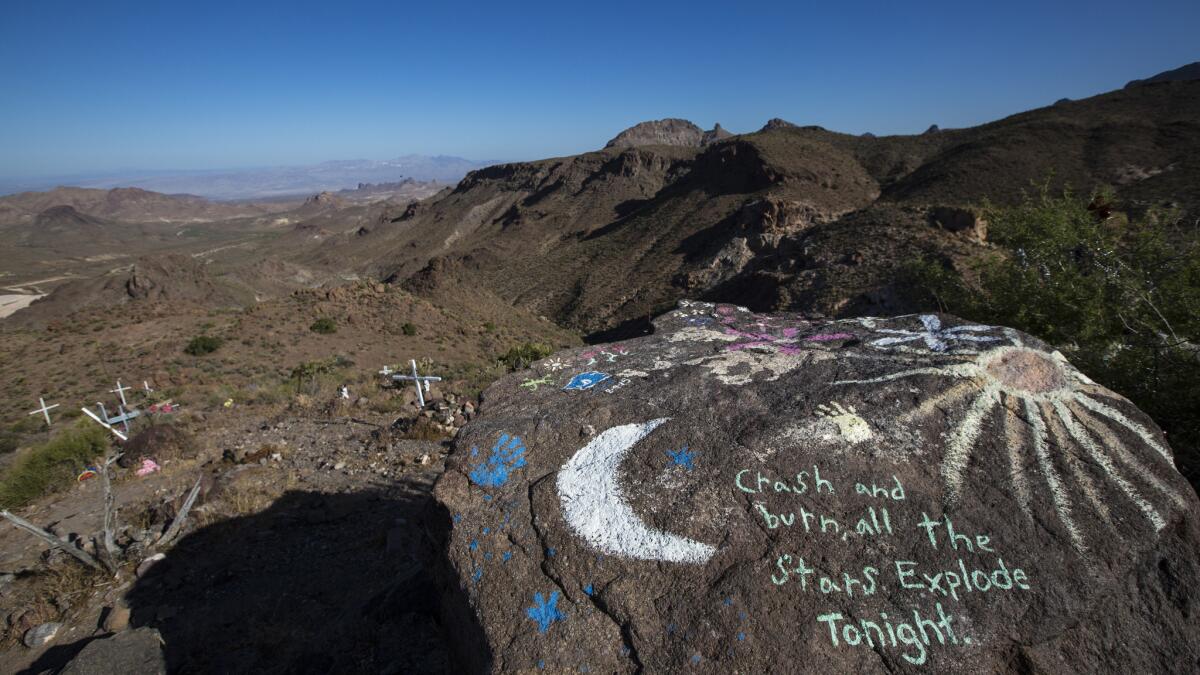

When it came time to head east to Kingman, Ariz., I had to confront my fears about the Oatman-Topock Highway — an old Route 66 alignment — which looked like a squiggly series of spaghetti switchbacks that might spell an early end to my journey.

The narrow two-lane road left little room for error, with hairpin curves and drop-offs of several hundred feet at several spots. I strongly considered a roundabout route to Kingman by way of I-40, but a parking lot attendant in Oatman told me I’d be fine if I stuck to the speed limit, which is 10-15 mph in many spots.

After a few white-knuckle miles, I pulled off at an overlook populated by 65 motorcycles. The rocky point offered a spectacular view of the rugged mountainside, a few shadows dappling the jagged desert-scape from the clouds above.

READ MORE | Oatman offers a taste of the wild west with wandering burros and mock shootouts »

Kingman, Ariz.

I spent the first night of my trip in Kingman at El Trovatore Motel ([928] 753-6520, doubles from $76 a night), established in 1939 during Route 66’s heyday. I stayed in the “Clint Eastwood” room — a theme that amounted to a pair of movie posters on the adobe walls and a plaque on the door. The slightly dated furnishings looked as though they’d been picked up at a Las Vegas hotel clearance sale, but the tiled bathroom looked original — from the tiny corner sink to the preschool-height toilet.

The El Trovatore offered everything I was looking for in a Route 66 motel: a little roadside history mixed with a bit of chintz and kitsch.

I ate breakfast at the Rutherford’s 66 Family Diner ([928] 377-1660), where the beautifully browned, flaky biscuits satisfied another of my goals: simple meals in roadside restaurants that maintained the spirit and mystique of Route 66.

Kingman to Seligman, Ariz.

One of the longest unbroken segments of Route 66 stretches from Kingman to Seligman, a flat black ribbon that rambled between endless fields of green scrub ringed by distant purple mountains.

On my way out of town, I had to stop at the Hackberry General Store ([928] 769-2605), which looks like a movie set surrounded by roadside artifacts, vintage gasoline pumps and rusting Model Ts. The souvenir shop served as an inspiration for the Radiator Springs Curio Shop in the 2006 “Cars” movie, an animated film that sparked my interest in Route 66 and the real-world inspirations for the fictional Radiator Springs town.

The next stop was Grand Canyon Caverns ( [928] 422-3223), in Peach Springs, where a 200-foot-deep elevator shaft takes visitors down to a labyrinth of limestone passageways filled with stalagmites and stalactites.

When I got to Seligman, I experienced the biggest highlight of the road trip: a haircut from a 90-year-old barber named Angel Delgadillo, a storyteller with a comedian’s timing. His Original Route 66 Gift Shop ([928] 422-3352), a major stop for any Route 66 pilgrimage, includes a small barber shop in the front corner of the store.

As Delgadillo will tell you, in a nearly nonstop monologue interrupted only by the constant stream of tourists snapping his photo, he helped establish the Historic Route 66 Assn. of Arizona in 1987, and his family is mentioned in the “America on the Move” permanent exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“This town is really the America of yesterday,” Delgadillo said.

Read More: Haircuts, hamburgers and history await on Route 66 in Seligman, Arizona »

Grand Canyon

I raced out of Seligman in hopes of making it to the Grand Canyon National Park, just north of Route 66, in time to catch the sunset — but missed it by five minutes. I caught a spectacular twilight, however, and vowed to wake early the next morning for sunrise.

Then I had to find a hotel room, knowing that my “no plans” strategy would be put to the test. I tried all the hotels inside the national park looking for a last-minute cancellation. The answer was the same everywhere: rooms were sold out for months.

I did, however, find a room at my fallback hotel, the Red Feather Lodge ([928] 638-2414,, doubles from $152 a night), about a mile from the South Rim entrance.

Because I couldn’t stay at the majestic El Tovar Hotel ([928] 638-2631) in the park, I figured I’d eat a pre-sunrise breakfast there the next morning in preparation for my hike into the canyon. The steep descent on the Bright Angel Trail concerned me, knowing every step into the canyon would be twice as difficult on the way out.

All the huffing and puffing hikers heading up the trail had the same look on their face. I wondered if I might turn back before I had anticipated.

But the farther I descended, the more my perspective of the canyon changed. The intermittent sunlight and shadows brought out a breathtaking array of colors in the layers of rock.

After about an hour, I reversed course and began my ascent. And I followed the advice of the guy in front of me: I took it slow.

READ MORE | Majestic sunrise makes up for missed sunset at awe-inspiring Grand Canyon »

Holbrook and Snowflake, Ariz.

As I drove east, I called the Wigwam Motel in Holbrook, Ariz., about two dozen times trying to book a room for the night, getting no answer and leaving countless messages. (Turns out the motel office didn’t open until 3 p.m.)

When I stopped by the tepee-rimmed motor court, I was told they had no rooms but I was welcome to add my name to the waiting list — behind 15 others. It was my first big disappointment of the trip, but my spirits were buoyed by the Rainbow Rock Shop a half-mile away. A towering herd of colorful plaster dinosaurs — the work of a welder named Adam Luna — stood guard over the small store, which is surrounded by piles of petrified rocks.

After striking out at the Wigwam, I settled on the Heritage Inn Bed and Breakfast ([866] 486-5947, rooms from $105 a night) in Snowflake, Ariz., a town founded in 1878 by Mormon pioneers Erastus Snow and William Jordan Flake.

But I booked my room with the innkeeper without realizing just how far the B&B was from Holbrook (about 25 miles). The undulating two-lane road was surrounded by endless expanses of pitch-black nothingness, and the experience taught me a valuable lesson: Arrive at unfamiliar places before nightfall.

Albuquerque, N.M.

It took only one phone call to find a room at my next stop, Albuquerque. The House of Peace & Love ([505] 797-3228, rooms from $95 per night) turned out to be a cross between a hippie commune, artist’s studio and B&B in a suburban tract that the innkeeper described as the “Beverly Hills of Albuquerque.”

The next morning I wandered around the heart of historic Albuquerque along Central Avenue (a.k.a. Route 66). At Lindy's Diner ([505] 242-2582) I had the cowboy breakfast with chicken fried steak covered in green chile. Around the corner, I found a pair of Navajo hair ties for my daughter’s braids at Skip Maisel’s Indian jewelry shop ([505] 242-6526).

Then I slipped into the 1927 KiMo Theater ([505] 768-3522), a structure rich with Southwest architectural details, during a volunteer orientation session before I took a two-day detour and drove to Taos and Santa Fe.

Gallup, N.M.

Starting my drive home on the sixth day, I picked up Route 66 west of Albuquerque and headed for Gallup, where I spent the night at El Rancho Hotel ([505] 863-9311; doubles in the historic building start at about $108), billed as the “Home of the Movie Stars.” The impressive two-story lobby was filled with signed photos of Hollywood celebrities.

The next morning I had breakfast — huevos rancheros with eggs over easy, red chile and sopaipilla with honey — at the Eagle Cafe, ([505] 863-2233) in operation since 1889.

Down the street, I walked into Richardson's Trading Co. ([505] 722-4762), where a sign on the door read “Buying Pinons.” Sue Richardson was kind enough to explain that pinons are pine nuts and let me taste some of them. The store buys the nuts in bulk and resells them.

“They're addictive,” she said.

Holbrook and Winslow, Ariz.

Driving west, I was thinking about giving the Wigwam Motel (rates from $69 a night) in Holbrook another shot, and I lucked out — there was a cancellation. The following morning I had breakfast — a wonderful polenta and egg dish — at La Posada Hotel, ([928] 289-4366) in nearby Winslow, Ariz., where I later spotted people standing in the middle of an intersection — 2nd Street and Kinsley Avenue — snapping photographs of a green space.

I realized that I couldn’t leave without visiting the Standin’ on the Corner Park , named in appreciation of the Eagles’ “Take It Easy.”

There’s even a flatbed Ford permanently parked in just the right spot for a photo op.

READ MORE | Persistence pays off with a last-minute cancellation at Holbrook's Wigwam Motel »

The way home

I drove to Flagstaff, Ariz., then to Williams, Ariz., and then my Route 66 road trip was unceremoniously over. I spent the night in Laughlin, Nev., and sped back home the next day. I’d traveled 2,225 miles on my trip and learned a few valuable lessons.

There will always be a hotel somewhere along the road. Meeting people makes the journey more enjoyable. You’ll see more if you slow down. And it really is possible to travel without a plan.

ALSO

Hang loose in the circle (or maybe it's the square) of Old Towne Orange

Besalú, the most interesting Spanish village you've never heard of

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.