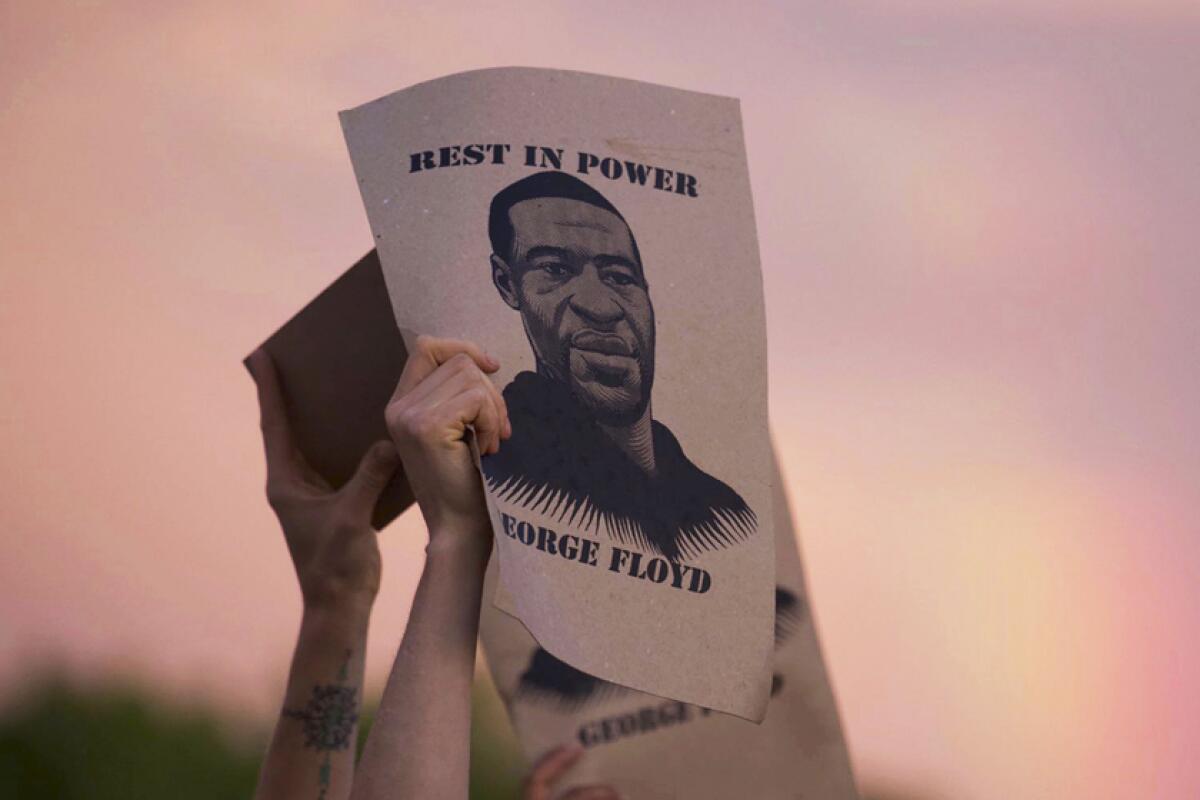

George Floyd protests spread to smaller, mostly white towns

- Share via

Norfolk, Neb., is a quiet, conservative and predominantly white city of 24,000 people where public protests are rare, except for an annual rally against abortion. So when about 300 people gathered on a busy street corner last weekend to voice their outrage at the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, residents took notice.

The rally was peaceful, but the fact that it happened at all illustrates how far the movement to protest police brutality and discrimination has spread, fueled by social media and the persistent but less visible racism that minorities say they experience in small towns.

“It was important to do it, especially in the middle of Nebraska,” said rally organizer Eduardo Mora, who lives in a neighboring town. “Are we going to wait for a police brutality incident to happen here? We shouldn’t wait for there to be a life taken.”

While the rallies in major cities nationwide have grabbed headlines, people living in smaller and mid-sized cities have also raised their voices to call for change. Some of those protests have turned violent.

In Sioux City, Iowa — population 83,000 — five officers were injured in a confrontation with protesters, and several squad cars were damaged. Officers used pepper spray on the crowd after some of them pelted the officers with rocks.

A rally in Grand Island, Neb., drew more than 100 people to march in solidarity with activists for social justice. Officials reported that troublemakers in a passing car sprayed the protesters with a foul-smelling liquid that might have been urine. The protest in the city of 51,000 people was otherwise peaceful.

Local officials in Farmington, N.M., were surprised when 250 protesters showed up for a peaceful rally in front of a mall. The town of 44,000 sits on the border of the Navajo Nation, and the demonstration attracted members of the American Indian Movement and other activists.

“It was larger than we expected,” said Nicole Brown, the Farmington Police Department’s public information officer. “We haven’t really had many large protests. Most of [the previous ones] were small, with maybe 50 people.”

A protest organized by church leaders drew a diverse crowd of about 100 people to city hall in Rome, Ga. The event focused on demanding justice for Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old black man who was chased down and fatally shot in Georgia while jogging.

“Overall, our protests have been very positive,” said Kristi Kent, a city spokeswoman. “We haven’t seen any types of violence or negativity around them.”

Mayor Josh Moenning said public demonstrations were rare in Norfolk, Neb., but that he understood why they had gathered, and he praised them for doing so peacefully.

Even though Norfolk hasn’t had any notable conflict between minorities and police, Moenning said many non-white residents said they’d experienced racism in the community. Floyd’s killing was a painful reminder, he said.

Nebraska school officials have seen numerous instances over the years of fans shouting racist taunts at high school sporting events. The University of Nebraska faced some criticism in 2018 for not taking action against a student who identified himself as a white nationalist. And in Norfolk, racial tensions flared in 2014 when a resident entered a July 4 parade with an outhouse mounted on a float labeled, “Obama Presidential Library.”

“Like any community, yes, we have a history of racial challenges,” Moenning said. “I think the best way we can deal with those challenges is to talk about it in an honest way and seek to build relationships.”

The protests even in small towns reflect long-simmering anger over implicit discrimination, such as when police officers watch minorities closely, said Patrick Jones, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln history and ethnic studies professor. Police shootings of black men only make it worse, he said.

“We’ve reached this tipping point with George Floyd,” Jones said. “Frustration has continued to build with each new incident, and this was the spark. But it’s really rooted in a broader set of injustices.”

The small-town rallies come as no surprise to Cynthia Willis-Esqueda, a civil rights activist and University of Nebraska-Lincoln psychology professor who studies the effects of discrimination on minorities. Willis-Esqueda said social media had made it a lot easier to publicize and organize rallies, and the coronavirus pandemic has played a role too, driving up unemployment and economic anxiety among minorities who are already struggling financially.

“It’s not as if people in large cities are the only ones who have been affected,” she said. The protests “aren’t just a response to what has happened, not just in their immediate community. It’s a response to what has happened in the United States in general.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.