How the Philadelphia Eagles nearly became the Phoenix Eagles in 1984

- Share via

PHOENIX — The Philadelphia Eagles are heading to Phoenix and their fans are thanking the heavens.

Thirty-nine years ago, the Eagles were heading to Phoenix and their fans were cursing their fate.

In a dark moment in Philadelphia sports history forgotten by many, there was a brief stretch at the end of the 1984 season when the beloved Eagles almost relocated to Arizona, site of Super Bowl LVII.

It came on the heels of the Raiders moving from Oakland to Los Angeles and the Colts leaving Baltimore for Indianapolis, so the concept of an established franchise uprooting was entirely plausible.

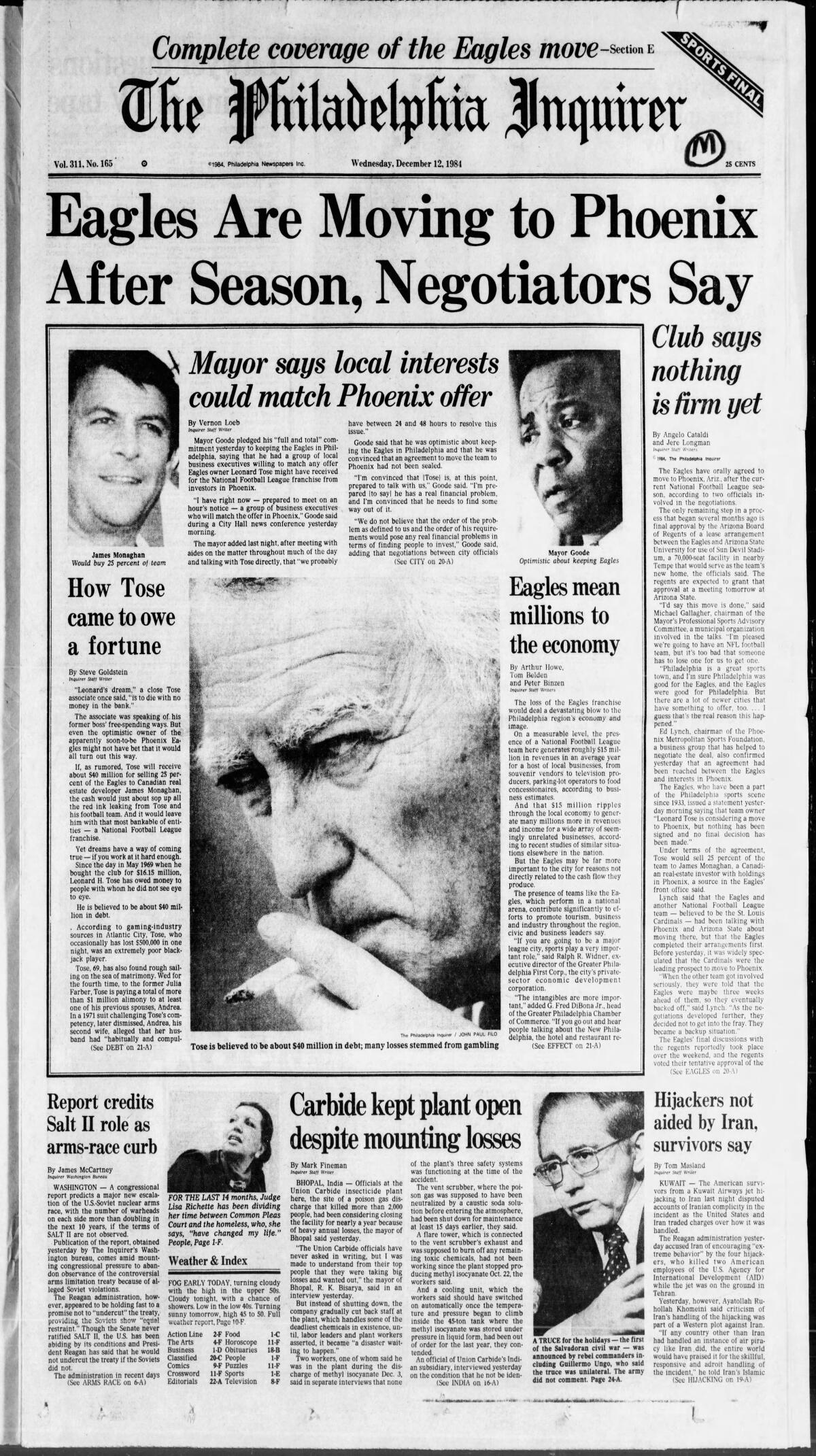

“The idea of the Eagles picking up and moving just turned the city upside down,” recalled legendary Philadelphia sports columnist Ray Didinger, who learned the news in the middle of the night that cash-strapped owner Leonard Tose had agreed to sell nearly half of his team to get out of debt. The caveat was he’d have to move the team to Phoenix.

Andy Reid has emerged victorious the last six times the Eagles and Chiefs have squared off. Will he prevail again in Super Bowl LVII?

“The story broke in Phoenix,” Didinger said. “I was sound asleep at 1 o’clock in the morning and my phone rang. I picked up the phone and it was the night sports editor and he said, ‘Have you heard anything about the Eagles moving to Phoenix?’ And it was like, ‘Did I just dream this? What are you talking about?’ ”

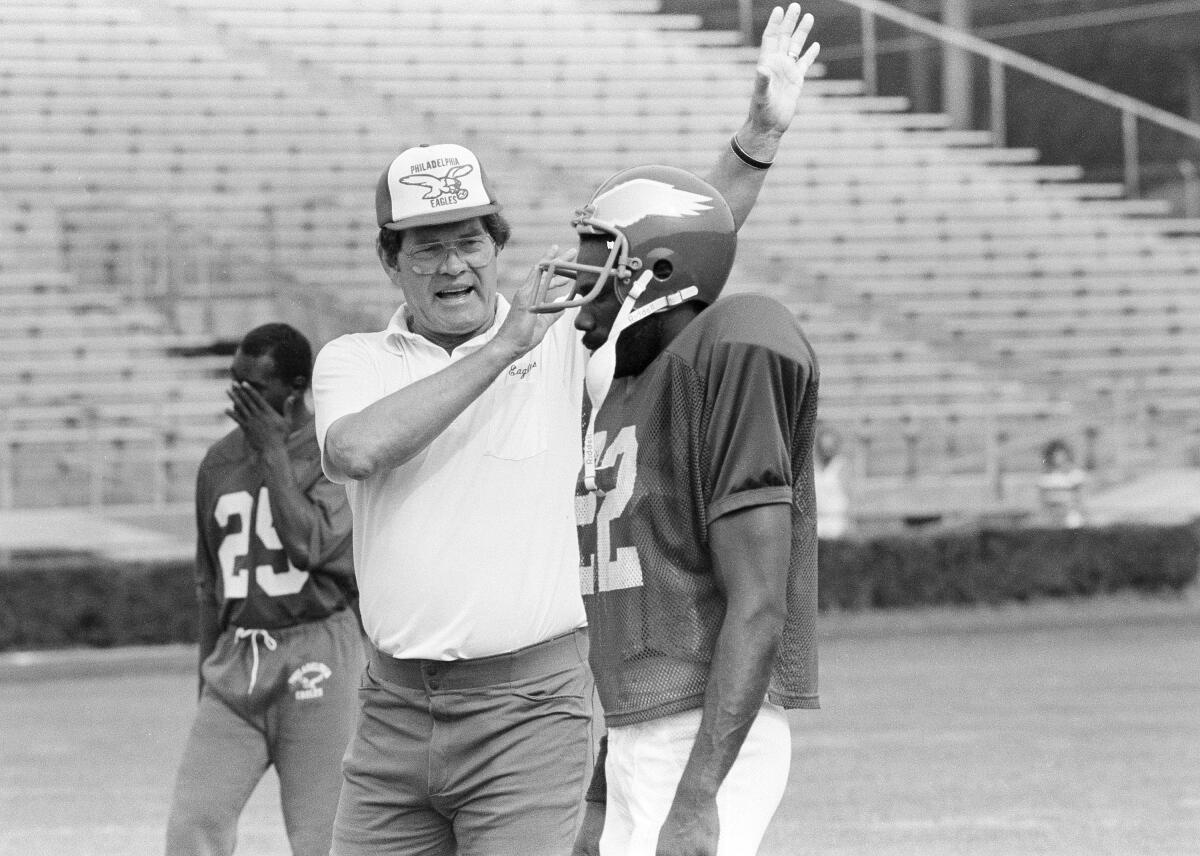

The story out of Arizona said the deal was done. There were two weeks left in the regular season, the Eagles were bumping along with Marion Campbell as coach, and they would be packed and gone by the end of the year.

The basics of the story were that Tose would sell 25% of the team for $40 million to James Monahan, a Canadian real estate developer, with the promise to move the club to Arizona. That would allow Tose to get out of debt while retaining controlling ownership of the Eagles.

Tose’s daughter, Susan Fletcher, was negotiating the deal and only the final details had yet to be worked out. The official announcement was to come Dec. 17, 1984, a day after Philadelphia’s final game in Atlanta.

Of course, Didinger reasoned, the story could be a hoax or simply bad information. He asked his editor who wrote it. It was longtime Arizona Republic sports columnist Bob Hurt.

“Right away I said, ‘Well, then it’s legit,’ ” Didinger said. “Bob Hurt was one of those guys who had been in Phoenix forever. He was the sports columnist but way more than that. He knew all the sports people in town, he knew all the politicians in town. He knew everybody and everybody talked to him.”

Thus began a two-week nightmare for Philadelphia, with the city doing everything it could to hang on to a football team synonymous with the city. The Eagles were founded in 1933 when a syndicate led by Bert Bell and Lud Wray bought the former Frankford Yellow Jackets for $2,500.

“It’s a great sports town, and the Phillies, Sixers and Flyers certainly have a lot of fans, but the Eagles are the No. 1 attraction in the city,” said Hall of Fame radio announcer Merrill Reese, voice of the Eagles since 1977. “Philadelphia is, first and foremost, an Eagles city.”

Tose was an eccentric and colorful team owner, and although prone to money problems was regarded warmly in many ways.

“He was bigger than life,” Reese said. “He was extremely generous and loved the team, was so proud of his team and dressed to the nines every day. He would fly from training camp back to the complex in a helicopter. He had a yellow Rolls Royce at one point.

“He was the kind of guy who would find a story in the newspaper about some poor soul someplace in trouble, or a child with a medical need, and anonymously donate a large amount of money to that family. He was kind of like the television series, ‘The Millionaire.’ ”

Yet there was a downside. In 1999, four years before he died, Tose told a congressional hearing on compulsive gambling that he lost between $40 million and $50 million on betting. After his home in Philadelphia was confiscated for unpaid taxes, he lived his final years alone in a downtown hotel room.

Norman Braman bought the Eagles in 1985 and owned them until 1994, when current owner Jeffrey Lurie took over.

Monahan, who died in 2020, was quite a character, too, and had a wide array of real estate holdings. When news broke of Monahan’s intentions to buy a piece of the Eagles, Philadelphia reporter Maria Gallagher tracked him down at Circus World, an amusement park he owned in Florida.

Monahan agreed to the interview … but only if Gallagher would first ride the roller coaster at the park.

“I’m not a big fan of roller coasters,” said Gallagher, who is married to Didinger. “He made me sit in the front car with him. The photographer actually took a picture of us and I look like I’m about to die. But true to his word, I rode the roller coaster with him and he gave me an interview.”

There was no glee in Philadelphia at the prospect of the Eagles leaving. For two weeks, it was the biggest story in the NFL.

“There was the disbelief stage, then the panic stage, then the anger stage,” Didinger said. “Philadelphia went through all three stages in like the first day. It was, ‘I don’t believe it. I can’t believe it. Oh my God, I’m going to punch somebody.’ That’s how it progressed.”

When the Eagles played that otherwise meaningless finale in Atlanta, hundreds if not thousands of Philadelphia fans made the trip. The Eagles won that game and finished the season 6-9-1.

“They really believed this was going to be the last game of the Philadelphia Eagles,” Didinger said. “They had signs and stuff, just in tears at the thought that this might be it.”

Philadelphia and the NFL threw up as many roadblocks as it could, and ultimately persuaded Tose to abandon his scheme. It came at a cost. The city, which owned the stadium, had to make financial concessions that included building luxury boxes at the rim of the venue.

Still unknown is whether Tose was bluffing about the Phoenix move to extract a better deal from Philadelphia and the NFL. Regardless, the scare was very real.

As for Hurt’s role, he sounded the alarms early with his Eagles-to-Phoenix story, angering some people in Arizona and ultimately becoming a heroic figure to Eagles fans in Philadelphia.

“Bob Hurt saved the Philadelphia Eagles,” Didinger said.

Travis and Jason Kelce are on opposing sides for the Chiefs and Eagles in the 2023 Super Bowl, and their father understands their competitive nature.

One Philadelphia writer suggested the city should erect a statue of Hurt outside Veterans Stadium. Hurt, who died in 2009, joked that he preferred to be near the “Rocky” statue by the city’s Museum of Art.

“Bob Hurt seemed to know everyone, and for whatever reason, maybe it was his Oklahoma drawl and friendliness, they liked him and told him stuff,” said Kent Somers, longtime sportswriter for the Arizona Republic.

“He would love the irony that 39 years after his column stopped the Eagles from moving to Arizona, the Eagles are in town playing in the Super Bowl. And that people are writing about him.”

Some people in Philadelphia will never forget the time when Eagles fans were ready to dip their Tose in the water.

By his ankles.

Watching their sons play against one another in the NFL can be an ‘emotional teeter-totter’ for parents who want their children to win.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.