Column: ‘That was absolutely deliberate.’ Focus at Jackie Robinson Museum is off the field

- Share via

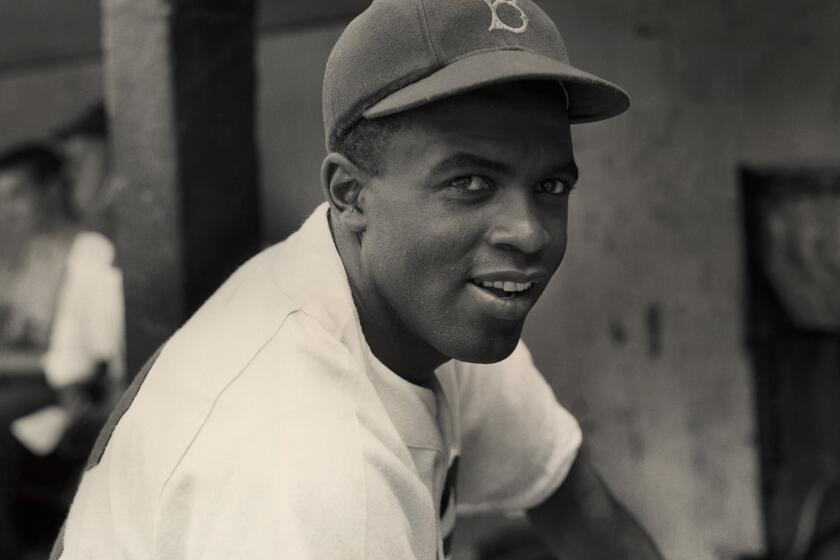

NEW YORK — There was a time, and not so long ago, when you could ask a major league player about Jackie Robinson and get a shrug in return. The league retired his number in 1997, on the 50th anniversary of his debut, with President Clinton in attendance. That made for a nice ceremony, but it was not until 2007 that Jackie Robinson Day really took hold.

That is when Ken Griffey Jr. called Bud Selig, then the commissioner of Major League Baseball. To this day, Selig remains astounded by what Griffey told him.

“‘A lot of the guys’ — and I’m quoting him directly — ‘don’t know who Jackie Robinson is,’ ” Selig told me the other day.

Griffey asked whether he could wear the retired No. 42 on Jackie Robinson Day. Within two years, every player did, and the annual remembrance serves a dual purpose: a regular checkpoint in baseball’s quest to regain prominence in the Black community, and a celebration of Robinson breaking the color barrier.

“I believe it is the most important and powerful moment in baseball history,” Selig said.

That is what makes the opening of the Jackie Robinson Museum so important. By this 75th anniversary of his debut, MLB has done a commendable job of reclaiming and sharing Robinson’s legacy as a baseball player.

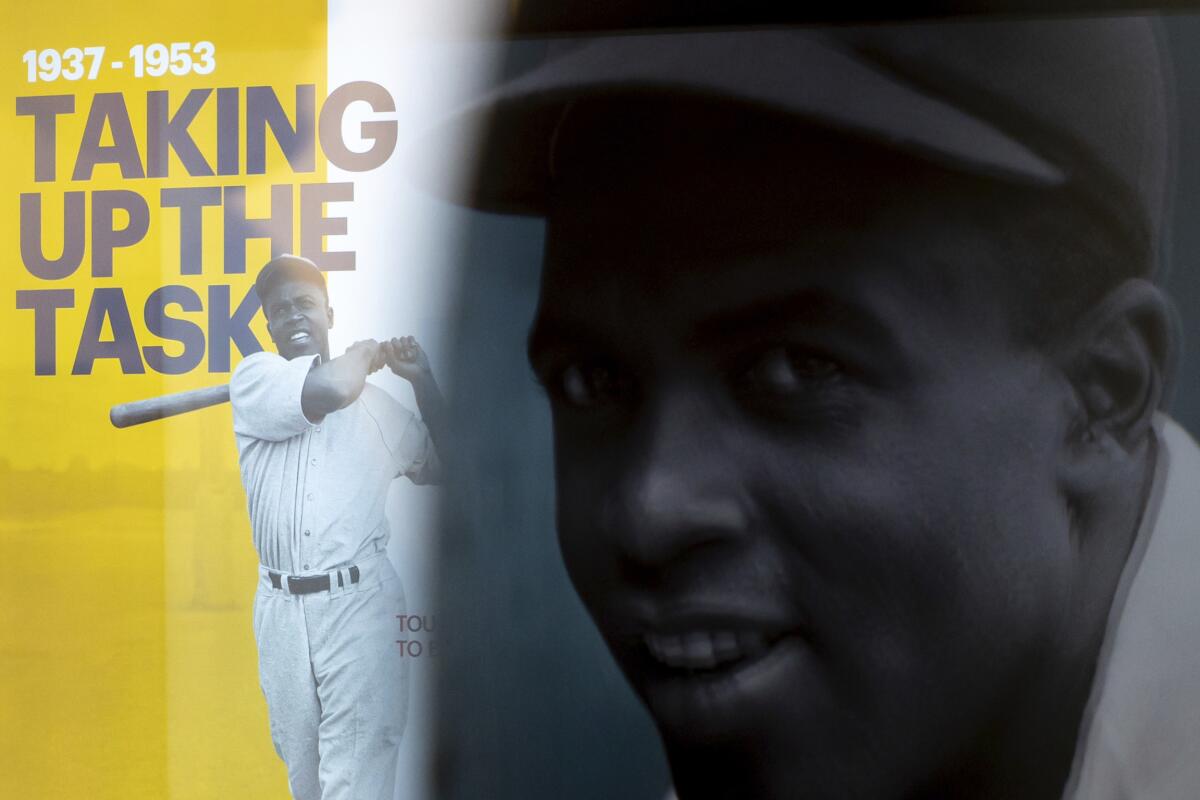

The museum also tells the story of Robinson’s amazing life off the field. Walk into the museum, and the first room you see is not one that celebrates his athletic accomplishments.

“That was absolutely deliberate,” said Della Britton, president and chief executive of the Jackie Robinson Foundation.

“Even if you come in with the idea to see the baseball story and learn more about that, you have to walk through that room that talks about his commitment to economic opportunity and civil rights and social justice.”

Robinson’s life tasks are displayed in large capital letters in that room: SOLDIER, CAMPAIGNER, PUBLIC SERVANT, ACTIVIST, FUNDRAISER, ORGANIZER, PROTESTOR, ENTREPRENEUR, CITIZEN and more.

There are the “by the numbers” displays you might expect in a museum about a sports star, but “3” is the number of presidential candidates for which he campaigned, “4” is the number of presidents with whom he corresponded about racial injustice, “6” is the number of years his department store was open in Harlem, and “1949” is the year he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

MLB celebrates Jackie Robinson Day on Friday, which is the 75th anniversary of the Dodgers legend breaking baseball’s color barrier. Here’s our coverage.

Of all the artifacts on display, Britton said she is perhaps most proud of sharing Robinson’s testimony before that committee, with his handwritten notes alongside his typewritten speech.

The white media, she said, played up the perceived feud between Robinson and Paul Robeson, a prominent Black actor and singer who allegedly had said Black Americans should not go to war against the Soviet Union when the communists there had treated Blacks with dignity. Robinson called the alleged comments “silly.”

But the museum also displays coverage of the testimony in the Black media, which focused instead on Robinson’s core message: “The fact that it is a Communist who denounces injustice in the courts, police brutality, and lynching when it happens doesn’t change the truth of his charges. … Negroes were stirred up long before there was a Communist Party, and they’ll stay stirred up long after the party has disappeared unless Jim Crow has disappeared by then, as well.”

To the congressman who that day told Robinson to be patient, Robinson asked whether Blacks had not been patient long enough. To that point, the museum highlights a 1950 letter to Robinson from Branch Rickey, the Dodgers executive so celebrated for signing him.

Robinson had expressed interest in managing. “I hope the day will come soon when it will be entirely possible, as it is entirely right, that you can be considered,” Rickey wrote. In 1972, Robinson died, without ever seeing a Black man manage in the major leagues.

The museum opens to the public Monday. Robinson’s team got a private tour last Wednesday, before the Dodgers played the New York Mets.

“Jackie’s passion was civil rights and equality, and more so than baseball,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said. “It was more of baseball was just a vehicle for him to use his voice, which is pretty cool to see and actually pretty inspiring.”

That is the ultimate mission of the museum — not simply to share how Robinson made a difference, but also to encourage that you do the same.

In one area of the museum, visitors can select one of Robinson’s causes — fair housing, equal pay, police brutality, school integration, job creation or drug policy advocacy — and learn what he did to advance the cause and what someone might do to advance the same cause today. Robinson, for instance, helped launch Freedom National Bank, which offered jobs, loans and mortgages to the Harlem community.

In another area, visitors can see and hear testimony from distinguished Americans on how Robinson affected their lives — from some athletes, yes, but also from the likes of former President George W. Bush and former Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr.

Before the Dodgers defeated the Kansas City Royals for their 12th consecutive win, they made a special visit to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

The museum is highly interactive, with your visit determined by your interests. That made for a delightful morning for my 12-year-old daughter Aria, who is not much of a baseball fan and told me she considers most museums as places to “walk around and look at stuff while your parents gasp and point at things.”

In this museum, she said, “I learned a lot more than I thought I would without even realizing, because it was so fun.”

If your interests are limited to baseball, there is plenty to enjoy here, including a scale model of Ebbets Field, with storied Brooklyn broadcaster Red Barber calling the action. (Britton said Vin Scully, who told a classic story about ice skating with Robinson, is cited in the museum too.)

But the museum fairly stands as an inspirational and respectful tribute to a man whose Dodger Stadium statue features this Robinson quote: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

Times staff writer Jack Harris contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.