- Share via

CORVALLIS, Ore. — Jaylen Clark is making room for it in his mind. Alongside the trophies, medals, plaques, certificates and awards the UCLA guard has accumulated over a career spanning numerous youth and high school championships plus a trip to the Final Four will soon reside one improbable basketball memento.

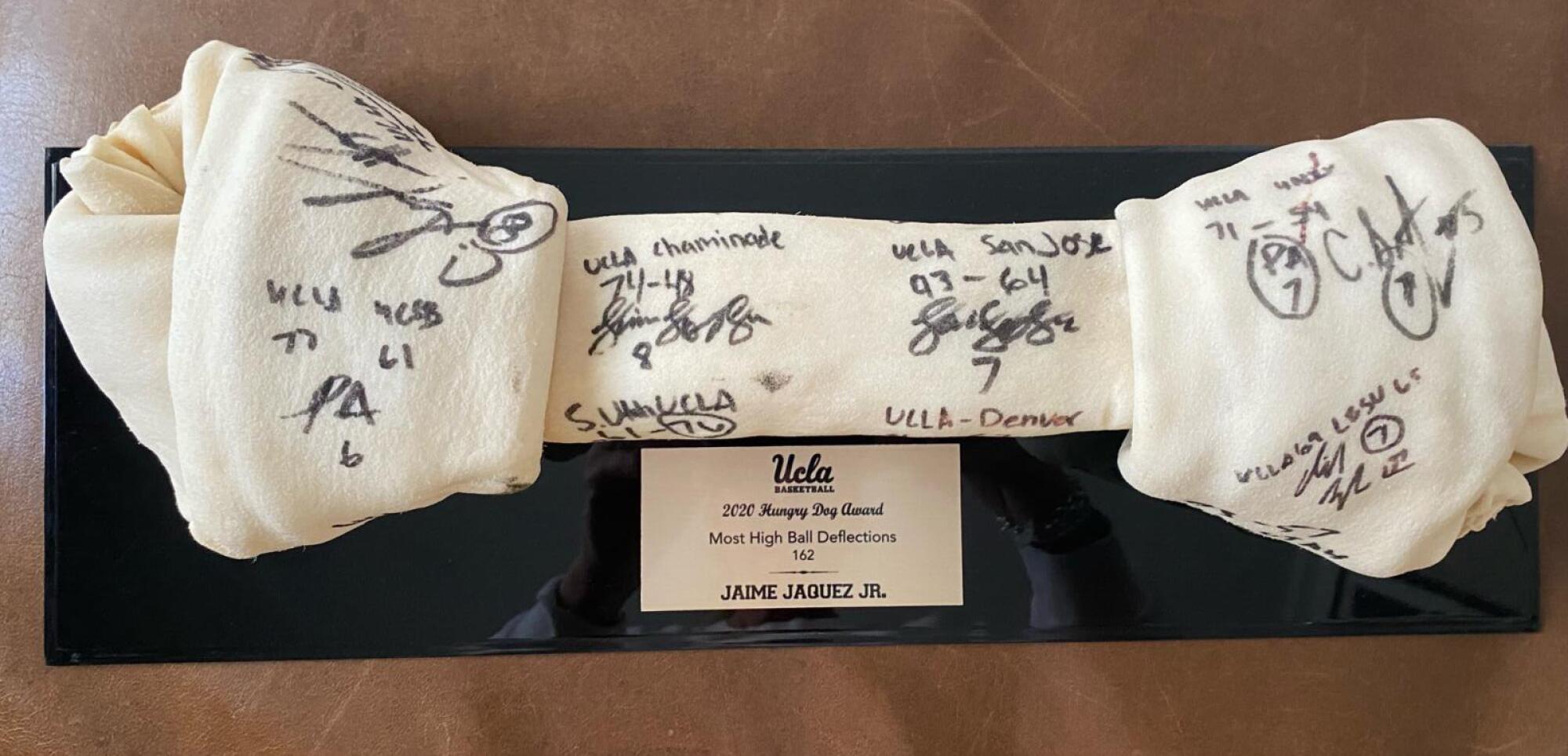

A 2-foot-by-6-inch rawhide dog bone.

It’s a Mick Cronin tradition going back to the coach’s days in Cincinnati. The Hungry Dog Award is signed by the player with the most deflections after every game. At season’s end, it goes home with whomever leads the team in being the biggest pest, instantly becoming a prized possession.

Jaime Jaquez Jr. enclosed the bones he won during Cronin’s first two seasons in Westwood in protective plastic cases. Clark, the runaway leader this season with 220 deflections — defined as steals, blocks, tipped passes and loose balls collected — has picked a prime spot in his apartment to showcase his bone. Meanwhile, Jaquez’s 149 deflections and David Singleton’s 105 have left them in a forlorn fight for second place, like Bing and Yahoo jockeying for position behind Google.

Being relentless to the extent that he is, earning himself the nickname the Man of Steal, Clark pointed out that this bone should be his third as a Bruin.

“If you go by deflections per minute,” said Clark, who averages one every 3.3 minutes of action this season, “I should have won it every year.”

A significant rise in playing time as a junior has ensured a breakthrough. It’s also left nearly every offense the Bruins have faced in tatters, like the ripped practice jerseys Clark regularly cycles through. Grabbing a piece of fabric is often the only way teammates can fight back against the disruptiveness that comes from Clark’s quickness, instincts and, well, doggedness.

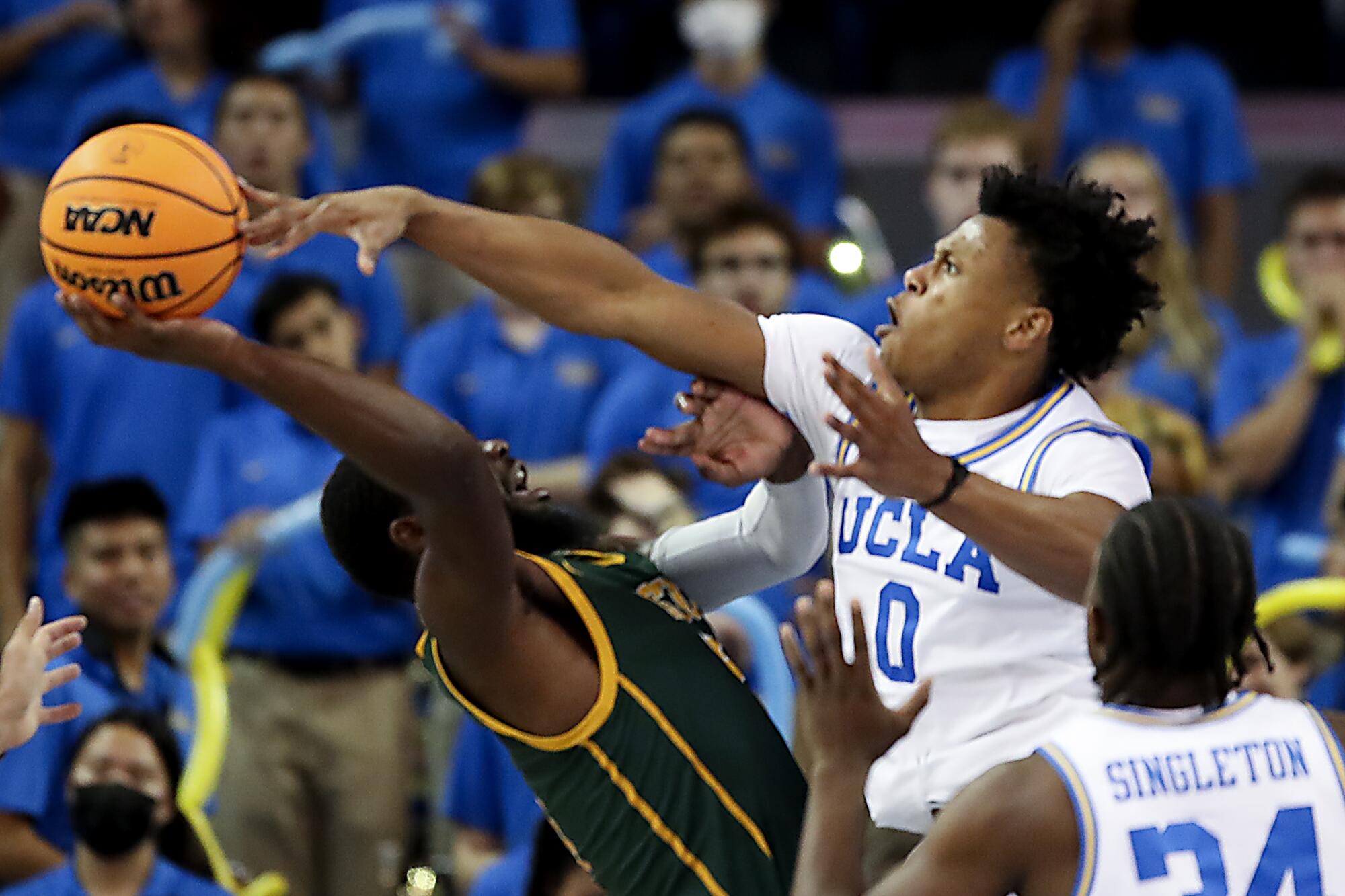

UCLA guard Jaylen Clark’s ability to anticipate where a ball is headed with the use of his quick hands and active feet to take it away make him a defensive menace.

“It’s well known in practice, like, if you want to give a dribble handoff, you don’t go to his side,” Jaquez said. “And then, when it’s on the opposite side, he’s very good at helping and trying to read skip passes and things like that.”

Leading the Pac-12 Conference with an average of 2.64 steals going into the seventh-ranked Bruins’ game against Oregon State on Thursday evening at Gill Coliseum, Clark wants to make his bones about more than bones. He’s also pursuing UCLA’s single-season steals record of 95 set by Jordan Adams nine years ago, needing 38 steals to get there with at least 10 games left.

Though it may require him to accelerate his pace or have the Bruins go on a deep postseason run, Clark can see it happening.

Remember, anticipation is his specialty.

The kid who defended like crazy wasn’t a hot college prospect by the time Cronin settled into his courtside seat inside a high school gym to see him play for the first time.

Only a handful of major conference schools had offered Clark a scholarship, many others skeptical about his slowly developing offensive game.

The bald coach, in his first season at UCLA, wanted a stopper he could build his defense around. An inconsistent jump shot wasn’t off-putting in the least. What mattered was that this wildly athletic guard chased every loose ball and followed his steals with breakaway dunks.

“He was breathing fire,” Cronin said, “from the time he saw me sitting in the front row.”

Defense wasn’t always his top priority. Like most young players, Clark fancied the offensive highlight. His attitude changed when he joined a stacked club team featuring eventual NBA first-round draft picks Evan Mobley and Onyeka Okongwu, among other older and more decorated players. Clark’s father, Cornelius, warned him that he’d never get to play if he didn’t follow one rule.

“You play defense,” his father told him, “you’re going to force your way onto the floor.”

Clark kept that mindset while starring at Etiwanda High under the guidance of coach Dave Kleckner, who had previously molded another future Bruin into a lockdown defender. Remember Darren Collison? The undersized point guard had also faced questions about being a UCLA-caliber player before going on to play in three Final Fours and spend a decade in the NBA.

Kleckner gave those questioning Clark’s ability at the next level the same spiel he had delivered about Collison.

“People asked, ‘Is he good enough?’ ” Kleckner recalled. “And I was like, ‘Yeah! You guys, this kid, he wants it so bad, any obstacle that he comes across, he’s going to meet it head-on and he wants it so bad he’s going to do whatever it takes to get it.’ ”

It helped that the 6-foot-5 firebrand possessed a 6-7½ wingspan — the longest among UCLA’s guards — to go with his speed and go-go drive. Those traits allowed Clark to defend every player on the court, from jitterbug point guards to beanpole centers. He stayed in front of even the speediest counterparts, hounding them with his active hands to swipe the ball or at the very least prevent them from making the easy pass.

Jaylen Clark’s explosiveness and intuitiveness make him among the top defenders on a UCLA team that often struggles in that department.

His versatility allowed him to roam the court like a free safety in football, anticipating passes that he either intercepted or tipped to tally another deflection in his pursuit of the deflections bone.

Kleckner’s defensive principles mirrored those Clark would use under Cronin, making his transition to college as easy as all the points he scored on fast breaks. Both coaches favored forcing players toward the baseline and used similar help rotations.

Their No. 1 priority was already embedded in Clark’s basketball DNA.

“If you don’t guard anybody,” Cronin said, “you’re not going to play.”

There are many ways to go about it.

Tyus Edney piled up steals by studying the guy he was guarding, the onetime UCLA point guard comparing the first few minutes of each game to boxers feeling each other out at the start of a match. Did his man prefer going to his left or right? Was his dribble a bit high? What would he do if Edney swiped at the ball a certain way?

“You see, like, if you do something and he crosses over, now you’re like, OK, that’s his tendency,” said Edney, whose 11 steals against George Mason in December 1994 remain a Pac-12 record. “I’m going to go to his crossover, so now you can sit on it once and maybe he relaxes and you go at him and poke it away and get a steal. Just little stuff like that. That’s the game within a game between point guards.”

The most iconic shot in UCLA history — by Tyus Edney with 4.8 seconds left in a 1995 March Madness game — originated on a makeshift driveway court.

Collison relied heavily on hours of film study with UCLA coach Ben Howland. Developing a familiarity for where teams liked to go with the ball, Collison would often beat intended recipients of passes to their spot. All he had to do at that point was grab the ball.

Over the last few summers, Collison worked with Clark at a training facility in Irvine, developing all aspects of his game. Collison taught his protege to get up on his man, know when he’s going to change hands and take something away so that when he tries to counter, Clark can be ready. They’ve even worked on Clark’s post-up moves.

Stuck in a shooting slump the last few weeks, Clark might want to remind himself that earlier this season he became the only NBA, WNBA or Division I men’s or women’s player in the last 20 years to collect at least 15 points, seven rebounds and seven steals while making all seven shots during a rout of Sacramento State.

“He really doesn’t have a weakness in his game when that jump shot’s falling,” said Collison, whose 231 steals as a Bruin trail only Earl Watson (235) on the school’s career list since it started tracking the statistic in 1978.

The five players with the most steals in UCLA history are all point guards, making Clark something of an outlier. As a hybrid shooting guard-small forward, he spends less time guarding the ball than anticipating where it might be headed. His magnetic pull toward dimpled leather reminds Edney of Jason Kidd, the former California star who set the Pac-12 record with an absurd 110 steals during the 1992-93 season.

“He’s just everywhere,” Edney said of Clark. “It seems like he’s a ball of energy in covering ground.”

A lot of Clark’s steals come off trapping and double-teaming, his lively arms and feet making him tough to get around. He’ll also look for screens when he knows players intend to curl around for a pass that often finds its way into his hands. And good luck with dribble handoffs in his vicinity. Clark usually blows those up, leading to another signature on the bone.

Seeing the smallish bone his team had been using earlier this season, Cronin asked for a bigger one.

“I was like, ‘What the heck’s that?’ ” Cronin said.

Jamiel “Jam” Liu, a team manager, found a larger bone on PetSmart’s website before a support staff member went to buy it. The bone goes everywhere the team does, accompanying the Bruins this week to the Pacific Northwest.

Its ultimate destination is already known, at least in Clark’s mind.

“I’ve just got to get a case,” Clark said. “Jaime’s not going to have another one.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.