At San Diego Zoo, stare down giraffes, breakfast with pandas

The venerable San Diego Zoo invites long and repeated visits. There are, after all, more than 3,700 animals to get to know. Plus, the Australian Outback area was just updated.

- Share via

You and I both know where to find an endless supply of watchable animals — felines, canines, reptiles, eating, sleeping, swinging, swatting, spooning. It's hard to look away. Time flies by.

"Yes," you say with a sigh. "The Internet is ruining us."

Probably. But I'm talking about the San Diego Zoo, an actual physical place that might not be a waste of time.

FOR THE RECORD:

San Diego Zoo: Articles in the Oct. 27 and Dec. 29 Travel sections about the San Diego Zoo reported that its $99 Backstage Pass program included the cost of zoo admission. The cost of admission ($46 for adults) is separate. More ticket information can be found at zoo.sandiegozoo.org/tickets. —

Here, without benefit of mouse, monitor or smartphone, you can lock gazes with a viper, smell elephant scat and coo at an adorable giant panda — until you hear the menacing crunch of that 230-pound bear's sturdy teeth, snapping and shredding an inch-thick bamboo stalk.

That was Bai Yun, a 22-year-old mother of six, tearing into breakfast while I watched and winced one morning last month.

Even though most of its residents are captive non-natives, the zoo is an iconic Southern California creation all the same, with more than 3,700 animals from 650 species, surrounded by 700,00 plant species and ogled by 3.5 million visitors last year.

If it weren't for that pesky St. Louis Zoo (3,519,926 visitors last year), San Diego's would be the most-visited facility of its kind in North America. The zoo's leaders might prefer to emphasize its role in helping bring back pandas, California condors and other threatened species, but in simple gawk-and-snap terms, this territory has been a 100-acre photo op since before Kodachrome was born. In the 1930s, the zoo veterinarian used to roam the grounds between chores with a Graflex camera, then sell the prints at the front gate. (That vet, Charles Schroeder, went on to run the place from the 1950s into the 1970s.)

San Diego is my default zoo. Just as my daughter counts on seeing Reggie the alligator on her way into the L.A. Zoo (1,100 animals; about 1.5 million visitors yearly), I grew up with the Skyfari buckets dangling above and pink flamingos squabbling at the entrance. In the Children's Zoo, I rode the Galápagos tortoises, and a goat once peed on me.

There were no goats on this trip, but in the several days that L.A. Times photographer Mark Boster and I spent roaming the grounds, there was plenty of sensory stimulation: One afternoon, passing the California condors, I glimpsed a tuft of unexpected fur on the rocks — a fresh spread of dead rabbits and rats, laid out by the keepers, for the scavengers' brunch. At the Backstage Pass program, I got slimed by rhino spittle, howled in harmony with an arctic wolf whose fur was as white as snow and fed flamingos using one of those red plastic cups you used to misplace at frat parties.

I highly recommend the flamingo feeding. You sit on a bench with cup in hand, and the long-necked, sharp-beaked birds come at you like a squadron of pink Concordes. As they snap up the snack pellets, you feel their beaks rattling in your cup.

The next morning in the Conrad Prebys Australian Outback area — a major updating of the zoo's Australian collections that opened in May — we looked on while keeper Kate Tooker gave the female koalas their eucalyptus fixes, then paused to cuddle a wallaby. In the next enclosure, keeper Lindsay King whispered sweet nothings to a male koala while it paced a few feet on a branch, climbed a few steps up a trunk, then settled in to munch leaves.

For a koala, which sleeps about 16 hours of every 24, this was whirlwind activity. And in this new setup, they're easier to see — closer to visitors, less cloaked by foliage.

Of course, most zoo visitors will also want to pay visits to the lions, tigers, elephants and giraffes, and so did we. (One of the giraffes stared me down for so long I thought it might demand to see my ID.) But I set aside more time for my old friends the tortoises, which have been part of the zoo since arriving from the Galápagos in 1928.

This looked like a mistake at first: Beyond the boulders upfront, I saw no sign of life in their enclosure. Then a boulder budged and a scaly, dark-eyed, primordial face emerged. Then another.

At the San Diego Zoo, two Galapagos tortoises square off in a contest for dominance. These giants are the zoo's oldest residents.( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

While I looked over those faces, keeper Jonny Carlson brought me up to date. In 1972, keepers stopped letting kids climb aboard. Nine of the zoo's original tortoises are still here, plus one that arrived in the '30s. They bask in the sun to warm their cold blood, snap up greens from their keepers and — as I witnessed — occasionally bloody each other's noses in lumbering battles for dominance. In other words, they're no better than Congress.

And as in Congress, their tenure is closely tracked — in this case by the numbers painted on their shells. That's how we know No. 5, nicknamed "Speed," which weighs close to 600 pounds. He arrived in 1933. He was estimated to be in his 60s then, so he's near 140 now, the oldest animal in the zoo.

There's a good chance that Speed's mother and father were lumbering around on one of the Galápagos islands in 1835 when a man with a notebook showed up and started tapping on tortoise shells. The man even sat on a few, finding it "very difficult to keep my balance." Then he went home to England with his notebooks and wrote "The Origin of Species."

That's right: By the tortoise calendar, you and I are just one generation removed from Charles Darwin.

San Diego Zoo: Its history and some fun facts

The zoo's birth. Pandas give birth. A connection to the start of YouTube. This is a fertile place.

1916: Inspired by a lion's roar and worried about what would become of the exotic animals in the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park, surgeon Harry M. Wegeforth founds the San Diego Zoological Society.

1923: Grand opening in Balboa Park. Adult admission is 10 cents.

1925: First koalas, kangaroos, emus, wombats and dingoes arrive from Australia. Belle J. Benchley, a former teacher, is hired as a temporary bookkeeper.

1927: Executive secretary Belle Benchley ascends to the role of zoo director. For many years, she is the only female zoo director in the world. She serves until 1953.

1928: First Galápagos tortoises arrive.

1931: First gorillas arrive from Africa: Mbongo and N'gagi, later to be celebrated by bronze busts near the entrance.

A present-day photograph of the flamingo pond contrasted with a postcard from the 1960s. (Photograph: Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times.)

1930s: Caught in a Depression-era tax dispute with county officials, the zoo's property and animals are put up for auction but attract no bidders. Zoo veterinarian Charles Schroeder stretches the budget by feeding carnivores horse meat from Mexico.

1941: In Orson Welles' "Citizen Kane," the San Diego Zoo stands in for the Xanadu menagerie of Charles Foster Kane.

1953: Benchley retires and is succeeded by former zoo veterinarian Charles Schroeder, a forceful advocate for moats instead of cages.

1964: SeaWorld, a for-profit venture founded by four UCLA grads who originally wanted to build an underwater restaurant, opens on San Diego's Mission Bay. It's an immediate success, kicking off long-standing competition with the zoo.

1969: The zoo unveils the Skyfari, an overhead gondola that gives visitors a bird's-eye view of the park and travels about 1,800 feet. Annual attendance reaches 3 million. Zoo management decides to hire a photogenic young woman as Miss Zoofari, a goodwill ambassador who makes public appearances with animals.

1970: Joan Embery, a 21-year-old Children's Zoo attendant and San Diego State student, is chosen as the second Miss Zoofari.

1971: Joan Embery, joined by Carol the painting elephant, appears Nov. 4 as a guest of Johnny Carson on "The Tonight Show." It goes well. During the next 38 years, through the Carson and Leno eras, Embery is invited back more than 40 times. On one visit, a marmoset relieves itself on Carson's head. On another, a two-headed king snake crawls up the host's sleeve.

1972: The Zoological Society opens the Wild Animal Park, a 1,800-acre sibling of the zoo, in the hills of northern San Diego County. It's now known as the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

1975: The Zoological Society opens the Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species. Its efforts include the Frozen Zoo, a collection of frozen cell cultures that has grown to include more than 9,000 individual birds, reptiles, amphibians, mammals and fish.

1987: Fifteen years after the first arrival of Chinese giant pandas at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., the San Diego Zoo receives pandas Basi and Yuan Yuan on short-term loan from China.

1996: Giant pandas Bai Yun (female) and Shi Shi (male) arrive from China on long-term loan. Breeding efforts begin. (Shi Shi returns to China in 2003.)

1999: With the aid of artificial insemination, Bai Yun gives birth to cub Hua Mei.

2005: The first YouTube video, "Me at the Zoo," is shot in San Diego Zoo's elephant area and uploaded by YouTube co-creator Jawed Karim.

2010: Zoological Society trustees agree to a major name shuffle. Henceforward, the society will call itself San Diego Zoo Global. The Wild Animal Park will be known as the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. The Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species will be known as the Institute for Conservation Research.

2012: On July 29, Bai Yun gives birth to her sixth cub, Xiao Li Wu. Combined zoo and Safari Park attendance reaches 5 million. SeaWorld attendance: 4.4 million.

Sources: "Mister Zoo: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Charles Schroeder," by Douglas G. Myers with Lynda Rutledge Stephenson; Assn. of Zoos and Aquariums; https://www.sandiegozoo.org; library.sandiegozoo.org/history.htm; https://www.prsasdic.org/content.asp?itemid=92; https://www.aecom.com/themeindex

San Diego's thoroughly modern, gleaming new Central Library

San Diego's new $185-million library opened Sept. 30 and is a huge hit. There is a Seussian kids' area, baseball memorabilia, a fun gift shop and a roof-top terrace. And books.

San Diego's long-awaited, $185-million, nine-story Central Library opened for business Sept. 30. Architect Rob Wellington Quigley said the dome was in part inspired by the dome of the California Building, which has been a marquee building in Balboa Park since the 1915 Panama-California Exposition. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Will the peacock shrieks do it? The camel slobber? The aggrieved cries of other people's children? One way or another, you'll know when you've had enough of the San Diego Zoo..

That will be your cue to exit the zoo parking lot, turn right onto Park Boulevard, continue two miles and behold the gleaming new San Diego Central Library (330 Park Blvd.; [619] 236-5800, https://www.lat.ms/1fJMPwB). Goodbye, nature. Hello, literature.

The library is one long block from Petco Park, where the Padres play. From outside, it looks like a bullet aimed at the moon. From inside, everything seems to revolve around a thoroughly modern mission arch that soars three stories above the ground floor. The $185-million building, which opened Sept. 30, is more than twice the size of the city's old main library, which went up in the 1950s and was beloved by … well, nobody I could find.

There's plenty of excitement about the new one, though. Library spokeswoman Marion Hubband said the building drew 6,000 visitors to a Sept. 28 preview and an additional 7,500 on its first day of operations.

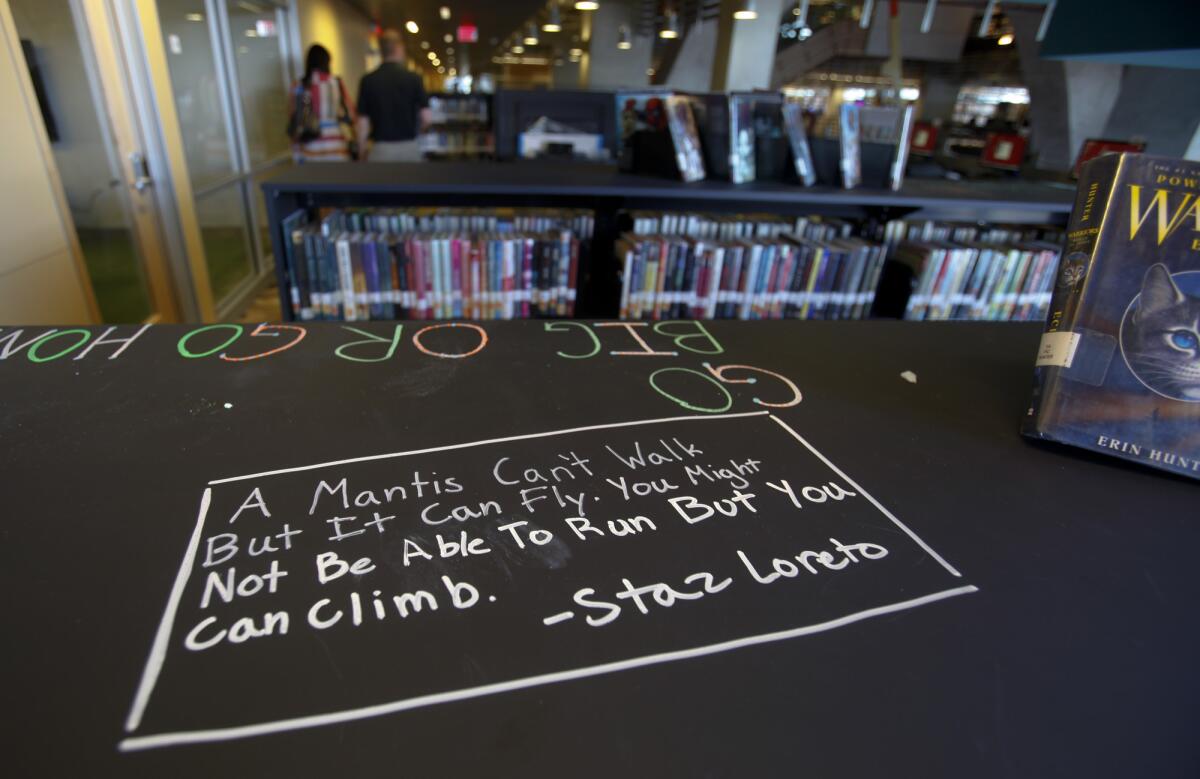

Besides bean-bag chairs and a snack area, the library's teen center features bookshelves faced with chalkboard material, awaiting chalked contributions. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Besides the building's many books, discs and electronic assets, parents will get a kick out of the manual typewriter ($75) for sale in the wittily curated gift shop. Kids will like the murals of Dr. Seuss characters in the ground-floor children's area.

Adolescent guests will be glad to see the teen-only area — with big bean-bag chairs and a snack zone — on the second floor. (Two floors of the building are devoted to a new high school, not open to visitors.)

Old and young will appreciate the sun-splashed eighth-floor reading room, with a big collection of baseball materials and memorabilia nearby. And then there's the terrace on top, where you can hear the wind rush through the metalwork that forms the building's dome.

That dome reaches 255 feet above street level. It was designed by San Diego architect Rob Wellington Quigley and Tucker Sadler & Associates to recall the dome of the California Building, which has been a fixture in Balboa Park since 1915.

Inside and outside, the library's walls are etched with literary quotations from Oscar Wilde, Toni Morrison, Jorge Luis Borges and others. This one is from novelist William Nicholson: "We read to know we are not alone."

The building has 250 parking spaces with 250 more across the street, and it stands within a few blocks of three trolley lines and 18 bus lines. So far, the small cafe in the library courtyard remains closed, but a spokeswoman said it would be open by the end of the year.

San Diego Zoo's panda keepers are Master Chefs of bamboo

When pandas aren't sleeping, they're eating a lot of bamboo. Staffers are on hand to feed and to explain.

The venerable San Diego Zoo is a top destination in the nation's eighth-largest city. And one of the top destinations within the zoo? The giant pandas, of course. The recently built Panda Trek houses four pandas that spend part of their day eating bamboo and playing, the other part sleeping. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

It takes a village to keep the San Diego Zoo's four giant pandas well fed and well understood. Two of those villagers are Jennifer Chapman and narrator Nick Orrantia.

Chapman, 38, has been a keeper for about three years, working with pandas, big cats and other animals. On panda days, she often starts at 6 a.m., pre-cracks the bamboo with a log splitter, cleans the living areas and releases the animals to eat, all before the first visitors arrive. (Tip: Panda lunch usually arrives at 11:30 a.m. or so, and dinner around 2:30 p.m. Watching them eat is more fun than watching them sleep.)

Orrantia, at age 24 a seven-year zoo veteran, is a narrator, which means studying binders full of scientific data and taking visitor questions. (The most common: Are giant pandas part of the bear family? Yes, he tells people, but scientists have only agreed on that since the early 1980s.) Sometimes Orrantia helps with keeper duties too.

Both Chapman and Orrantia spend much of their time focused on the animals' intake and output. So even if you interview the two separately, you get answers that weave together snugly. And you hear things you never imagined about bamboo and panda poop. For instance:

How much bamboo does an adult panda eat in a day?

"We offer 50-60 pounds," Chapman said. Of that, Orrantia said, they usually eat about 35 to 50 pounds.

Zookeeper Doug Kresl uses his friendly personality and a few snacks to charm the San Diego Zoo's greater one-horned rhinoceros, Surat. Visitors who buy a Backstage Pass excursion can get close to Surat, pose for photos and touch his rough skin. An inhabitant of the Urban Jungle area, Surat is also watchable from visitor pathways. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) More photos

They just eat bamboo all day, every day?

No. Over the course of a year, the pandas are offered about 45 species of bamboo, Chapman said. The keepers like to mix at least three species per feeding, Orrantia said, because in the wild the variety of bamboo species is often even greater. The bears also get occasional carrots, sweet potatoes, apples and biscuits. Their favorite treat: apples and honey water, Chapman said.

Do they all eat about the same?

No. Chapman said that Gao Gao, the male geriatric among the bears (an estimated 23 years old), has worn teeth and needs smaller, thinner bits of bamboo. Xiao Liwu, a cub born in July 2012, is still working his way up to an adult diet. Xiao Liwu's 22-year-old mother, Bai Yun, is far hardier and likes to chomp thick stalks, Chapman said. Her favorite bamboo, Orrantia said, is known as Buddha's Belly because its joints swell (like Buddha's belly) when it rains a lot. That apparently changes the flavor. Bai Yun likes it wetter.

So there's lot of bamboo going in. How does it come out?

A healthy panda poop, said Chapman, "is about the size of an avocado." The more leaves in the panda's diet, the greener the color, she said. If the panda has been eating only bamboo, Orrantia said, the poop "smells like a rotting pumpkin. Like the end of Halloween." The more non-bamboo items in the meal, the more intense the smell, Chapman said.

So after all these years eating bamboo, their digestive systems must be good at making use of it, right?

Wrong. The bears make use of about 17% of the bamboo they eat, Orrantia said, "and the rest goes right through." When pandas defecate, he said, "it looks like a piece of bamboo went through a wood-chipper."

What's the best part of a keeper's day?

It's usually early in the morning, Chapman said, when she faces the pandas through a fence, greets them and tries to elicit a series of "enrichment" behaviors before releasing them into the more spacious exhibit area. It lasts only about two minutes, Chapman said, but "it's my opportunity to interact — in a protective setting, of course — with the bears, and watch them look for the food I've put out for them." To keep the bears alert, keepers hide food items in different places daily. Keepers don't enter the exhibit area when a panda is present, "unless it's a cub up a tree, and then we have a second person watching the cub."

More Postcards From the West

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.