- Share via

The bases were loaded with two outs in the ninth inning when Nelson Figueroa, pitching coach for the Staten Island FerryHawks, waved to the bullpen for a reliever. A right-hander answered with a nod, jogged to the mound and four pitches later was out of the jam, getting the batter to pop out.

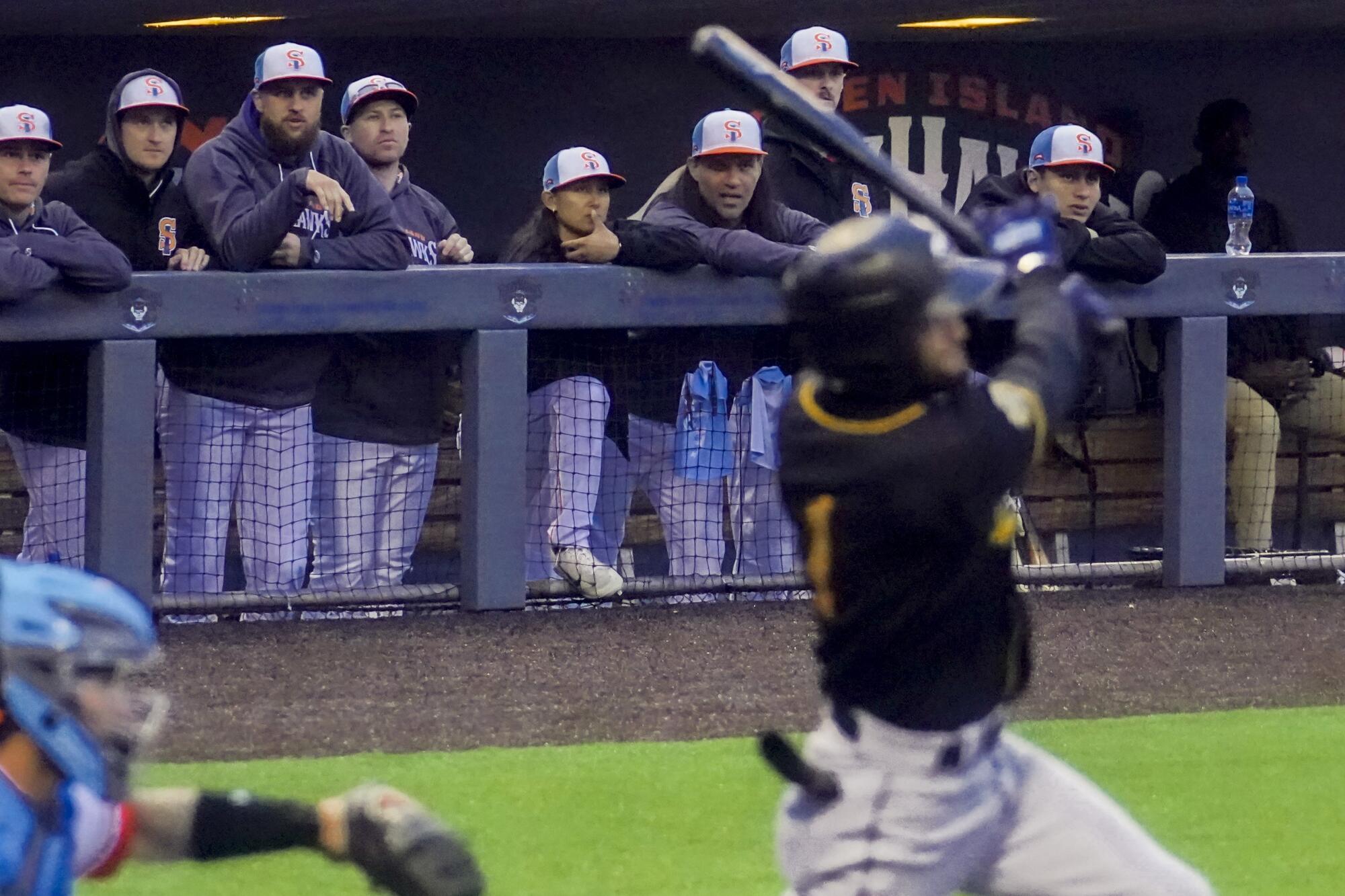

Similar scenarios play out in professional ballparks across the country every night. This at-bat, before a crowd of 735 on the banks of New York Bay last month, was historic because it made Kelsie Whitmore the first woman to pitch in the Atlantic League — a 10-team independent professional league on par with the highest level of minor league baseball.

Three days earlier Whitmore, a ponytail covering the blue No. 3 on the back of her uniform, had become the first woman to start in an Atlantic League game, playing left field and reaching base once in three plate appearances.

Taken together, the two milestones raise an interesting question: If a woman can pitch and play the outfield in the country’s top-ranked independent league, will we soon see one in the major leagues?

“Yeah, I think it’s a definite possibility,” said Mike Scioscia, who spent 32 years in the majors as a manager and All-Star catcher with the Angels and Dodgers. “I don’t think it’s a far stretch to see some girls be able to develop and pitch.”

“I think it’s highly improbable,” countered Tom House, a former big-league reliever who has gone on to become an expert on pitching mechanics. “It would have to be a unique set of circumstances for a female to get on a roster on a major league level.”

Ila Borders, who arguably came closest when she pitched three seasons in the independent Northern League, says they’re both right: It’s possible, if improbable, for a woman to reach the top level of professional baseball right now. The fact the question is no longer being met with disdain is progress.

“The biggest thing in my mind is they’re trying,” said Borders, who had a 2-4 record with a 6.60 ERA in 47 games from 1997 to 1999. “When I was playing it was an uphill battle. They were trying to do everything to not let me play.

“The tide has turned,” said Borders, who in 1994 became the first female pitcher to start a college game when she pitched Southern California College — now Vanguard University — to a 12-1 win over Claremont-Mudd-Scripps.

While Borders went it alone, Whitmore is part of a movement. In January, 17-year-old Genevieve Beacom, a 6-foot-1 left-hander, became the first woman to pitch in the Australian Baseball League, throwing a hitless inning in her debut. Last month Anaheim High’s Jillian Albayati became the first girl to start a CIF Southern Section championship game on the mound — she also drove in her team’s only run — and 20 girls have played in the Little League World Series.

That’s drawn the attention of people at the highest levels of the sport.

Five years ago, MLB started the Trailblazer Series, an instructional and introductory initiative for young female players. With the help of USA Baseball, it recently expanded that outreach through three other programs designed to identify and groom female players in the states, as well as in Puerto Rico and Canada. In addition the commissioner’s office has added girls’ leagues to its Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities project.

This season, the San Francisco Giants’ Alyssa Nakken became the first woman to coach on the field during a major league game.

“Women playing baseball is an important part of our sport’s history. That legacy is also significant to the game’s present and future,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said. “We are committed to ensuring that any young woman who chooses to play baseball … will have the opportunity to do so.”

The role women play in many other top-tier men’s professional sports has increased in recent years: Becky Hammon was an assistant coach for the San Antonio Spurs of the NBA, a league that has six female referees. The NFL had a record 12 women assistant coaches last season and recently promoted its third female official. This fall, six women will officiate soccer’s World Cup for the first time.

Major League Baseball has struggled to keep up, although Rachel Balkovec did debut this year as the first woman to manage an MLB affiliate — the minor league Tampa Tarpons. Nine other women are serving as minor league coaches and seven are working as scouts.

There has been progress elsewhere: The Miami Marlins’ Kim Ng is the only female general manager in any of the top five men’s professional sports leagues in the U.S. Seven other teams have female assistant GMs.

The idea that a woman could play at the highest levels of the sport isn’t a new one.

Alta Weiss, who pitched in a billowing skirt and was known as the “Girl Wonder,” played for a number of barnstorming semipro teams from 1907 to 1910 before giving up baseball to become a pioneer in medicine as the only female in her graduating class at Starling College in Columbus, Ohio.

Less than a generation later Jackie Mitchell, a 17-year-old side-arming lefty with a devastating sinker, struck out future Hall of Famers Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig on seven pitches while playing for the minor league Chattanooga Lookouts in a 1931 exhibition game. A few days later commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, concerned that Mitchell’s success might inspire other women to play the game, voided her contract, claiming that baseball was “too strenuous” for women.

Landis was proven wrong a dozen years later when Chicago Cubs’ owner Philip K. Wrigley started the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League while many of the top big-league players were fighting in World War II.

Launched partly as a novelty, the league grew to include 10 teams and 600 players, drawing nearly 1 million fans in 1948. It lasted 11 seasons before folding in 1954 and was celebrated in the 1992 film “A League of Their Own.”

In the Negro Leagues, Mamie “Peanut” Johnson won 33 of 41 decisions as a pitcher with the Indianapolis Clowns from 1953 to 1955. The Clowns also had two female infielders, Toni Stone and Connie Morgan.

There’s no record of another woman playing for a top men’s professional team until 1997, when Borders joined the St. Paul Saints. She was followed by Eri Yoshida, a teenage knuckleball pitcher from Japan who played in the Golden Baseball League and North American League.

Relief pitcher seems a likely position for the first woman big-leaguer, especially if she can master a unique pitch such as Yoshida’s knuckleball or Whitmore’s knuckle-change, both of which rely more on technique than strength. With Major League Baseball adopting the universal designated hitter this season, pitchers no longer have to bat, neutralizing the differences in strength and foot speed between men and women. With so many men throwing 100 mph or more, hitters would have to adjust when facing a reliever who threw in the mid-80s but had good control.

“A lot of pitchers that rely on command and movement have a lot of success,” Scioscia said.

“You certainly need a minimum amount of velocity, you need a minimum amount of movement and spin rate on a ball. I don’t think it’s anything that is outside the realm of what you could possibly see in future from a woman.”

House disagrees. After an eight-year major league career in which he won 29 games and saved 33 others for three teams, he earned a PhD in sports psychology and founded the National Pitching Assn., which focuses on a science-based approach.

The science, he says, works against a woman pitching in the majors.

“The issue isn’t that they couldn’t have great mechanics. And they couldn’t be durable, they couldn’t throw strikes. They can do all that,” said House. “But they’re never going to be able to throw with the velocity, no matter what they did.”

House tested that theory with Katie Griffith, a 31-year-old former college softball player who was then coach at Harvard-Westlake High and had a perfect pitcher’s build at 6 feet tall with a long stride.

Although Griffith had thrown underhanded as a softball pitcher, her father had taught her to throw a baseball overhand when she was 8, methodically strengthening her arm by playing catch over long distances. House tried to build on that by using high-speed cameras and wireless sensors to track her mechanics and measure her performance. Griffith adopted a healthier diet, began incorporating foam rolling, icing and sprints up a hill into her workout routine, all in an effort to add velocity to the fastball she needed to complement an above-average curveball.

“But no matter what we did with weight gain, strength-building, mechanics, she could never throw harder than 80 to 83 off the mound,” said House, who worked with Griffith for nearly three years. “It’s just the way women are put together. Unless they cheated with steroids or something, their physiology wouldn’t allow velocity to happen.”

House said the experiment convinced him the path to the majors for a woman may be easier as a position player.

“They’d have a better chance as an everyday player,” he said. “You can’t rule it out. … But it would have to be a unique set of circumstances.”

Whitmore, a switch-hitter who has both pitched and played the outfield against males her entire life, isn’t so sure one path would be easier than the other.

“On the position [player] side of it, there’s more that’s taking place,” said Whitmore, 24. “She’s going to have to play defense and she has to hit. When it comes to the outfield, it’s being able to have good range, have a good arm, being able to throw guys out.”

Whitmore grew up in Temecula, where she played goalkeeper on the girls’ soccer team and baseball on the boys’ team in high school. She also played with the women’s national baseball team, winning medals at the 2014 Women’s World Cup and the 2015 Pan American Games before playing softball at Cal State Fullerton. In 2021 she was named the Big West field player of the year after batting .395 with 12 home runs and an .824 slugging percentage.

Despite that success, baseball remains her passion.

“If you ask any guy that’s playing in this league, that has the goal of playing in the major leagues, my goal is the same thing,” said Whitmore, who throws a sharp-breaking knuckle-change and a fastball that has hit the low 80s. “I grew up playing this game and wanted to pursue it at the next level. I don’t play this game just to do it. … I want to make this game my career.”

The early returns have not been encouraging. In two seasons in the Pacific Assn., a men’s independent league based in Northern California, Whitmore had two hits in 26 at-bats as an outfielder and given up seven hits and seven runs in three innings on the mound. At Staten Island she’s hitless in 12 games and 11 at-bats and has surrendered six hits and 10 runs in three innings as a pitcher.

“It takes some time to develop,” said Borders.

‘You need to produce at this particular level and then you can move up to the next level. That’s really important to have a progression like that so you are showing that you’ve earned that spot.”

Borders also believes the first woman to succeed in professional baseball is going to need certain attributes, not just physical but in behavior and bearing as well.

“It will definitely have to be the correct person because they’re going to have to handle a lot of scrutiny, a lot of pressure,” said Borders, 47, who works as a firefighter in Portland, Ore.

Having come this far, Whitmore prefers to focus on the progress, not the obstacles. Opponents, she said, compliment and encourage her. Fans cheer for her. Rather than voiding her contract, the commissioner of baseball is rooting her on.

“There’s always going to be barriers,” Whitmore said. “With women progressing in the game, people are starting to maybe believe it a little more, but there’s always going to be haters.

“If I have to take the negative comments, if I have to go through the ups and downs being the first one at this level, if it means doing all that but it changes one life and it changes a younger girl down the road, it’s all worth it.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.