- Share via

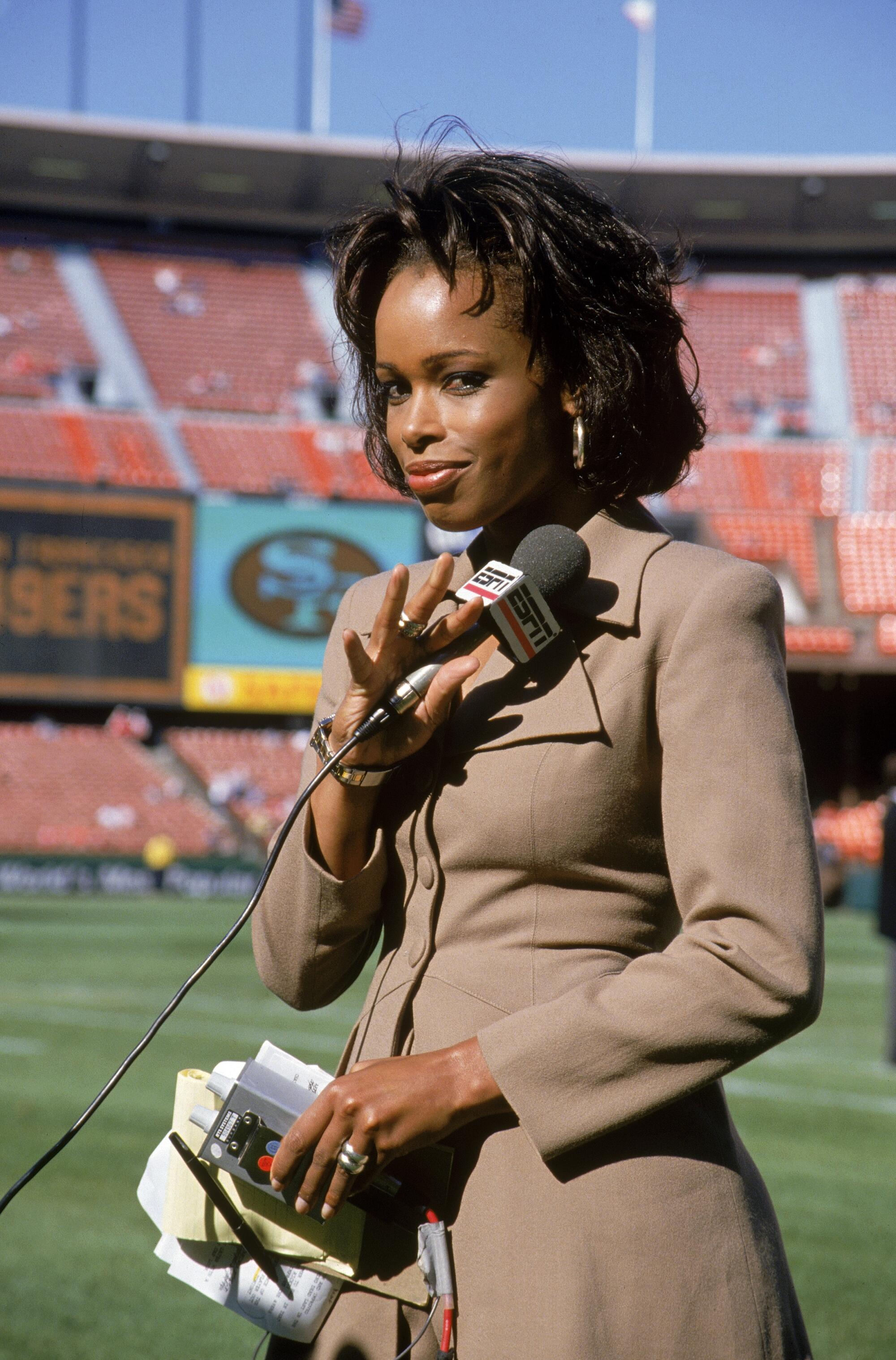

She sat there, all smiles and shell tops, without the benefit of a Fox flag or microphone to shield herself, painted into a mundane conference room that’d heard the stale chatter of production planning for hours. Ah, look at her, trying to hide it, offering me winks and cheekbones instead of succumbing to her own fragility. As much as she fought, she was shivering from her fingertips due to the ice-blue Pacific chill. It was spooky, she was offering me tea, and pretending not to feel the bite of the brittle, even a few dizzying doors above Pike Place. If I didn’t believe the stories before I met her, I certainly did then. It was as true as all the players and producers, coaches and coordinators had said for three decades: There may not be a tougher person in pro football than Pam Oliver.

Though she loves to present like any other, round-the-way gal: at 62, she remains remarkably regal — unyielding and unbending as one of the last striking figures of a pale Fox football team these days. So, please excuse me. From here on it’ll be, “Miss Pam,” ’cuz I don’t plan to disrespect the first lady of football. And you should be damn sure you don’t, either.

Football royalty, or not, the balance between being a commodity — enough that grown men on game days get weak in the knees and beg for pictures or young broadcasters compare you to anyone from Oprah to Gayle — and a professional is still difficult for Miss Pam to wrangle. “It’s weird when you become the story,” she tells me. Yet, Miss Pam remains surprised when I tell her there are still plenty of folks — aunties and mamas, jokers and bobos — all over this America who still draw a blank about the Black woman on the sidelines carrying Fox’s flag. That is, beyond the signature news hair and straightforward questions.

“Reaaaaaally?” she says, drawing out each of the vowels. She almost started to scoff at the idea that somebody don’t know Pam Oliver. She wriggles her nose, rolls her eyes and turns her face to the side, trying not to completely cast me off. “Ohhhhhkayyyy,” she winces. She was still deciding to let me into her orbit for even a second, likely wondering what she always does when the questions fly: what would the world possibly want to know about lil’ ol’ Pam from Dallas, Texas? But, she finally accepts what could be true. “I di–I did withdraw, some,” she said. “Two or three years ago.” While Miss Pam loves considering the psychology of why she’s been so adored and reviled all these years, she admits that she still doesn’t get our fascination with her.

“I’d always ask them, what’s different? What’s the angle?” she said, skeptically of the waves of public speaking requests thrown at her and the pressure from Fox to be more public in the last decade. It just wasn’t her style. To her, it felt like those raised hands only wanted to talk to her for one reason, and she was unwilling to go back to the moments that kicked her hardest in the teeth. Miss Pam was certainly resilient, but she was just as certainly no one’s fool.

“I grew tired of that same, old song and dance.”

Straight to the point, with no fuss at all. Her fearlessness was endearing. It reminded me of a phrase she’s taken a liking to that was inspired by Eleanor Roosevelt, one that she trotted out for years when life seemed to be getting the upper hand. She’d say it aloud and to herself when she needed it most, “No one can make you feel bad about yourself without your consent.”

Mary and John Oliver are long gone now, but they did leave with Miss Pam some unshakable lessons. Mary and John separated when Miss Pam was young, leaving her mother to pick up the burden of tending to her three daughters with all the might she had. Watching her struggle, Miss Pam understood what it truly meant to be a fighter. “I learned from watching her that you do what you have to do,” she says. “I watched her do whatever job she could take to take care of her girls and make sure we had all of the niceties and all of that.”

Every two years, they would move. Michigan. Washington. California. Until John’s Air Force career wound down and they nestled into a corner of northwest Florida. It was so unsettling that now into her 60s, she still can’t come up with an answer about her origin. “It’s hard for me now,” she says. “I’ve lived in Atlanta for 12, 13 years and when people ask where I’m from …” she doesn’t know what to tell them. “I say Atlanta only because I’ve got to feel like I’ve got roots somewhere.” Even then, how could a child even try to make friends? “That’s when I fell in love with sports,” she says.

Who needed someone else besides her sisters, her best friends in the world? Who needed nobodies when you had track, basketball, baseball and volleyball? She still likes to say she fell in love with the games like we all did: hook, line and sinker. Mary was a Cowboys crazy; so when Little Pam wasn’t admiring Wilma Rudolph’s stride or Althea Gibson’s serve, she held out hope of marrying Drew Pearson when he was done playing receiver for America’s Team.

Whatever environment she was thrown into, she decided long ago that she would never wilt. She’d always adjust. Pick herself up from the floor, wipe the tears from her eyes and get it together. She couldn’t tolerate seeing herself as anything less than mighty. “You know,” she says about the constant moving around. “I loved it, but it wasn’t always that way. There were times we’d move somewhere else,” and, she groaned, it was like “God, I have to start all over.” After enough moving, it became a routine. She built a habit of saying goodbye. The groans grew to excitement. “I had a fresh start. I could not reinvent myself, but if something didn’t go right at the previous stop, I made sure not to repeat those mistakes. It was a blessing and a curse. You learned to stand on your own two feet, you learned to put yourself in a position of not needing …”

People?

“You need people,” she admits. “But, I didn’t need to have a clique. I would ease in and have a couple of super close friends. None I stayed in contact with,” she laughs. Her husband, Alvin Whitney, has dozens of friends going all the way back to kindergarten. Miss Pam can’t stand the thought of that for herself. After the tears dried the first few times, her face learned to grow cold. “I was like, ‘Onto the next,’” she says. “You go through a brief mourning period, but my personality was: What’s next? Even at a young age, I felt like I was leaving one situation for another. How was I going to enter it, survive it and exit it? Because you know there’s eventually going to be an exit. There was a lot of saying goodbye and, for me, barely looking back. I barely looked back. Even when the professional thing started, I kept my friendships, but,” her mindset hadn’t changed. Two years and she was out. “That s— don’t work. God’s got a plan for you. And the circumstances,” she says. “They just are what they are.”

Thierry Henry struggled to translate his killer instinct as a player into the right coaching tone. He’s ready for another shot, but will anyone call?

Going from state to state and base to base following her father around the country left her in too few spaces without Black faces. “Growing up with the military, it was a predominantly white life,” she tells me. And the things she could treasure as a girl were few and far between.

The moments when it got lonely, when sports couldn’t provide what shrugging off friends didn’t allow, she was still searching. Aching for an image of someone who allowed her to believe in her own quietly kept dreams. As she inched toward teenage-hood, and Miss Pam was still a runt, she remembers running into whatever house they had in Dallas — before the big moves really started — right before the clock hit 6. She needed to hear the folksy jingle of the 6 o’clock news she coveted.

If she would do nothing else every night, she’d be sure to watch the glamorous Iola Johnson sit behind the desk at WFAA and do the news on Channel 8. If you were savvy enough to get in front of the tube back then, it was like watching Diana Ross sing. Before ninth grade, Little Pam couldn’t escape her own fanaticism. Track was giving her something to work on in her personal life as the family settled in Florida, but in the back of her mind: news was always there. Who wanted to be Walter Cronkite or David Brinkley when Carole Simpson’s layered, Black bouffant confidently sitting behind a “World News Tonight” desk on ABC could make any Black girl back then feel like she could be anyone she wanted in the world.

When she graduated from Niceville High, she decided she needed to dive first into a Blacker world than she’d been used to. She yearned to be in a place where Black history wasn’t relegated only to a day during Black History Month at school, or a place where she wasn’t just “pretty for a Black girl.”

“I get that retirement question all the time. ... It makes me f— crazy.”

— Pam Oliver

“I wanted diversity,” she says. “I really wanted the opposite of what I’d grown up with.” She thought about Florida State, but didn’t consider herself a good enough athlete, laughable for someone inducted into her college’s athletic Hall of Fame — twice — for running the 400 meter dash and relays. Deciding on a historically Black college, such as Florida A&M, “It was just the best thing that ever happened to me. I believe things happen to you. I needed to understand that the world wasn’t…” she pauses. “I needed to know more about Black history and myself. I had to get away. I knew that the world I’d grown up in wasn’t legit. It was unrealistic.”

One of the many schoolings she took from her time as a Rattler came from her All-American years on the track under the late Bobby Lang. Every time she went out to run the 400, “it was never a pleasant experience,” she says. “You always knew the same thing going in, no matter what or how well you did, you knew, ‘I’ma get my ass kicked today.’”

Each day at practice, and every race she knew there was a hard lesson waiting for her at the finish line. The only thing that got her up in those sticky Florida mornings was her passion for her craft. Her sheer love for the game. There’s a quiet self-confidence in 400-meter runners in the track world. They think they are the secret stars of the show. The 4x400 relays Miss Pam excelled running anchor on was the last event of the meet.

Naturally, she considered herself nothing short of a showstopper.

“It’s the last event. People stayed to make sure they saw us run. And, then, you step onto the track, knowing it’s gonna hurt, but that pride would swell in you and you would never want to be the weak link,” she says. “So, you do learn. Even to this day, I don’t want to be the third wheel. Even though, as a sideline reporter, it’s just the natural pecking order.

“But,” she offers. “That’s if you treat it that way. I don’t go into a game thinking I’m third at anything. … I don’t see the finish line yet, as far as this is concerned,” she says of her career with a breath of energy.

“I’m a lifer … people just look at you,” and she rolls her eyes again, mimicking the endless questions she gets. “I get that retirement question all the time,” Miss Pam says. And for the first time since I’ve met her, I see a transparent frustration take over her disposition. It felt like any moment the production room was about to be engulfed in lava.

“It makes me f— crazy,” she says.

Doesn’t it mean something when someone you love falls in love with what you do? When those we’ve deemed as blessed are proud of what you’ve given back to the world? When you can leave an indelible legacy behind for your loved ones? Part of that ideology has given Miss Pam wings over the years. When Mary went, and then John even more recently, it took something from her. Once Jacque, one of her two sisters, went a few years ago after John, it was almost like Miss Pam couldn’t move. Tragedy robbed her of her spirit, grief stripped her of that unique drive. The way she saw it, all she had left in some ways was the game. Often it is in the midst of woe that our art is able to harness an arcane courage. All she could do was keep her routine, keep her head up and head out to another stadium.

She’s only missed a handful of games in 30 years at Fox, and her family, or her health, were often the drivers. It was usually when she felt like she’d be a detriment to the broadcast, rather than worrying about her own health. Every week for the last decade, her migraines have increased. I’m sure it didn’t help that she was slugged with a tight spiral from a backup quarterback 11 years ago during a preseason game. The incident left her concussed, needing to stay in a lightless room for five days and only worsened the chronic migraines she has battled as an adult. She’s had fibroid surgeries almost every two years, like clockwork. There have been game days when she’s had to tell her driver to pull over so she could vomit in the road, the pain being too unbearable.

But, every week, difficulties or not: there’s Pam Oliver on our television screens, trudging through it all, for less than 30 seconds at a time. So, as the calls for her retirement have come more frequently — even to the point where members of her crews ask her when she’s hanging it up — she remains unbothered by the demands that she be done.

“When I dreamed of this job, I didn’t say: ‘Then when I get to this decade of my life, it’s over,’” she says. “For women, it’s pushed in front of you a lot more than it is for men.” For a moment, the heat continues to rise. “If I’m the longest tenured sideline reporter ever, with well over 500 games,” she huffs. “Why would you walk away from the best job, in the world, that you absolutely love? Come Sunday, kick off? Trust me. Sunday at one o’clock or four o’clock, it still excites me. And I get on that plane at night, dead tired, thinking, ‘You just worked a football game.’”

The temperature lowers for a second, and I see her eyes glow between her sentences.

“And what are people talking about?” she asked me. “The game. And I was there.” She sounds like that little girl who dreamed of being Carole or Iola, captivated by the chance to tell the news. “It was never for me to be front and center,” she says. “Just being at the event was friggin’ cool.”

So, the idea she’d give all of that up? It pisses her off to even consider it.

“It frustrates me because the question is rude,” she says. “Retirement is not in my vocabulary as far as journalism is concerned. People think because you’re on television you’re holding on for dear life to be on television. That’s just where my job happens to be. That’s just where the sweetness is. It’s not that I’m holding on,” she cups her hand over her mouth and begins to whisper. “I’m not trying to be on TV for the rest of my life,” she laughs.

“I realize I’ve already surpassed what a lot of people have done for this long. Some people question my ambition, but,” and now she grows secretive. “You all don’t know what else I’m doing,” the smile is returning. “Very few people do.”

There’s persisted an assumption about Miss Pam for the last decade that she’s merely holding on for dear life at Fox. There were moments, as she’s described plenty of times, that felt like setbacks of no return for her career after being cast aside for the younger, whiter talents Fox has transparently tried to groom instead. The change by Fox that took her off the “A” team for the football broadcaster came with torrents of questions. Plenty she still chooses to ignore. “I do appreciate some privacy,” she says. She wants there to remain parts of her life the public can’t grasp. And would you blame her after the way she’s been treated?

The underdog player with Tongan roots, Tuli Tuipulotu, became a USC star and a rookie standout with the Chargers never forgetting where he came from.

“I’ve been doing this for well over 30 years, so I understand the business and realize there’s only so much you can control now,” she says. But, “that’s something I still struggle with at my age,” she admits. “Not everything is under your control.” Alvin has taken it upon himself to try and be the filter between their house and the nastiness that’s spread about Miss Pam online. “If there’s some wise-ass article, if there’s something critical about my hair or makeup or what I wore, he doesn’t tell me.” Of course she cares, but gone are the years when this could keep consuming her. “I don’t have the time or energy to devote to everyone’s opinion about every, single thing. It’s just not my personality. If I sat around and worried about what everybody said or did, or this article or that article, how do you get out of bed? How do you wake up?”

But, this woman was never raised to be a quitter. So, she refused to see this as a demotion. She was still doing a job she fought to get to, and wasn’t the type to mope while still employed.

Miss Pam had to cover agriculture when she started her career. At one point she dreamed of just making it to a market in South Carolina because she couldn’t take Huntsville or Buffalo any longer. When she finally felt like she was making decent money doing the news, she still hungered to get into sports. At the only moment she had a chance, one of her news directors, Bob Franklin, told her something she seared into her memory: “It’ll be the biggest step down you could ever make,” he said. “No one’s ever going to hear from you again. Your name won’t matter.”

When she finally got her crack at sports coverage, she signed up to work on the weekends. She covered marathons no one wanted to be bothered with. When she was a sprinter in college, she engineered opportunities for herself to freelance stories for the Orlando Sentinel.

She was always doing more than what she could carry trying to remind herself that it wasn’t a fluke she was here.

The art of survival in the world of the press can be a tricky one. Japanese novelist Kazuo Ishiguro once told The Paris Review that idealistic people become misanthropes when they’re let down two or three times. But, we mustn’t get disillusioned when we ultimately get knocked back. “All you’ve discovered is that the search is difficult,” he explained. “And you still have a duty to keep on searching.” For Black talents of any generation, the threat of constant misunderstanding or burnout can swallow most of us whole. Broadcasters, particularly those without the privilege of whiteness, have often told me that it requires an arduous process — sometimes taking their whole careers — to authentically sound like themselves while hurdling the barbed wire of the industry. And somehow, if success or longevity is the test you’re willing to pass, endurance is a sport all of us have had to become proficient at. Miss Pam seems to have pledged to herself that she won’t rest until her body is worn, or until she’s given every last ounce of energy she has left to the game.

“Why isn’t this good enough?” she asks me. “This is the best job going. There’s this assumption that even after doing this, for almost 30 years, at one place, surely, it has to be old, or I have to be bored or I’m just going through the motions.

“If people saw how I worked,” she says. “They wouldn’t go there.”

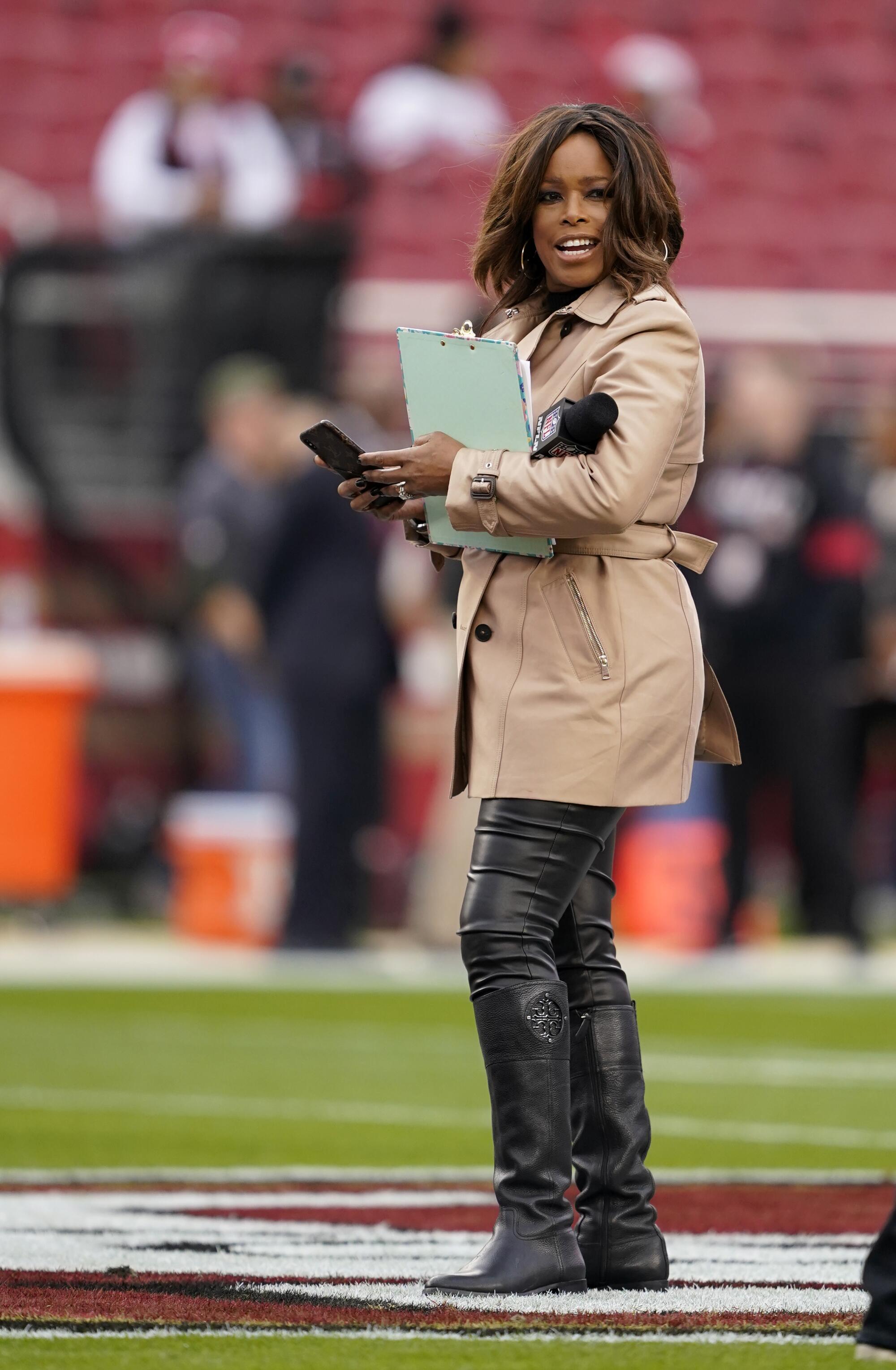

The next morning, two from Hallow’s Eve, Miss Pam arrives at a back gate at Lumen Field, strutting down a byway between two 20-yard television trucks. She made the gray parking deck bloom with color. She wore a rust vest and matching jacket with the collar popped to the sky. I couldn’t tell if that was the soul of the sideline or Clark Kent. Her hair was laid to her shoulders, nearly touching the vintage Van Cleef purse she freed from storage.

She offers me a hug layered with luxurious perfume. “There’s nothing like NFL Sunday,” she beams. I’m sure there isn’t if you carried it like Miss Pam does. Down the back hallways of the Seattle stadium, walking like a woman on a mission, ignoring the security guards and old heads gawking right out of her line of sight. “Pam Oliver?!” one brotha said, trying not to yell. “Wow,” a few yards once she was out of earshot, he could be heard, now slightly yelling, “Meeting her would be a dream.”

Anyone else would crack at least a grin. Yet, her eyes were straightforward. Miss Pam’s focus was on nothing besides football. She takes her role as a responsibility, something that doesn’t come lightly.

“From where I stand, knowing how fleeting this can all be, I’m almost like a Mama Hen,” she tells me. “I want young players to know and understand that there is a way to go about being a pro. So, I impart wisdom even though they haven’t asked me.” See, y’all. I ain’t the only one calling her “Miss Pam.” Plenty of players that Seattle morning did the same. Most of these jokers she interviews on the field, whether they shoot her straight, or give her the runaround, appreciate the inherent warmness she’s shown over the years. There’s a known care when she asks you a question.

“I’m always kind of volunteering little tidbits about how to succeed,” she says. “Getting to know these young men in this sport is hard to get in, and easy to get out, it’s hard to be a player in the National Football League.” She sees herself needing to protect the next generation of players. “You can’t take this stuff with you,” she says. “Why wouldn’t I share it?”

Watching her work on game days is, frankly, exhausting. In the hours before kickoff, she’s running sideline to sideline, shaking hands like a senator while hunting for stories for the broadcast. She operates like a soldier from a foxhole, constantly ducking and diving between linemen and backers warming up. If you’re stretching, she’ll step over you. If you’re in her way, she’ll walk right past you. She’s vigorous in the pursuit of her goals. And, if she was planning to be done sometime soon, she certainly doesn’t move like she’s on the verge of slowing down.

“If you’re watching the game,” she says from the sideline. “You’re not contributing.” She motioned an index finger and spun it rapidly in a loop. “Once the game starts, I’m running all around the stadium. I’m like a chicken with my head cut off,” she laughs.

After kickoff of Seattle versus Cleveland, in the first quarter alone, I watched Miss Pam zigzag sidelines, going between Seahawks and Browns, no less than two dozen times. She was insistent on always keeping her nose on the ball. She is almost always scribbling, at least when she’s not speed walking, her head tucked into a yellow legal pad. She only looks up to see game action, and continues her endless, four quarter cycle of jotting, looking, reporting and running around the loop of Lumen Field.

Alabama pushed Michigan to the limit, but the mighty Crimson Tide’s overtime loss proved the program is no longer invincible in playoff crunch time.

When this football season ends, Miss Pam will have been at Fox for three long decades. Her biggest annoyances, aside from her being the talk of the town no matter what she does or how she does it, and the constant thought that she will have to give up that microphone one day, are rather pedestrian. I’m sure she’d love a little less wind in her face during her live hits. It’s really messing up the stately aesthetic she’s curated for herself. But, otherwise, she can’t see herself stoppin’ no time soon. She’s even joked that you’ll have to drag her from the field. Feet first.

Even now, tending to her spots on the sidelines, I can see the pieces of the game that Miss Pam sought when she was a girl, when the common denominators of her life only amounted to sports or journalism. They are two anchoring points she’s unwilling to leave behind her. The part of her that is still unwilling to do wrong by football or her viewers. After all: she swiped something from all those mornings with Madden and Summerall when she watched those games with her mother, father and two sisters — joined at the hips in their Dallas living room. By the time she was the duo’s colleague, sequestered to the side of the room and only beckoned for when asked at the start of their relationship, she was still there studying, trying to find the best nuggets from players or their families that she could earnestly share with America each Sunday afternoon. In a way, Miss Pam is still out there hustlin’ for us, the viewer. In another, she’s still out there, fightin’ in the trenches just as much as the guys, for her own ambition: to maintain the best seat in the house each week, to embolden her happiness and to bring the news to the next Pam Oliver waiting patiently for her broadcast, from a living room somewhere unseen.

“I look at it now and I actually feel sorry for a lot of these young journalists,” she tells me. “Because now, it’s almost about being a celebrity more than just being a journalist. You got to play the game, too. And growing up in news, your job was to be in the background. You were there to tell stories, not to be the story or out in front, or write about every single element of your day and life. That was frowned upon.” She closes her eyes and sighs. “There’s a sameness, I think, in a lot of who’s on the air. There’s a lot of sameness. And it gets boring.

“See,” she says, the life shining in her eyes. “When somebody shows up that’s a little bit different, with some flair?” she says, extending those vowels again, almost as if she could be speaking of herself. “I perk up,” she says. “I sit up a little straighter.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.