- Share via

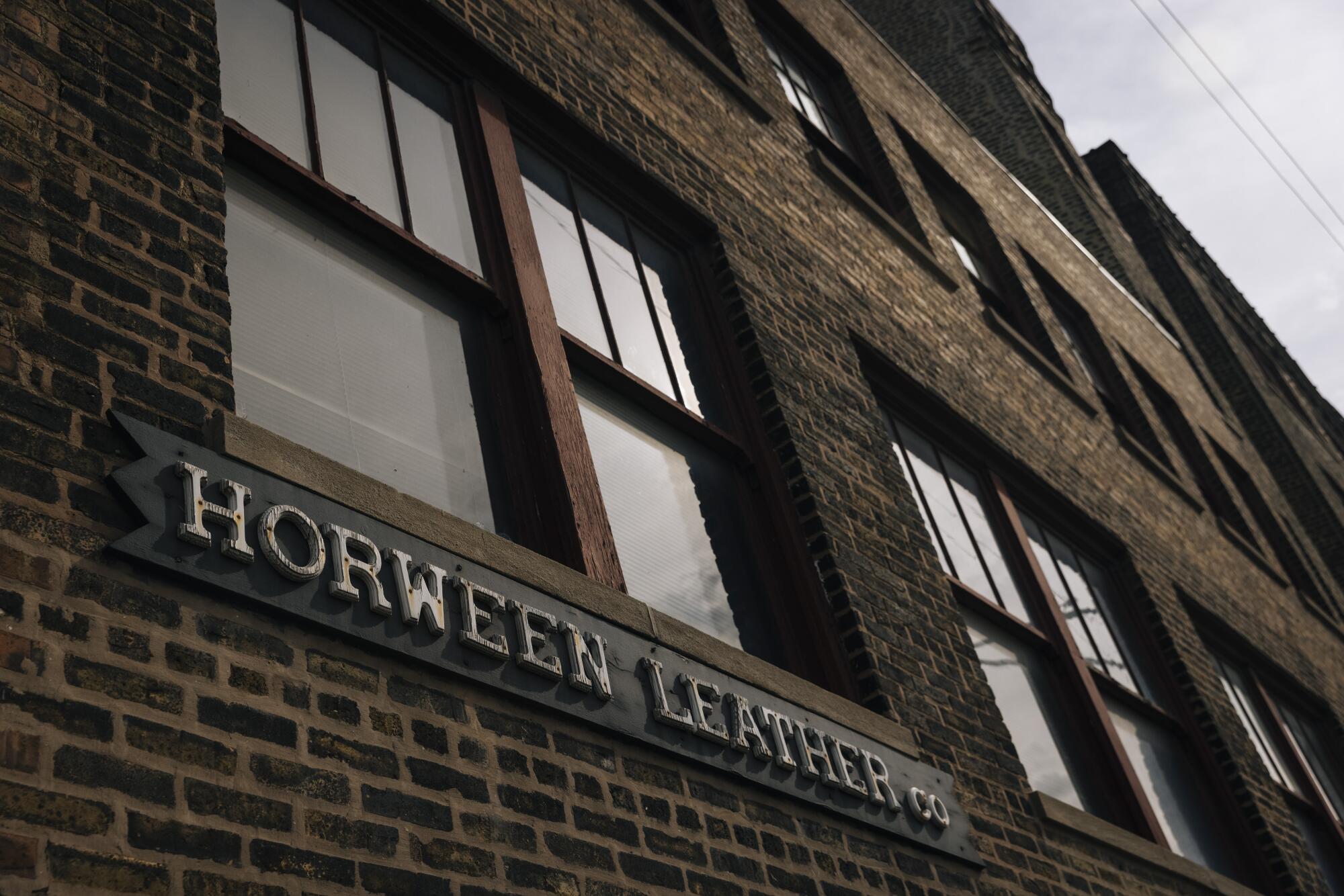

CHICAGO — The noise on the ground floor of the Horween Leather Co. is a deep, constant rumble pierced by the shrieks of blades inside machines that have split leather to within fractions of an inch for more than 120 years.

The smell is so pungent that first-time visitors to Chicago’s last operating tannery are warned that the odor from the oils and other agents that turn hides into store-bound leather products — a dampness from tree bark used when hides are re-tanned; a wooly aroma from unrefined lanolin — might seep into their clothes.

None of it distracted Skip Horween from his search on an October morning.

The 65-year-old first explored this five-story brick building overlooking the Chicago River’s North Branch as a child. In the 1970s, he returned after college to work alongside his grandfather and father as the family’s fourth generation to guide the business. The decades have taught him that certain products are made from specific sections of specific hides; what is good for a Timberland boot is not for an NFL football.

It was why as he looked over his glasses and leaned over a waist-high stack of steer hides, still damp and tinted the blue of a clear fall day here by a preservative bath, Horween raised his voice to be heard upon seeing what he wanted.

In the middle of the former animal’s back, near where the backbone used to press, and where the hide is most dense, Horween found a future NBA basketball.

The ball that is dunked by LeBron James and shot by Stephen Curry during an NBA practice or game are nothing like the rubberized versions bounced on playgrounds, or even those that are standard at the high school, collegiate and international levels, which are made from a synthetic fabric. This is eight panels of leather and, when brand new, slick to handle. It is ready for opening tip only after months of breaking in, as moisture from players’ bodies and dirt from the courts are absorbed into the leather.

“Players will tell you that, ‘The feel of the ball makes me feel like I made it,’” said Kevin Krysiak, the global product and research and development director for Wilson Sporting Goods. “They’ve been dreaming of the NBA their entire lives.”

Every leather ball used in the NBA during the past two decades has begun its life as a hairless hide inspected on Horween’s ground floor, a visual examination that begins a world-traveling journey that takes place almost entirely behind the scenes. Until now. These days, more people than Skip Horween are taking a closer look at the NBA’s central piece of equipment.

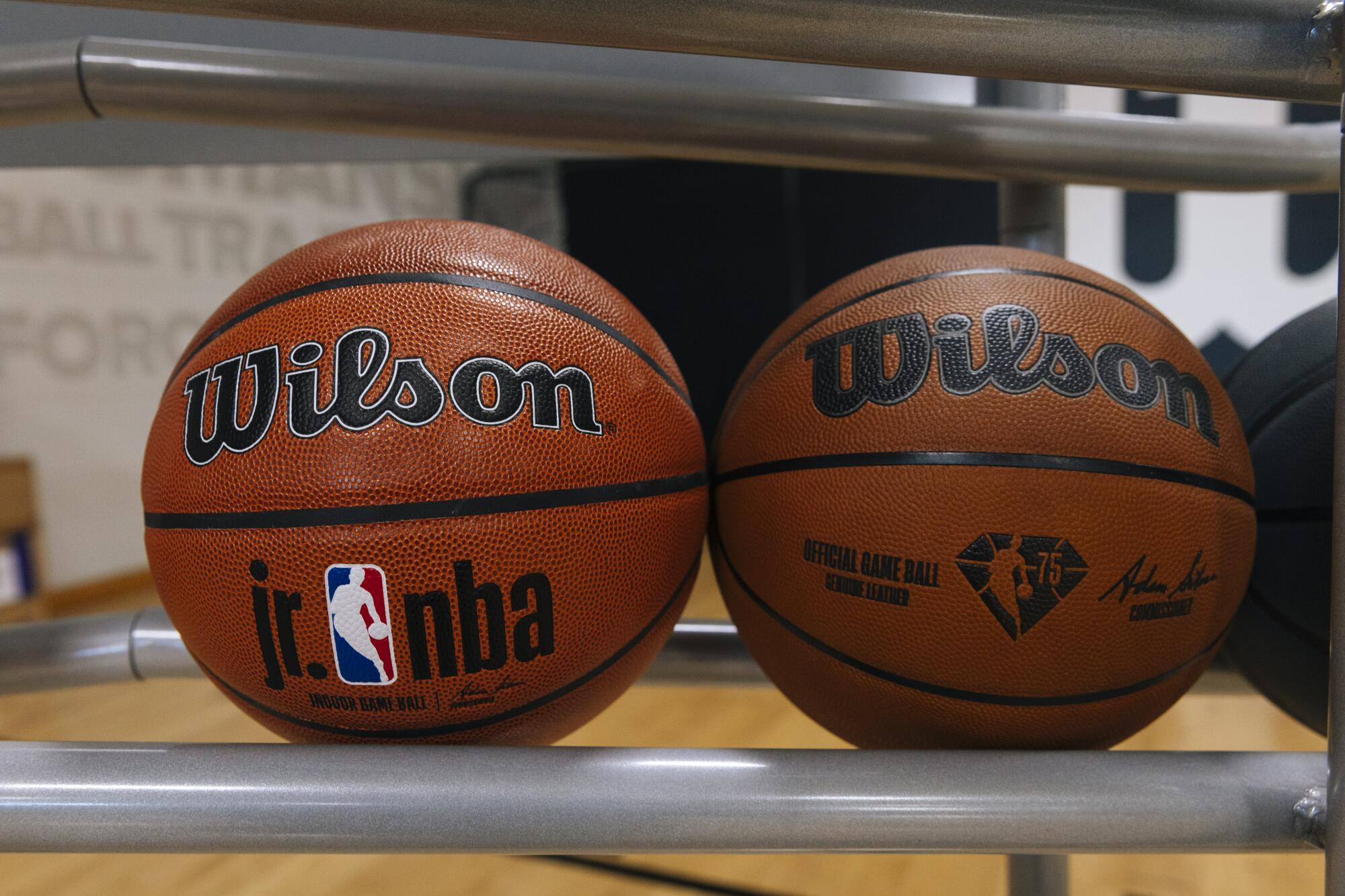

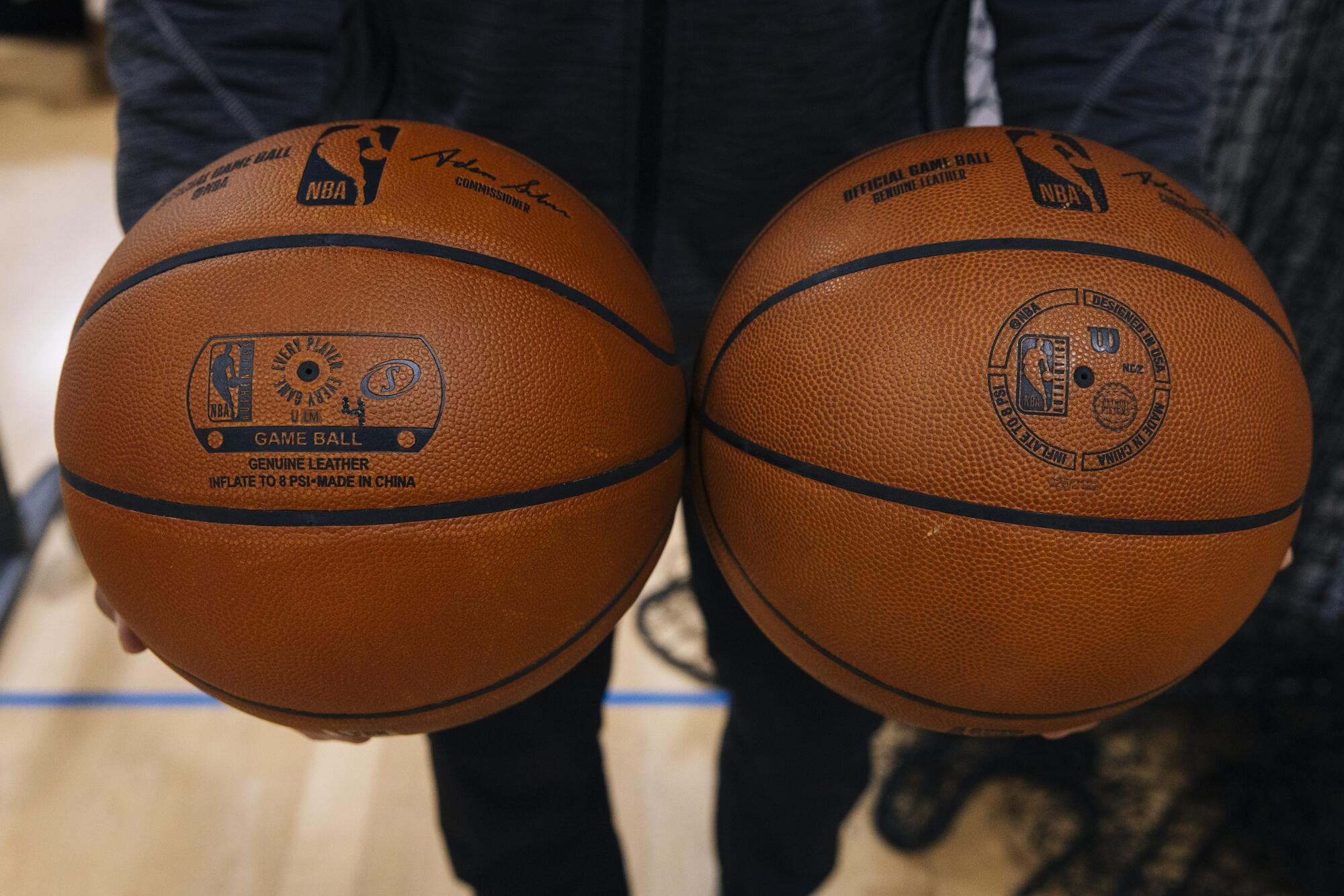

After 37 years using Spalding basketballs, the NBA this season switched to those produced by Chicago-based Wilson, as part of a 10-year deal first announced in May 2020. Wilson balls are also used in the WNBA, the G League, the NBA’s developmental league, and its year-old Basketball Africa League. The visual differences are slight. By NBA rule, the ball must measure between 29½ and 29¾ inches in circumference around the channels, weigh between 20 and 21¼ ounces using between 7½ and 8½ pounds of pressure per square inch of inflation and must bounce between 52 and 56 inches high when dropped from a height of six feet. Just like Spalding, Wilson sources its leather from Horween.

Yet there is another reason the NFL has used the same Wilson-produced footballs since 1941, MLB has stuck with Rawlings baseballs since 1977 and pucks made by Inglasco have skipped across NHL ice since 1986. It’s the same reason the NBA’s last attempt to tweak its game ball, in 2006, ended in a public-relations disaster after furor from its players — any alteration risked raising the ire or undercutting the confidence of players accustomed to one constant.

“As soon as you grab one you know if it’s heavier or it’s more slippery or less slippery,” said Jose Calderon, a Spanish guard who played 14 NBA seasons before joining the players’ union as a special assistant to its executive director. “As soon as you bounce, you feel like if it’s a nice bounce or not, got too much pressure in it or air or if it’s a little bit flat. It’s the way we work. It’s our main tool.”

Even one month into the season, and after more than a year of being directly involved with testing Wilson prototypes, players have not universally lined up in support of the Wilson ball, with some directly attributing the league’s statistical drop in offense to the ball, even as other players, executives and equipment managers have called concerns overblown, citing a range of other factors from the return of fans to arenas, fatigue following a second consecutive short offseason and a change in officiating emphasis that has led to more physical play and fewer fouls.

Ex-Sacramento coach Luke Walton, a player during the NBA’s troubled 2006 tweak, said that this time around, “I don’t see it being other than a name on the ball a distraction for the players.”

In interviews, NBA and Wilson executives expressed confidence in a changeover that relied on feedback from more than 300 players. They also called a certain level of pushback inevitable. It was why, they said, no one during the year-plus transition had looked more closely at the ball than them.

::

Turning a blue-tinted steer hide into a pebbled sheet of leather ready for shipment to a Chinese factory, where Wilson’s basketballs are manufactured, takes about 22 working days at Horween, a process that takes the leather through each of the building’s five floors.

On the bottom floor, hides are tanned a second time, a bit of chemistry with oils and waxes that “bake in” each ball’s grip. On the top floor, a 74-year-old dryer, nearly as large as a gas station car wash, holds 100 hides at a time, drying them during four hours at 140 degrees. On lower floors the leather is dyed the color code 863, the NBA’s signature brown, to bring out a hide’s natural grain. Its pebble texture is embossed by a German-made plate the size of a small dinner table that uses 1,000 pounds of pressure.

The denser the hide, the better the pebble holds; it’s why the tannery’s graders write a hand-written “1” in the dense middle of the back, where Skip Horween had focused on. Some hides produce reams of NBA-quality leather, others only a little. Lower-graded areas produce those bound for the NBA’s developmental league, or retail shelves. It’s also why the choice of steers is intentional. Dairy cows’ hides are too stretched by birth — perfect for supple leather gloves, but bad for controlling a crossover dribble. Bulls’ musculature can leave too many wrinkles.

“One of the great challenges is, because every hide is different, you’re trying to take something that is un-uniform, each one, and make it as uniform as possible,” Horween said. “We’re providing marble, they’re doing the sculpture.”

This process was bypassed altogether in 2006, when the NBA and Spalding unveiled the most striking innovation to the game ball since its four leather panels became eight in 1970. Leather was out. Microfiber was in.

“It was a disaster,” Golden State coach Steve Kerr said.

Kerr didn’t think so initially. At the league’s request during the summer leading into the 2006 season, he and two other retired players, Mark Jackson and Reggie Miller, spent less than an hour testing Spalding’s “Cross Traxxion” model inside Madison Square Garden, “old guys just shooting around,” Kerr recalled. They returned a cursory thumbs-up review.

It was the most extensive feedback Spalding had sought before training camps opened, an error that became immediately apparent as soon as training camps opened and more rigorous play revealed the ball’s flaws. The material didn’t absorb moisture well enough, leaving it too slick when wet. When dry, players showing split and bandaged fingers said the new material created too much friction.

The players’ union filed two unfair labor practice charges with the National Labor Relations Board. Within two months, then-league commissioner David Stern recanted and brought back the leather model, an about-face Spalding officials learned of while watching the news, said Dan Touhey, a former Spalding marketing executive who worked closely on the transition.

One Cross Traxxion ball still exists in the collection of Washington’s National Museum of American History, where it is an example of “how not all adaptations are successful, revealing how the history of invention is not one of continued and unimpeded progress,” Eric Jentsch, a curator within the museum’s division of cultural and community life, wrote by email.

Touhey felt the material wasn’t “that far off.” Some offensive numbers had actually improved. But the players’ uproar did not fade, because it was aimed as much at the material itself as the feeling that players had not had a voice in the transition nor virtually any input amid its testing.

“We really should have worked with the players, we should have been in training camps, we should have been traveling around the country and early on there was a plan to kind of do that,” he said. “I think at some point David [Stern] just said, look, if Spalding believes in the ball and I have these retired players play with it with no issues, then I’m just going to make the decision.

“In hindsight we would have gone out and would have tested and would have stuck to that original plan.”

Unlike 2006, there were no concerns with the performance of Spalding’s basketballs in late 2019 when the company entered negotiations with the NBA to extend their partnership, said Salvatore LaRocca, the NBA’s president of global partnerships. Spalding vice president Matt Murphy, who declined to be interviewed, told the Philadelphia Inquirer the breakup after 37 years was mutual; Spalding continues to provide the league’s stanchions and rims. It “wasn’t one single thing,” LaRocca said, but he made clear the NBA wanted to raise its profile, and sales, abroad.

That was the opening Wilson, which produced basketballs for the NBA during its first 37 years, had sought since it lost the league’s basketball business in 1983. Employees who joined Wilson even decades later said co-workers would talk of the split as if the wound was still fresh.

“It would be guys like me and you standing around a water cooler going, ‘We got to get that NBA deal back,’” said Kevin Murphy, Wilson’s general manager of team sports. “‘How did we lose that? What did we do wrong?’”

Wilson is a subsidiary of Amer Sports, a Finnish conglomerate that, in 2018, was bought by a consortium led by Chinese giant Anta Sports. Wilson’s Chinese connections were not a focus during negotiations, according to LaRocca. Yet ever since Stern arrived in Beijing in 1987 and struck a deal to broadcast NBA games on Chinese Central Television, the league has spent decades building inroads there, to success and controversy.

“Certainly the NBA is extremely cognizant of the importance of China to its long-term growth,” said Jon Bogert, the editor and publisher of Sporting Goods Intelligence. “Anta has a huge retail footprint in China. I’d be willing to bet you’ll be seeing a lot of Wilson basketballs over there.”

The 10-year deal is expected to yield technological advancements as seen in the NFL, which has played with microchip-enabled footballs since 2017. The NBA has interest in gathering such a trove of data with chipped basketballs, too; Wilson’s Murphy said he expects it to happen within five years.

::

Fourteen miles west of Horween’s Bucktown neighborhood, on a street lined by warehouses underneath the flight path out of O’Hare International Airport, is a little-known building responsible for products seen by millions.

Inside Wilson’s research and development lab, dubbed the company’s “Innovation Center,” rackets made specifically for Serena Williams and Roger Federer line a wall next to cubicles for designers and mechanical engineers. Custom irons, woods and putters are milled in the back near the gray filing cabinet that houses the club measurements once used by VIP clients including Sammy Davis Jr. and former President George H.W. Bush. Next to the partial tennis court surveilled by spin-tracking cameras is a basketball court about one-third the regulation size, 3D printers and proprietary equipment that Krysiak, who runs the facility, cagily said he could not show off.

Only a few NBA players, such as Chicago All-Star Zach LaVine, visited here during the year-plus that Wilson spent testing different versions of its basketball, samples that tweaked the grip, channel depth and logos. But every player this season now touches a ball that was designed here.

“We wanted to make sure it just didn’t look like we ripped off the Spalding panel and put on ours,” Krysiak said. “Not a knock on Spalding and they did a great job but we didn’t want to be like, ‘They did all the R&D for us, we just overpaid for the NBA and now we get to put our logo on it.’ We wanted to make sure we definitely put our stamp on it.”

The trick was learning the line where Wilson’s ambitions and players’ acceptance met. To find it, the company surveyed and interviewed more than 300 players, at first remotely and later in person as pandemic restrictions eased, to find what they liked from Spalding’s model and where Wilson could make tweaks they deemed upgrades. Once the information was gathered, sample basketballs were created and mailed to players across the country before waiting to hear their thoughts on Zoom. Wilson’s Murphy said the company was extremely sensitive to the analysis. Players can’t be fooled, said Calderon,saying veterans can tell differences in the feel of a ball bounced at sea level, in Miami, versus the altitude of Salt Lake City.

The inclusion of player feedback earlier in the process was seen as a necessary corrective to avoid repeating the mistakes of 2006. But it also exemplified the closer relationship NBA Commissioner Adam Silver has sought to forge with the players’ union on labor issues compared to Stern’s more combative stances.

“Adam Silver was there in all the meetings and through all the controversy [in 2006]. He gets it,” Touhey wrote by email. “If anyone is going to make sure this new Wilson ball is successful, Adam is the guy.”

Reactions broke down generally on positional lines: Ballhandlers were quick to comment on grip and shooters the depth of its seams and channels. If one player voiced a specific criticism, it was weighed against the larger consensus, said Mike Kuehne, a global project director at Wilson whose 40-year career at the company began with a job selling the previous Wilson NBA ball.

“Every little detail was thought about,” said Calderon, who helped arrange the testing from the union’s side, calling it a “great process.”

“We were trying to get closer and closer to what the majority of players were saying until we find out what works.”

Krysiak estimated four to five rounds of samples were winnowed before a favorite emerged. Equipment managers for teams were later brought to the Ada, Ohio, factory where Wilson produces its NFL balls and stands as the last link of its NBA supply chain before balls are shipped to practice facilities. Graders weed out balls that are discolored, or fail to meet the NBA’s rigid guidelines covering weight and shape. Wilson also grades by 12 additional standards, separate from the NBA’s, a company spokeswoman said.

Yet balls that made the cut were still not a finished product. The league was about to break in new balls for the first time in 37 years, Wilson needed to know how it could speed up that critical process at Ada.

“We did a lot of work on that and spent a lot of money, frankly,” Murphy said.

One such step involves loading one ball at a time into a piston-powered machine, which pummels it for five minutes in an up-and-down motion designed to mimic a waist-high power dribble. Within Wilson, the device has been nicknamed “Scottie Piston.”

::

Last June, as draft prospects approached racks of balls inside Chicago’s Wintrust Arena at the league’s pre-draft combine and rubbed them between their palms, a group of Wilson officials watched silently nearby, noting every expression. A good sign was a player taking the first ball they felt to begin warming up, and it happened enough that officials left feeling that they had delivered, said Kevin Murphy, Wilson’s general manager of team sports.

By early September, weeks after each team’s allotment of 120 balls had arrived, two league executives said reaction was so muted to the transition to the new balls that they hadn’t heard a peep. Other team employees said a common consensus was that the balls took longer to break in but ultimately played nearly identically to the Spalding predecessor.

Touhey said the nature of change and his own experience in Spalding’s transition led him to expect that such high approval ratings wouldn’t last.

“Even though it’s a leather ball, the leather comes from the same leather manufacturer, even though the size and weight and everything is as close to the Spalding ball as possible, I guarantee you it’s not going to matter,” he said in September. “You’re still going to hear people saying, ‘Oh, it doesn’t feel the same.’”

It was a prescient thought. In October, minutes after Kerr echoed he hadn’t heard any ball complaints, his star guard Curry, the greatest three-point shooter in NBA history, nodded his head leaving the court in San Francisco after a shootaround when asked if he could feel a difference. He mentioned the balls’ “life span” feeling shorter, saying those used during opening night against the Lakers felt nearly bald compared to others he’d practiced with earlier. Some team employees wondered whether players would be reluctant to publicly criticize Wilson’s new basketballs out of fear of being labeled the worker who blames their tool. But quiet critiques like Curry’s soon spilled out into postgame news conferences.

Joel Embiid, the Philadelphia 76ers star, has blamed the ball on his poor shooting; Portland guard C.J. McCollum, the president of the players’ union, said in November that he wanted to hear more feedback; Paul George, the Clippers star, attributed the league’s offensive woes directly to a ball that doesn’t “have the same touch or softness that the Spalding ball had.”

Yet in a conflicting stance, one of George’s teammates, Reggie Jackson, said there were some practices this season where the Clippers could not miss. Another, Eric Bledsoe, said approvingly that Wilson’s ball has “a lot more grip.” If consensus has been difficult to entirely pin down, it has trended toward a feeling the ball plays little differently than Spalding’s. Mark Cuban, the Dallas Mavericks owner who commissioned a study by a Texas university’s physics department in 2006 to study the synthetic ball, posited in November that “when people talk about the ball being different, it’s not an excuse. It’s a reality that guys are going to have to adjust their approach.”

In September, as training camps opened, Wilson’s Murphy likened his hope for the new ball to the performance of a good official — hardly noticeable. He expressed confidence the company’s transparency with players had left it as prepared as it could be for its moment in the spotlight. He also acknowledged the ball could be used as “a good punching bag.”

“It’s the reason why we felt that partnering with the players from the beginning was going to be the key to getting the ball integrated as seamlessly as possible,” LaRocca said. “I don’t think that means that we’re not going to have players when asked about their opinion say that they might not feel the same to them or they like the other ball better and so forth.

“But I think that’s inevitable, I think that’s OK, as long as we know that we went through the process with the players and that the majority of the feedback has been, or we hope will continue to be, overwhelmingly positive.”

One-quarter of the way through the season, the volume of the criticism has grown quieter. In 426 games through Wednesday, the league’s average field-goal accuracy stood at 45.2% and its average three-point accuracy at 34.8%. Both stood as the lowest marks at the same point in a season since 2015-16, but by relatively small margins. Many around the NBA see last year’s record shooting numbers — 46.4% overall and 36.9% on threes at the same point — played largely in front of fan-free arenas, as the statistical exception.

Wilson has remained in contact with the league since the season’s start, a company spokeswoman said. In fact, it built a quality-control check right into the ball — an etched number specific to each that corresponds to a spreadsheet where the specifications of each ball that leaves the company’s Ohio facility are logged.

In a second-story office covered in wood paneling and leather, away from the tannery’s rumbling ground floor, Skip Horween stood at one of the earliest points in that supply chain, one with so many elements that it tempts Murphy’s Law at every step, Horween said. He rubbed a rough-bristled brush over an NBA-caliber ball, showing how heavy usage brings out the leather’s natural grip. Chicago’s United Center was less than four miles away, yet it would take months before the tannery’s leather would reach its court.

Before Horween joined his family’s business, he studied classics and archaeology in college. His leather now plays a central role in a process that is part art, part science and produces a ball whose creation relies less on automation than the judgments of dozens of humans along the way, from Horween’s first inspection on a rumbling tannery floor until the last player’s postgame review.

“The best athletes in the world,” Horween said, “can tell you the subtle differences in ways that you have to measure with a micrometer and equipment. They can just feel it.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.