Commentary: MLB owners and players can’t agree on solutions — or even the problems

It didn’t take long for MLB owners to impose a lockout once the collective bargaining agreement expired. It may take a long time before the game is played again.

- Share via

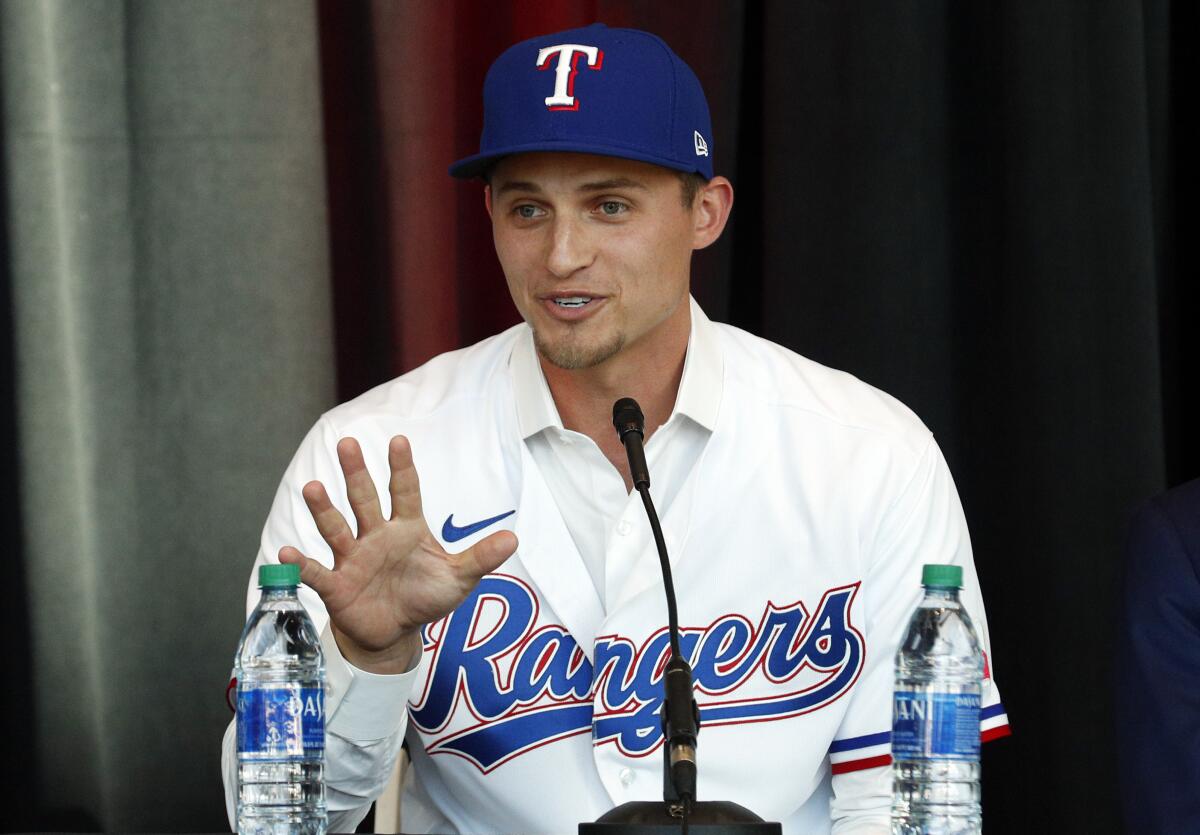

In the final hours before baseball as we know it shut down, Max Scherzer took a few minutes from his obligations to the players’ union to hold a news conference about why he signed with the New York Mets. Scherzer, however, did not pass up the opportunity to explain what the players prioritized in a new collective bargaining agreement.

“First and foremost, we see a competition problem,” Scherzer said Wednesday.

The clock struck midnight on the East Coast, the old agreement expired, and major league owners immediately imposed a lockout.

“This defensive lockout was necessary because the Players Association’s vision for Major League Baseball would threaten the ability of most teams to be competitive,” Commissioner Rob Manfred wrote in an open letter.

You can start to sense the hostility, and you can start to see the mess. If owners and players agreed that competition was a problem and disagreed on the solution, that would be one thing. This is worse: The players believe competition is a problem and believe they are offering ways to make things better, while the owners believe the players’ proposals would create a problem instead of solve one.

Why is the MLB headed toward a lockout Wednesday night? How long might it last? What are all the issues? Here are the answers to many of your questions.

Tell it to fans of the Baltimore Orioles. The Orioles have lost at least 108 games in each of the last three full seasons, finishing a combined 158 games out of first place. They have tried to lose, and at that they have succeeded, spectacularly. They also have killed attendance in a great baseball town.

When the Chicago Cubs won the World Series in 2016 and the Houston Astros followed in 2017, owners marveled at the efficiency: Lose for a few years, stock up on young talent in the process, and win!

But only one team can win each year, the Cubs and Astros are large-market teams that bought free agents to complete their rebuilding cycles, and in any case the winners since then have been large-market teams that resisted tanking: the Boston Red Sox in 2018, the Washington Nationals in 2019, the Dodgers in 2020, the Atlanta Braves in 2021.

This is no longer a model for the Pittsburgh Pirates to follow, if it ever was. The union wants to do whatever it can to discourage that model, in the interest of the game and in the self-interest of its veteran players who must take pay cuts if they can find a job at all.

In his open letter, Manfred said the owners had heard the union concerns and responded to them with proposals: a minimum payroll for the first time; an increased minimum salary; an NBA-style draft lottery so the team with the most losses would not necessarily pick first; free agency at a certain age rather than after a certain number of seasons so teams would not delay the start of a player’s career.

“Regrettably,” Manfred wrote, “it appears the Players Association came to the bargaining table with a strategy of confrontation over compromise. They never wavered from collectively the most extreme set of proposals in their history.”

The late Marvin Miller, the union leader who negotiated the first agreement under which players could become free agents rather than remain under the control of their original team, might have begged to differ. But what exactly did Manfred say the union wants now?

“Significant cuts to the revenue-sharing system, a weakening of the competitive balance tax, and shortening the period of time that players play for their teams,” Manfred wrote. “All of these changes would make our game less competitive, not more.”

Manfred is scheduled to hold a news conference Thursday, and he should explain why those proposed changes would make the game less competitive. When the union files a grievance over four teams that purportedly put revenue-sharing money toward profits rather than player salaries, when the luxury tax has become a de facto soft salary cap, and when the Colorado Rockies hold Jon Gray and Trevor Story rather than trade or sign them, Manfred ought to display league projections that show why less revenue sharing, a lower luxury tax and earlier free agency would make the game less competitive.

There is a middle ground on competition, somewhere between what the owners have offered and what the players have offered. Yet that obscures the dominant story line of this lockout: What the players fundamentally want to get is what the owners do not want to give.

Manfred noted that MLB has no salary cap, unlike other major sports, and players can negotiate a contract for as much money and as many years as they can get.

“We have not proposed anything that would change these fundamentals,” he wrote.

True, and yet owners have been quoted over the years about their reluctance to make certain moves to avoid paying a luxury tax. And, more critically, most players never see the free-agent riches Scherzer and Corey Seager and Chris Taylor were given this week.

Here is where owners have cornered players: Since analytics have shown owners that younger players have more value, the union wants younger players paid more. When the owners say they would reallocate spending toward younger players, the union says spending should be increased, not just reallocated, because revenues have gone up while salaries have not.

Checkmate coming: The owners could say, if the union wants salaries to go up when revenues do, that is what the NFL and NBA and NHL do. Those leagues pay players a certain percentage of salaries. That is called a salary cap, and the union has adamantly resisted one.

The owners are not even offering one right now, because their success at exploiting recent bargaining agreements have given them almost all the benefits of a salary cap without having to negotiate one.

In its statement Wednesday night, the union noted the league was not required to impose a lockout. The old bargaining agreement had expired, but the two sides could have agreed to keep it in place as negotiations continued.

“It was the owners’ choice, plain and simple,” the statement said, “specifically calculated to pressure players into relinquishing rights and benefits.”

If that is the case, it might work. Come the season, when players would start to get paid again, some players might pressure the union to cut a deal. Or some owners, anxious for full ballparks after two pandemic seasons, might pressure Manfred to cut a deal.

This shutdown is likely to be long. It would be a pleasant surprise if spring training started on time. It would not be a shocker if the regular season did not.

As soon as the league imposed the lockout, team websites removed news stories about and pictures of current players, so as not to use a player’s name, image or likeness for promotional or commercial purposes.

The Dodgers had a great day Wednesday, re-signing Taylor, a fan favorite, to a four-year, $60-million contract. On Thursday, we will hear not from Taylor, but from Manfred, and then from union chief Tony Clark.

Winter is no longer coming. Winter is here.

With the Dodgers losing Max Scherzer and Corey Seager in free agency, the team won’t have an easy road back to the postseason in 2022.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.