Postcards From the West: The West of old, new and myth meet in Durango, Colo.

Durango is home to the historic narrow-gauge Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, which offers breathtaking trips to nearby Silverton.

- Share via

Reporting from Durango, Colo. — Without railroads and mines, what would the American West be? Less populous, less prosperous, less polluted. And the town of Durango might not be anything at all.

Durango, sporty and historic, stands 6,520 feet above sea level among the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado, its downtown streets skirted by the Animas River. Look past the runners, rock climbers, kayakers and fly-fishers, past the rampant Subaru wagons, the snowboarders of winter and the second-home-owners of summer, and you’ll notice the narrow-gauge rail tracks alongside the river, leading into the mountains.

This is the route that brought the town to life in the 1880s. Built by the Denver & Rio Grande Railway in an 11-month blitz of blasting and trestle construction, this track for decades carried gold and silver from the mines outside Silverton (45 miles upriver), following a path that clings to cliffs and squeezes through narrow canyons.

Then, after mining began to fade in the late 20th century, the train began its second life, carrying Hollywood film crews and tourists. Nowadays, it carries hundreds of tourists daily — including L.A. Times photographer Mark Boster and me in late May — and no ore at all.

The last major Silverton mine closed in 1991, and the old Durango smelter and mill, which processed uranium from the 1940s through the ‘60s, have also shut down. Durango (population: about 17,000) has evolved into the sort of town that fuels city people’s semi-rural daydreams.

In the grand old Strater Hotel (built in 1887), just above the Diamond Belle Saloon, you can rent Room 222, where author Louis L’Amour spent many an August in the 1960s and ‘70s, writing his western novels and listening to the ragtime piano player downstairs. (But I’d rather sleep in Room 327— lots of exposed bricks and woodwork.)

On the seven-mile Animas River Trail (no motors allowed), the supply of runners and cyclists seems endless, many of them students at Durango’s Fort Lewis College.

At Mountain Bike Specialists on Main Avenue and 9th Street, you can pick up that SRAM 11-speed rear derailleur you’ve been pining for. Elsewhere along Main, if a storefront doesn’t house a brew pub, field-to-fork restaurant or art gallery, it’s probably a real estate office.

In fact, if you’ve been to Wyoming, you might say Durango is getting Jackson Hole-ier by the day.

As in Jackson, someone, or some plaque, is bound to remind you of the many saloons, whorehouses, feuds and shootouts the city once sustained. One day in 1906, for instance, the county sheriff and the Durango town marshal shot each other in a dispute over who should control local gambling. (The sheriff died. The marshal, Jesse Stansel, moved to Texas.)

And one day in 1922, after an argument involving Prohibition, the Durango Democrat’s top editor, Rod Day, shot to death the Durango Herald’s city editor, William L. Wood.

The big conflicts on the Herald’s front page during my visit were a little different. In one, Durango and Anchorage were competing to be named the “Best Town in America” by readers of Outside magazine (only to be eliminated by Provo, Utah, and Duluth, Minn.).

In another, hundreds of cyclists were preparing for the 43rd Iron Horse Bicycle Classic, a Memorial Day ritual in which cyclists race the train to Silverton, only to have a snowstorm shorten the route. In a normal year, mountain bike salesman Jeremy Thompson told me, “The fast riders always beat the train. The fastest guys do the race in about 2 hours and 20 minutes.”

The train? Its standard one-way journey to Silverton takes 3 1/2 glorious hours.

Whether or not you recognize the trackside scenery from the dramatic 19th century photographs of William Henry Jackson or old movies such as “Around the World in 80 Days” (1956), odds are good you’ll sigh at the sound of the train whistle, gawk at the coal-burning, steam-belching machinery and then squint into the distance like Clint Eastwood, the better to see the black locomotive chug around a distant curve.

On my ride, I shared one of the train’s open gondola cars with a man from Texas making his 15th trip; his son, a college freshman making his 10th trip; a German couple who wore all sorts of Harley-Davidson insignia and spoke no English; a tall Frenchman whose red sweater kept sneaking into the corners of my photos; and a professorial man from altitude-challenged Holland, who gave voice (in English) to what everyone should have been thinking.

“What an amazing landscape!” he said.

We glided alongside the river, passed stands of aspens, inched over high and low bridges, all the while climbing until we were 400 feet above the river and snowy peaks dominated the skyline. At Tank Creek, we paused while the engineer blasted steam from the locomotive. By the time we reached tiny, touristy Silverton (population 628), we’d nearly drained our camera batteries and gained almost 2,800 feet of elevation.

About Silverton: It’s a town out of time, surrounded by snowy peaks and dominated by Old West storefronts painted in rainbow colors. In the Train Store, railroad souvenirs. In the Storyteller Indian Store, jewelry. In the Eagle’s Nest, leatherwork.

I got to spend only three hours there (and came this close to buying a $39 leather wallet with an inset buffalo nickel), but I can understand why some locals are eager to see mining rise again. Without it, just about everything depends on the whims of tourists.

I had arranged to take a bus back to Durango (it’s faster than the train). But my thoughts kept drifting back to the Baker’s Bridge area, on the river about 14 miles above Durango.

Why? Upstream, the U.S. Geological Survey has found old mines leaking a stew of chemicals into the Animas, reducing fish and bug populations, and the Animas River Stakeholders Group has acknowledged elevated zinc concentrations at Baker’s Bridge. Yet from the tracks, it still looks perfect.

The water roars and hisses far below. The tall trees huddle ‘round, backed by snowy mountains. Local kids dare each other to leap into a swimming hole nearby.

You’ve probably glimpsed this spot in “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969). This is the cliff where the posse seems to have the outlaws cornered, the moment when Sundance confesses he can’t swim and Butch tells him the fall will probably kill him anyway. Then the two make their death-defying leap.

The West of old, the West of movie myth and the imperfect West we now live in — sometimes, they’re three different places. And sometimes they all come together in a moment on a train.

_______

Across the centuries in Durango, Colo.

60 million years ago

Rocky Mountains begin to rise at the close of the Mesozoic era. In southern Colorado, the San Juan Range becomes steep and rich in minerals.

550

The first signs of human habitation appear in the Mesa Verde area, about 40 miles west of the valley where Durango, Colo., will eventually grow. Archaeologists label these people Anasazi, though the National Park Service now prefers to call them Ancestral Puebloan.

1150-1300

The Ancestral Puebloan people farm, gather, hunt and build hundreds of cliff dwellings. Then amid signs of drought and dwindling resources, they walk away, migrating south to lands that will become New Mexico and Arizona.

1876

Colorado wins statehood.

1880

Town of Durango is founded by the Denver & Rio Grande Railway, headed by Gen. William Jackson Palmer.

1881

The D&RGR begins building a 45-mile Durango-Silverton line, laying narrow-gauge tracks that allow for sharper curves than standard tracks. Besides blasting tons of rock to make room for tracks on mountainside ledges, construction crews build 32 bridges.

1882

Hauling gold, silver and other precious metals from high-country mines, the train begins operating between Durango, about 6,500 feet above sea level, and Silverton, 9,305 feet.

1880-1894

The railroad hires photographer William Henry Jackson to shoot promotional pictures of the train and scenery along the Animas River. In a move that will be copied by millions of travelers, he also makes a trip to shoot the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde.

1906

Mesa Verde becomes the country’s 10th national park.

1947

The Silverton line, long known for its scenery, begins carrying tourists — 3,444 for the year.

1950

“A Ticket to Tomahawk,” featuring a bit part by an unknown Marilyn Monroe, is among the first of dozens of Hollywood films to shoot along the route. Later come “Around the World in 80 Days,” “How the West Was Won” and “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

1962

With the mining industry fading, the railroad, now known as the Denver & Rio Grande Western, seeks permission to stop service to Silverton. The feds say no.

1981

The D&RGW finally finds a buyer for the line, now known as the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. Citrus grower and train enthusiast Charles E. Bradshaw takes over for $2.2 million.

1989

A massive roundhouse fire makes headlines across the country, but the six operable locomotives survive.

1991

Silverton’s last major mine closes.

1994

The Animas River Stakeholders Group forms to begin work with federal agencies to reduce toxic waste left by mining companies. (As of early 2014, however, four “orphan” mines continue to leak iron, zinc, cadmium, copper and other toxins into the upper Animas River.)

1990s

Durango-Silverton passenger traffic reaches about 200,000 yearly (where it remains). The line is taken over by American Heritage Railways, which also operates the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad.

2002

The Missionary Ridge Fire consumes more than 72,000 acres north of Durango, killing one firefighter, destroying 56 homes and leaving burn patterns still visible on the slopes of the Animas Valley.

2002

Silverton Mountain, a skiing and snowboarding resort, opens outside of town. Once dependent on mining, Silverton now counts heavily on rail fans and extreme skiers.

Sources: “America’s Railroad: The Official Guidebook” by Robert T. Royem; National Park Service, www.nps.gov; Durango Area Tourism Office, www.durango.org; Durango Mountain Resort, durangomountainresort.com; Silverton Mountain, silvertonmountain.com; Environmental Protection Agency, 1.usa.gov/1hSshoG.

_______

A river runs through Colorado guide’s daily hustle

Play hard, work hard, repeat. This is Charlie Fox’s life.

“We call it the Durango hustle,” he says, steering a raft down the Animas River one May morning.

This, by the way, was work. From May through September, Fox is on the water daily as a river guide for Outlaw Tours, angling to get his customers soaked but not submerged at Smelter Rapid.

“I just can’t imagine living in a city without a river,” he tells me later.

The same goes for doing the same job year-round. In winter, he teaches snowboarding and helps paraplegics learn to use wheelchair skis.

This perpetual scramble is a way of life for thousands of young people in gorgeous, pricey, outdoorsy towns across the West. They love sports and nature so much — and value indoor work so little — that they craft their lives to maximize time outside.

If you’re one of their customers on a bike ride, a raft trip, a kayak expedition or a challenging hike, it’s natural to daydream about a life so in tune with the natural world. But if you’re one of these hustlers, life isn’t so simple.

While visitors tuck into premium steaks at the Ore House in downtown Durango, the river runners are more likely to be at Tacos Nayarit on Main and 25th, where you can get three tongue tacos for $6.50. And Fox, at 37, has been doing this longer than most.

He grew up about 200 miles southeast in Los Alamos, N.M., and came to Durango in 1997, planning to study at Fort Lewis College. He never finished — he calculates he’s two units short of a political science degree. But there’s a roof overhead, and in the warmer months, he does a lot of two-hour and half-day trips on the Lower Animas (where the city recently resculpted the water’s path near the Class 3 or 4 Smelter Rapid to make for better river-running). When he can, he gets to the Piedra River (where there’s usually Class 4 water) or the Upper Animas (often Class 5).

But raft and snowboard work covers only so much of the year. In between, Fox does landscaping, works as a bouncer and washes windows. For three years, he worked behind the counter of a liquor store, but he’s dropped that in favor of a bartending gig in an upscale club at the Durango Mountain Resort.

It’s a good thing he’s single, Fox concedes, because the old guide’s joke is true:

Q: What’s the difference between a large pizza and a river runner?

A: A large pizza can feed a family of four.

If you get him off the river for a conversation, Fox seems like a man on the brink of a big change. “I’m a dinosaur,” he says. Completing those last two college units “is something I think about every year. Maybe this year.”

But then the moment passes and the river begins to regain its grip. “In some capacity, I’ll always do it,” Fox says. “It’s fun. You meet people.

“And a bad day on the river beats a good day in a shoe store, I can tell you that.”

_______

At Mesa Verde National Park, step back into ancient Pueblo times

It’s a 90-minute drive from Durango, Colo., to Mesa Verde National Park. Do it — especially if it’s summer, when you’ll have a chance to climb among the park’s cliff dwellings.

After all, you probably won’t be in this thinly populated western Colorado neighborhood again soon. This remote location is why, even in busy July, the park tops out at about 3,000 travelers a day — about one-eighth the traffic seen at the Grand Canyon.

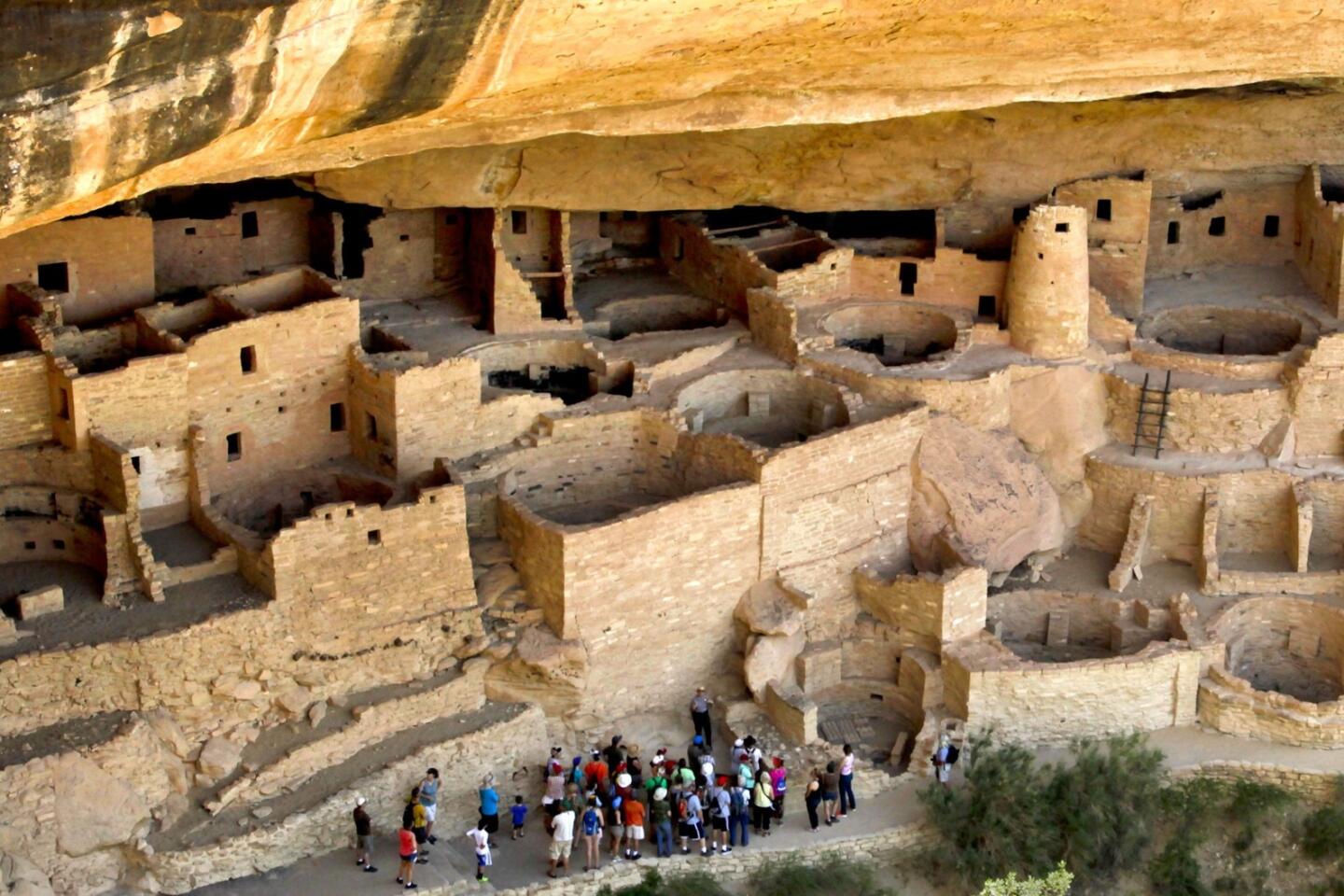

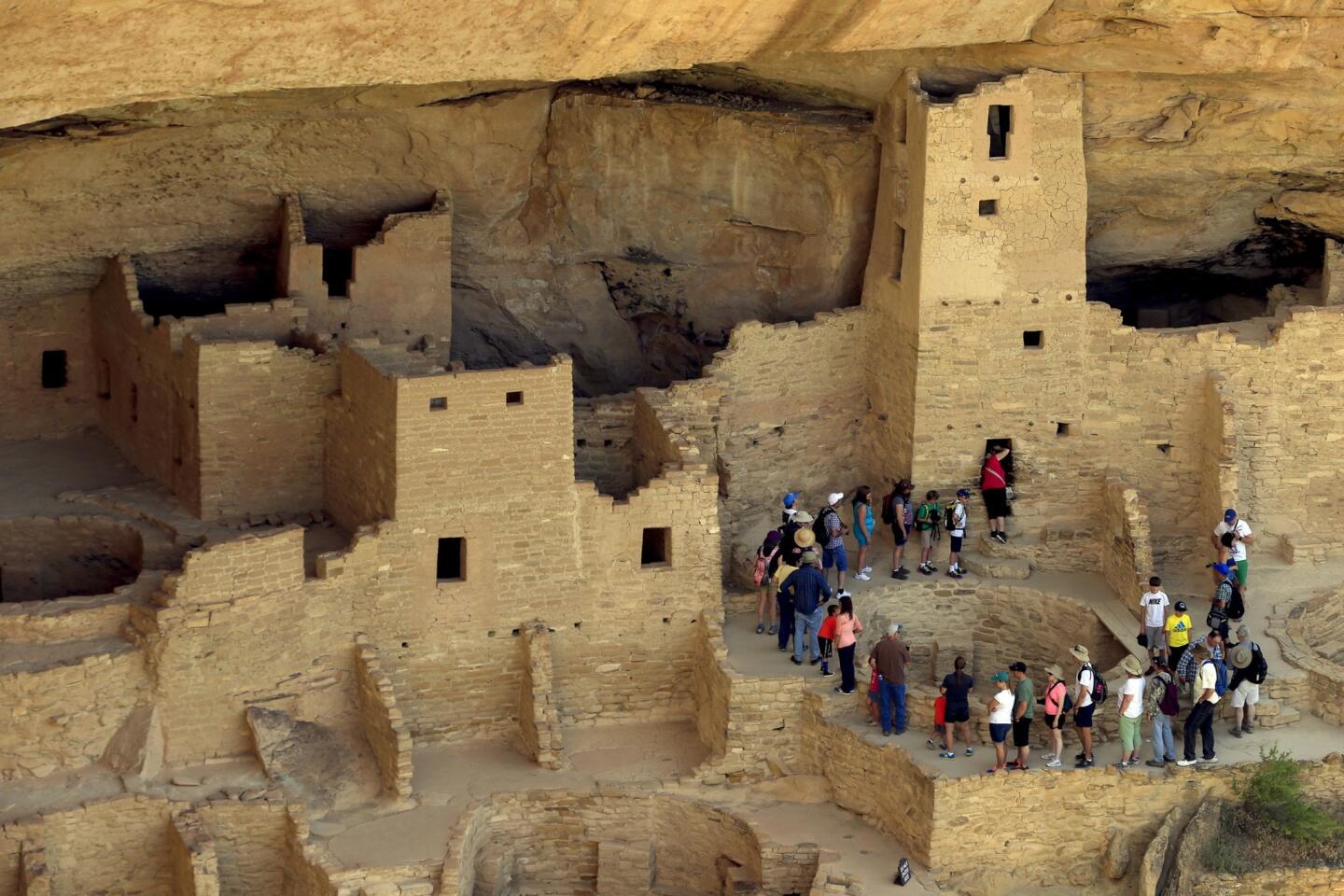

But Mesa Verde’s main attractions — more than 600 cliff dwellings, many dating to the 13th century — are a sight that won’t leave you any time soon. In fact, you may be too busy feeling like Indiana Jones to hear the ranger tell you that this was the first U.S. national park (1906) devoted to cultural history — something made by mankind — rather than natural history.

Then again, if you’re afraid of heights or tight spaces, some spots will be downright alarming.

The park is full of ruins, trails and austere scenery, including the Long House and Step House on Wetherill Mesa, as well as Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum, which tells how the Ancestral Puebloans (also known as Anasazi) lived and farmed on mesa tops for hundreds of years before moving to the cliff dwellings below, then moving on to New Mexico and Arizona in about 1300.

If you’re fairly fit and untroubled by heights, I recommend the Cliff Palace and Balcony House tours, which are led by rangers in warmer months. To reach those cliff dwellings, you drive 21 miles from the northern entrance to the center of the park, crossing stark territory (7,000 to 8,500 feet above sea level) whose pinyon and juniper forests have been repeatedly scarred by fire. Between 1996 and 2003, five fires, all sparked by lightning, together burned more than half the park’s 52,000 acres.

Just about the time you start wondering why you came so far to see such a bleak scene, you’ll arrive at the heart of Mesa Verde, leave your car in a lot and step down from the top of the mesa into the late 1200s.

Cliff Palace is the park’s largest cliff dwelling, with 150 rooms and 23 kivas (rooms used for religious rituals). It’s thought to have housed about 100 Ancestral Puebloans.. The structures are made of sandstone blocks, mortar, plaster and wood beams.

Though the quarter-mile path includes more than 100 stair steps, four ladders of 8 to 10 feet each and plenty of steep drops without railings, it’s less physically demanding than some others. If you’re not up to the tour, go to the outcropping of rock where groups meet before descending, and you’ll find a breathtaking view of Cliff Palace under the lip of a sandstone ridge.

Balcony House is a wonder too: Forty rooms hanging above Soda Canyon. To walk among the ruins, you’ll need to descend a 100-foot staircase, ascend a 32-foot ladder, crawl through a 12-foot-long tunnel that’s about 18 inches wide, then climb on about 60 feet of ladders and steep steps that are carved into the rock face of a cliff.

There are no height or age restrictions for tours, but the National Park Service discourages adults with heart or respiratory problems and says “children must be capable of walking the extent of the trails, climbing ladders, and negotiating steps independently.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.