John Robinson, coach who led USC to national title and Rams to two championship games, dies at 89

- Share via

John Robinson, who coached his signature run-oriented USC football team to a national title and took the Los Angeles Rams to two NFL conference championship games, has died. He was 89.

Robinson, whose USC teams won four Rose Bowls in his two stints with the Trojans, died Monday in Baton Rouge, La., of complications from pneumonia, USC announced.

Robinson succeeded the legendary John McKay at USC in 1976 and continued the Trojans’ winning tradition for seven seasons. The Rams lured him to pro football in 1983 and he led the franchise to numerous playoff appearances and the brink of two Super Bowls before returning to USC a decade later. His last coaching job was at Nevada Las Vegas, where he temporarily revived a moribund program.

After his coaching career ended in 2004, Robinson worked as a broadcaster and a volunteer assistant football coach at his grandson’s high school in San Diego County. He returned to USC as a fundraiser in 2011. In 2019, he served as a consultant for Louisiana State’s national championship team.

“I enjoyed it,” Robinson, when asked how he would like to be remembered, told The Times during an interview in May 2024. “And I think that’s the big thing — that when you get a job you enjoy it.

“You always think, ‘God, I could have done that better.’ But, you know, you have to be satisfied with what you did. I enjoyed the players just tremendously, and there were so many good ones.’”

The affable Robinson, a 2010 inductee to the College Football Hall of Fame, was known as much for his easygoing manner and sense of humor as for his tailback-dominated football teams.

“He was as cheerful as a sunrise,” Times columnist Jim Murray wrote in 1982. “Football coaches tend to be Machiavellian in character, but Robinson was more like a country doctor healing the sick in exchange for fresh eggs.”

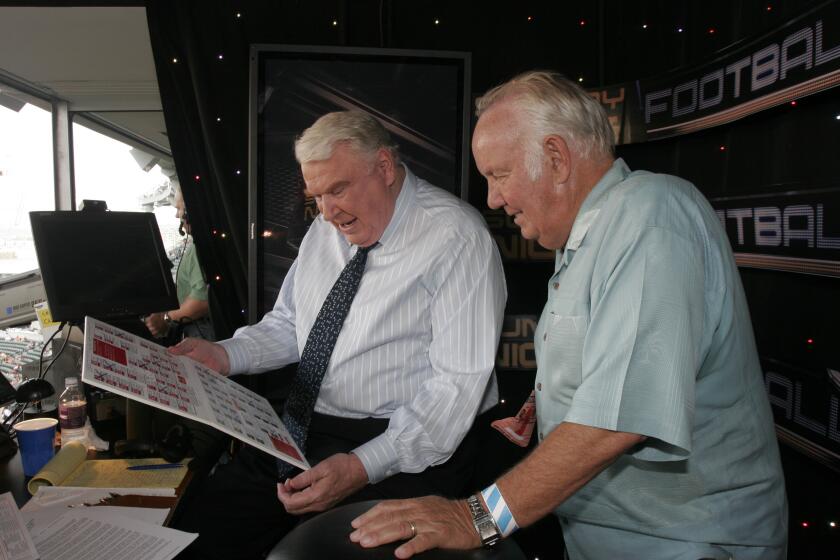

John Robinson and John Madden had known each other since the fifth grade. John Robinson talks about his relationship with the Hall of Fame coach-broadcaster.

Robinson made no apologies for his approach. His goal was to win — and to have fun doing it.

“Coaching has that image of obsessed men driven to a point where they’ll destroy their lives,” he told The Times’ Mal Florence in 1981. “I’ll be damned if I’ll destroy my life.”

Robinson compiled a record of 104-35-4 in a combined 12 seasons at USC. Only McKay and Howard Jones won more as the Trojans’ coach.

He coached 153 games for the Rams — the most in franchise history — and compiled a 79-74 record, including a 4-6 record in the playoffs. His 79 victories, including playoff wins, were the most in Rams history until Sean McVay eclipsed his record in 2024.

Robinson, who grew up in the Bay Area and played football at Oregon, crafted offenses built around strong running games.

Heisman Trophy winners Charles White and Marcus Allen and Heisman runners-up Anthony Davis and Ricky Bell were among the running backs Robinson tutored as an assistant and head coach at USC. With the Rams, Eric Dickerson and White won NFL rushing titles under Robinson.

Among the other All-Americans who played for Robinson at USC: offensive linemen Marvin Powell, Pat Howell, Brad Budde, Anthony Munoz, Bruce Matthews and Tony Boselli; linebackers Clay Matthews Jr., Chip Banks and Chris Claiborne; defensive backs Ronnie Lott and Dennis Thurman; and receiver Keyshawn Johnson.

But Robinson’s career was not without controversy.

The then-Pac-10 Conference banned Robinson’s Trojans from playing in a bowl game after the 1980 season because of violations, including the enrollment of more than 30 USC athletes in a speech class for which they were given credit without attending.

In 1982, the NCAA banned Robinson’s USC team from bowl games and from appearing on television for two seasons for various violations, including assistant Marv Goux’s scalping tickets and funneling cash to players.

With the Rams, Robinson was referenced in one of the most memorable quotes in Los Angeles sports history. Dickerson, campaigning for a new contract in 1987, said “Let him run 47-gap,” referring to a play frequently called by Robinson and suggesting his ball-carrying was harder than it looked. The disparaging comment helped trigger Dickerson’s trade to the Indianapolis Colts.

John Alexander Robinson was born in Chicago on July 25, 1935. His father worked as a construction engineer and the family moved to Provo, Utah, when Robinson was 6. The family eventually settled in Daly City, south of San Francisco.

It was in the Bay Area where Robinson met John Madden, another future Hall of Fame coach, in elementary school. The boys attended different high schools, but the friends’ passion for football and coaching carried both to successful careers.

NFL star John Madden, who reached the top of his profession in coaching, announcing and video games, died unexpectedly Tuesday morning at age 85.

Robinson played football and baseball at Junipero Serra High in San Mateo before moving on to Oregon, where he was a reserve receiver from 1954-58.

“I got so little playing time at Oregon,” he joked, “the zipper on my warm-up jacket rusted shut.”

Robinson joined the Oregon staff as a graduate assistant in 1958 and remained with the Ducks under coaches Len Casanova and Jerry Frei through the 1971 season. That’s when McKay, an Oregon assistant during Robinson’s time there, hired Robinson as an offensive backfield coach for the Trojans.

Robinson helped USC win national titles in 1972 and 1974 before Madden persuaded him to join his Oakland Raiders staff.

“As kids, we always talked about one of us coaching someday and hiring the other guy,” Madden told The Times’ Dwight Chapin in 1981. “I tried to hire John for the Raiders three times. Once he’d been promoted at Oregon and the other time he’d just joined USC. But I finally got him.”

Robinson stayed in Oakland for only one season.

In November 1975, with McKay headed to the NFL to coach the expansion Tampa Bay Buccaneers, USC chose the 40-year-old Robinson as his successor.

Robinson was excited about running his own team and returning to the pageantry of college football, which in USC’s case featured Traveler, the Trojans’ equine mascot who sprinted along the sideline.

“I liked it on the Raiders,” Robinson quipped, “but I really missed the horse.”

Robinson’s USC debut did not go as planned, the Trojans losing to Missouri in the 1976 opener at the Coliseum. But USC won its next 10 games, capping the season with a Rose Bowl victory over Michigan.

Two years later, the Trojans again defeated Michigan in the Rose Bowl to finish 12-1. USC was voted No. 1 in the final United Press International poll, splitting the national title with Alabama, which lost to the Trojans early in the season, 24-14, but was voted No. 1 in the Associated Press poll.

The Trojans also won the 1980 Rose Bowl, defeating Ohio State to finish the 1979 season with an 11-0-1 record. USC finished second behind Alabama in both polls.

Robinson’s success attracted the NFL. In January 1982, he turned down an offer to coach the New England Patriots. That November, with the Trojans 7-3 and preparing to play Notre Dame, he announced that he would resign after the season to become a senior vice president for university relations.

“I’d like to go out with the seniors Saturday and say, ‘This is my last and final round,’” he said. “The theme would be: ‘Win one for the fat guy.’”

The Trojans defeated Notre Dame 17-13, giving the portly Robinson a 67-14-2 record at USC.

At a news conference earlier that week, Robinson had been asked if he would consider coaching in the NFL.

“No, I don’t think so,” he said. “I’ve committed myself to another type of life.”

But less than three months later, on Valentine’s Day in 1983, owner Georgia Frontiere tapped Robinson to coach the Rams.

She called Robinson “the perfect package. Everything we want.”

Under Robinson, the Rams made the playoffs six times in his first seven seasons.

In 1985, they won their division and reached the NFC championship game before losing to the eventual Super Bowl champion Chicago Bears. Four years later, they returned to the conference title game but lost to the San Francisco 49ers, who went on to win the Super Bowl.

The next season, however, the Rams fell to 5-11. In 1991, they were 3-12 and had lost nine consecutive games when Robinson announced his resignation a few days before the season finale.

“I’m going to take some time off and sit down and enjoy my life and look ahead to what’s coming,” he said. “Whether I stay in coaching or not, I’m not sure.”

Robinson returned to USC in January 1993, less than a month after former coach Larry Smith and the Trojans lost to Fresno State in the Freedom Bowl, which was played in Anaheim until it was discontinued after the 1994 season.

But Robinson could not duplicate his previous success. The best of his five seasons came in 1995, when the Trojans defeated Northwestern in the 1996 Rose Bowl to finish 9-2-1.

Robinson was fired in December 1997 and replaced by Paul Hackett, USC holding a confusing news conference on campus and Robinson holding his own at a downtown hotel. Robinson said Athletic Director Mike Garrett had left him a phone message, “saying I had in fact been replaced.” Garrett said he had tried several times to reach Robinson but Robinson never called him back.

“We obviously had a falling out, but when I was fired I wasn’t coaching very good,” Robinson told The Times’ T.J. Simers in 2011. “In time, we got back together and when you look at his resume it was pretty damn good.”

Robinson returned to coaching at Nevada Las Vegas in 1999, taking over a program that had won only six games in the previous four seasons, including a 0-11 finish in 1998.

He guided UNLV to a 2000 Las Vegas Bowl victory to cap an 8-5 season. After a 0-4 start in 2004, he announced he would resign effective at the end of the season. He finished with a 28-42 record in six seasons with the Rebels.

Robinson concluded his career at LSU when Ed Orgeron, a former USC assistant and interim head coach, hired him as a consultant.

Robinson is survived by his wife Beverly; his four children, daughters Terry Medina and Lynne Sierra and sons David and Chris; two stepchildren, Jennifer Bohle and Jeffrey Ezell; and 10 grandchildren.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.