- Share via

PITTSBURGH — On a late summer evening in 1971, Manny Sanguillen heard his Pittsburgh Pirates teammate Dave Cash mention that something unusual was happening inside Three Rivers Stadium. No, not unusual. Unprecedented.

Sanguillen, the ebullient catcher and a native of Panama, stood at home plate and scanned the field. All of the Pirates on the artificial turf had something in common. Something other than their double-knit white uniforms with black and gold trim.

“We have nine brown people on the field,” Sanguillen said to himself, his amazement and delight still evident as he tells the story.

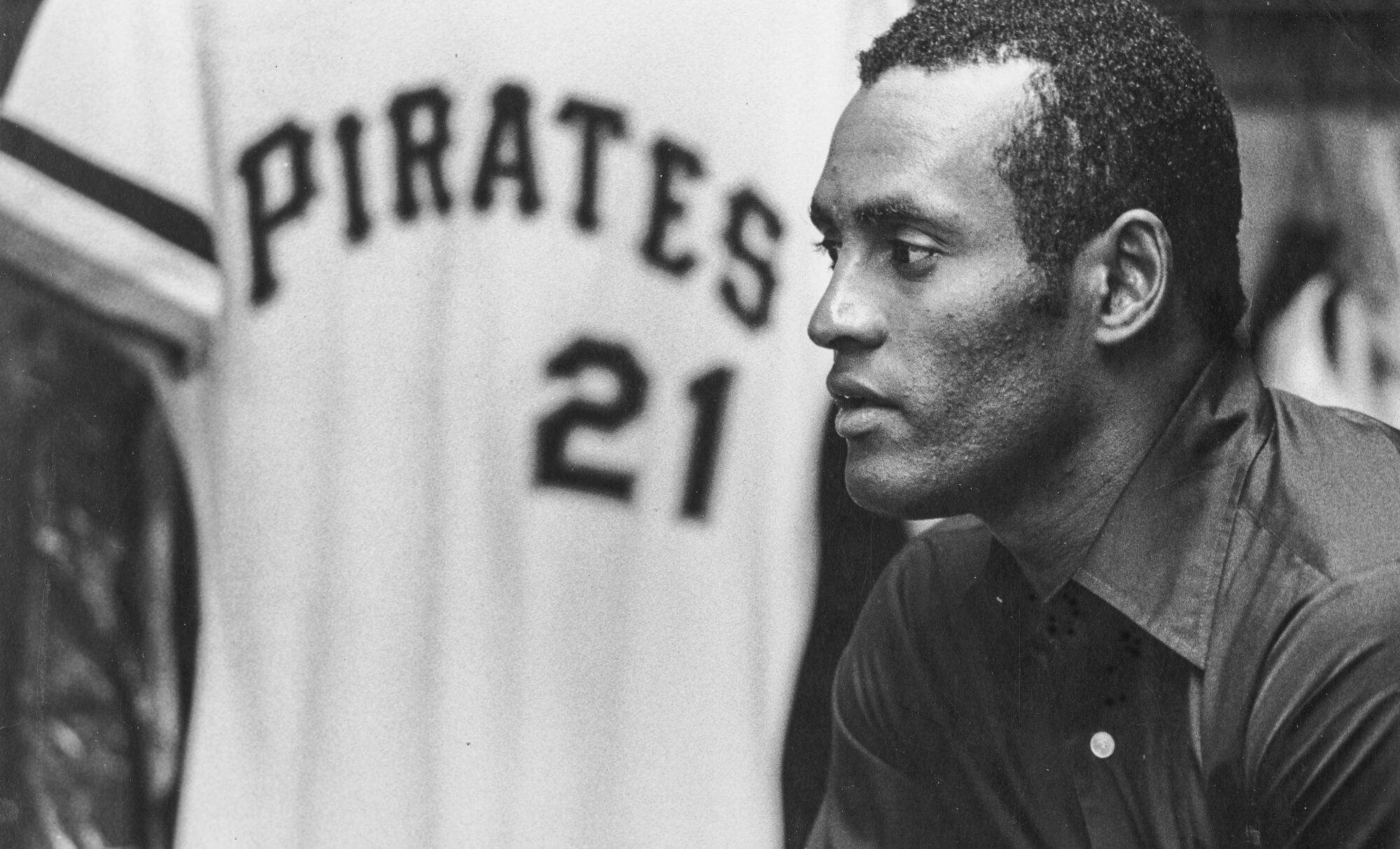

Sanguillen found his close friend Roberto Clemente, the Pirates’ right fielder from Puerto Rico, and pointed out the makeup of the lineup to take on the Philadelphia Phillies.

“We have to win this game,” Clemente said earnestly. “Can you imagine what they’ll say if we don’t win with all of us on the field?”

Twenty-four years after Jackie Robinson’s major league debut, a team had fielded a lineup consisting entirely of Black and Black Latino players. The Civil Rights Act had become law only seven years earlier, and battles over school desegregation still raged.

And now, on Sept. 1, 1971, a baseball team was quietly making a statement about diversity and what it means to be an American. The Pirates were not at all surprised that they were the team to take such a significant step.

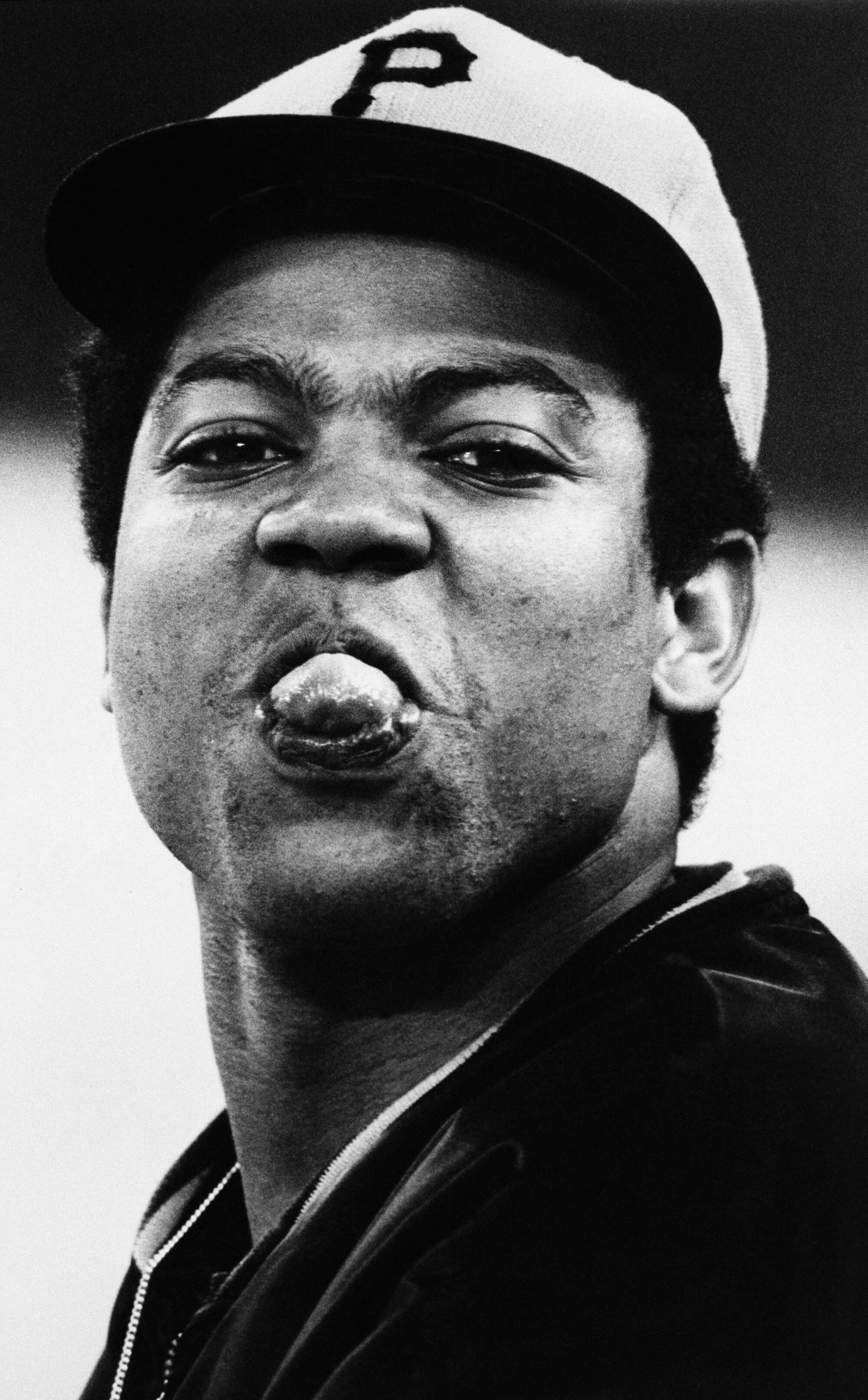

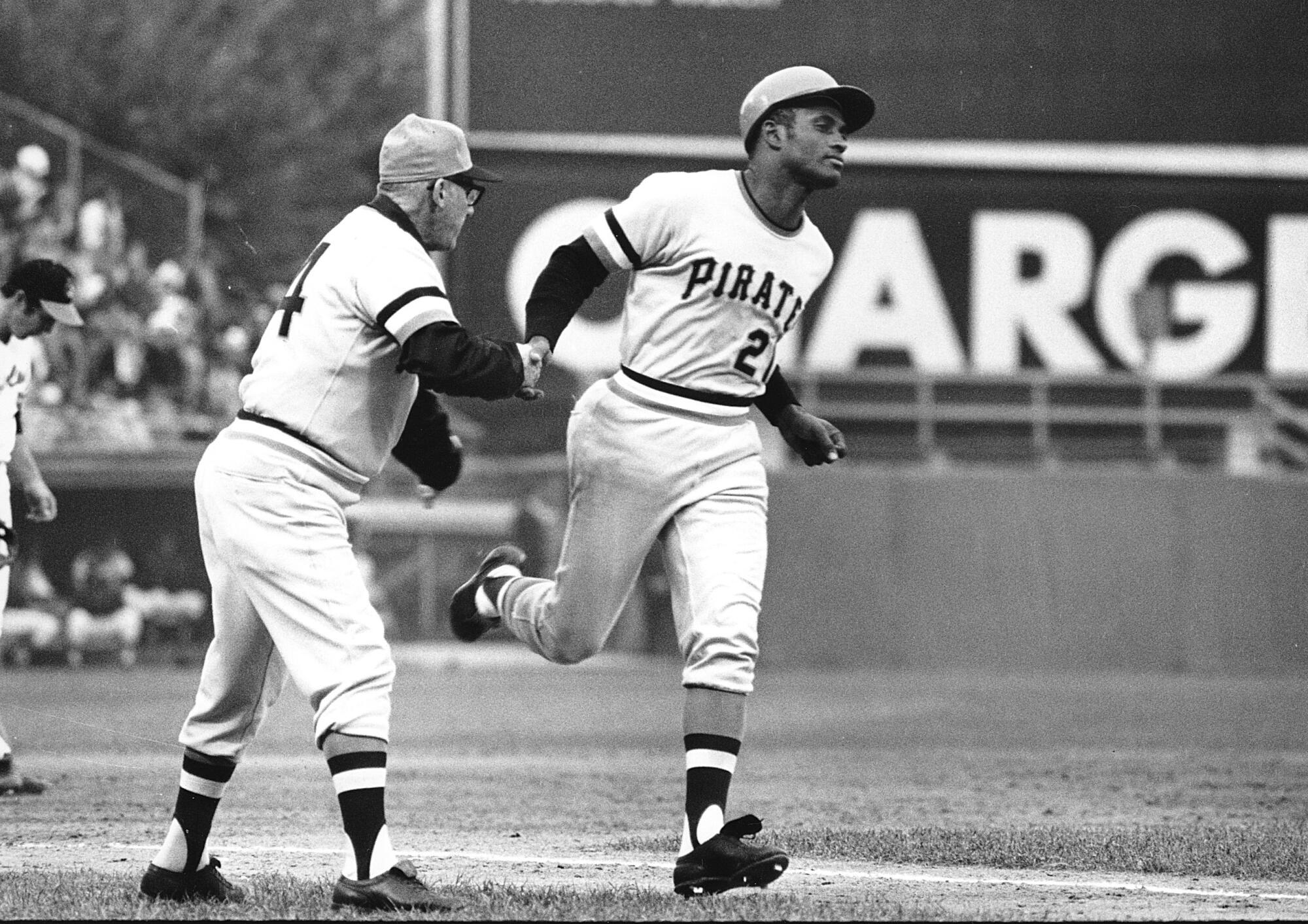

Pittsburgh’s lineup 50 years ago Wednesday included two future Hall of Fame players, Clemente and left fielder Willie Stargell, and four other players who were current or future All-Stars: Sanguillen, first baseman Al Oliver, third baseman Cash, and a Southern California native and a Gardena High School grad, pitcher Dock Ellis.

Rounding out the starters were shortstop Jackie Hernandez, second baseman Rennie Stennett and center fielder Gene Clines.

Back in 1971, free agency in baseball was still a few years away and general managers built teams through trades and drafting young prospects. That’s how the Pirates of the early ‘70s were constructed, but the organization had forged its own path within that framework.

“The Pirates had probably signed more Black and Latin players in the ‘60s than anybody in baseball,” Clines recalled. “They were the dominant force in Latin America.

“I can think of times before that night where we had seven or eight Black and Latin players on the field and it didn’t make a difference to us. Being with the Pirates, that was just the norm. We were there for one reason, and that was to win.”

Pittsburgh was leading the National League East Division, but the landmark game did not begin auspiciously for the Pirates. In the top of the first inning, an error on a ground ball by Hernandez allowed the Phillies to score the first run, and by the end of the half-inning, the Pirates trailed 2-0.

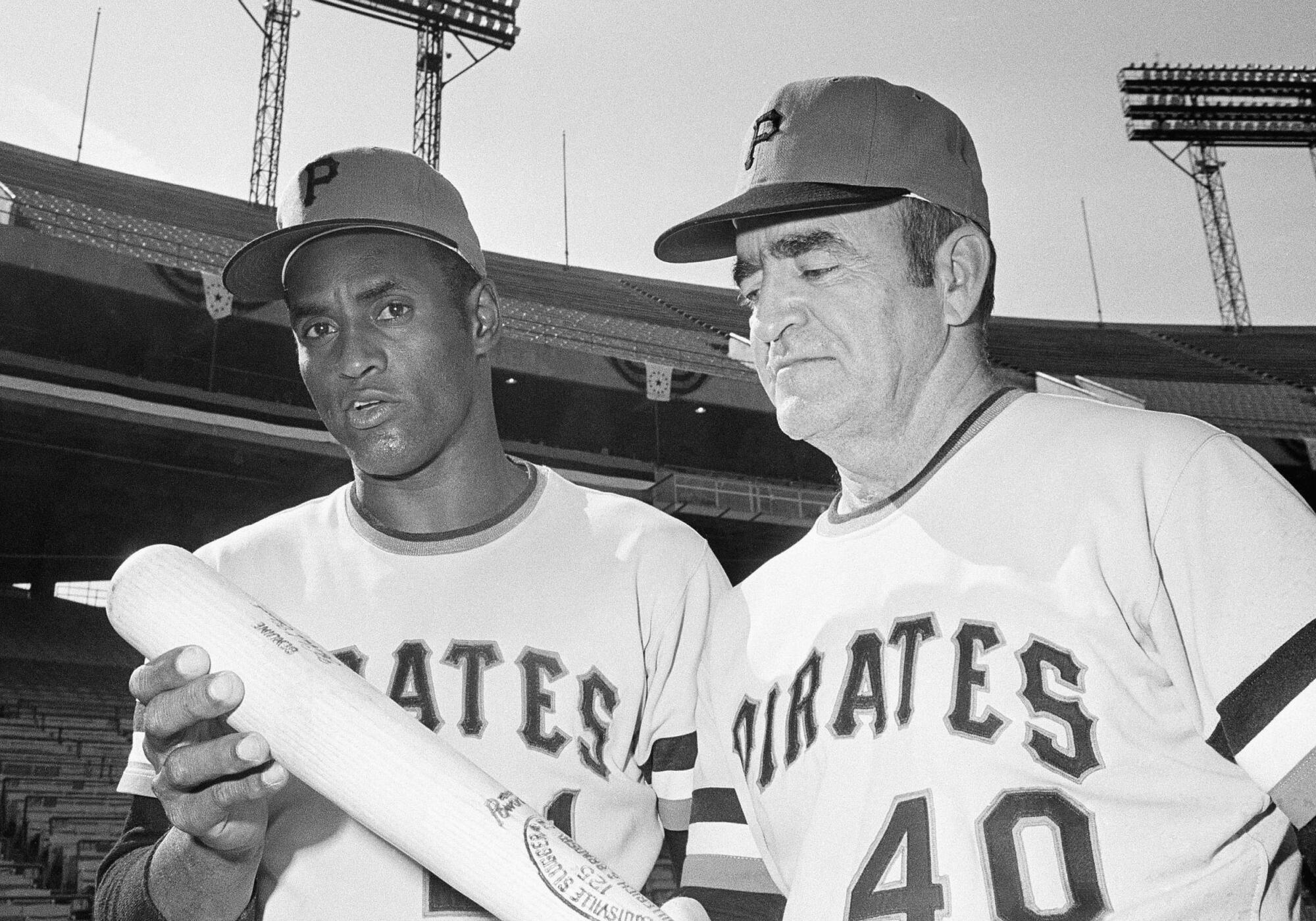

The man who made history filling out the Pirates’ lineup card that night was their manager, Danny Murtaugh. The even-keeled Irishman was in his third stint as Pittsburgh’s manager, having led the team to a World Series title in 1960, a seven-game triumph over the mighty New York Yankees.

Murtaugh had reached the major leagues playing for the Phillies in 1941. Like many major leaguers, though, his career would be interrupted by World War II.

Murtaugh hoped to serve in the Army Air Corps but was turned down, said his granddaughter Colleen Hroncich, who wrote a biography of him. The man who later would be praised by his players for being “colorblind” when it came to race could not fly airplanes because he was in fact colorblind.

“He had a chance to stay stateside and play baseball in the military, but he didn’t think he’d be helping very much if he did that, so he volunteered to join the infantry,” Hroncich said.

While serving in Europe, Murtaugh experienced intense combat. “Once his unit was pinned down by a sniper, and he later ... told my uncle, ‘I decided that if I got out of there alive, I wasn’t going to worry about anything anymore.’ ”

That philosophy served Murtaugh well in 1971, when he guided a collection of players from diverse backgrounds through the heat of a pennant race during one of the most turbulent periods in modern U.S history.

“The players said that because of all the unrest in the country at the time with race relations and the [Vietnam] War, his calming presence was well-suited to that team,” Hroncich said.

Cash confirmed that at a 50th anniversary reunion for the team in July.

“Race wasn’t a big deal to us. We had probably the closest-knit group of guys on any team that I played on,” Cash said. “We sacrificed for each other, and everybody loved each other.”

::

Forty years before that Sept. 1 game, having nine Black players on a baseball field at the same time in Pittsburgh was an everyday occurrence.

After all, the city was home to two of the most successful teams in the Negro Leagues, the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Some of the best Black ballplayers spent at least part of their career there, including National Baseball Hall of Fame members Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson.

“From a cultural and entertainment perspective, it was the major industry in Black Pittsburgh,” said Samuel W. Black, director of the African American program at the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh. “The major leaguers and the Negro Leagues players knew each other well from exhibition games. Only the conditions in this country at the time kept the Black and white players separated on the field.”

After Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, the Pirates were slow to integrate at first, Black said. However, that changed when they acquired Clemente in 1954; the Dodgers owned the rights to the highly regarded prospect but allowed the Pirates to select him and thus deprived Brooklyn, and later Los Angeles, of having one of baseball’s top outfielders for a generation.

“When the Pirates signed Clemente, it opened the door for them to sign more Latin players,” Black said. “In Pittsburgh, Roberto lived in the Black community. He embraced the Black community, and they embraced him.”

In 1971, Black was 10 years old and growing up in Cincinnati, and even though he and his friends were Reds fans, they developed a keen interest in the Pirates that season.

“I read about the Pirates in Jet magazine,” Black recalled. “They became part of my consciousness, and when we would play ball at the park, we would imitate some of their players. ... One guy who was left-handed and played first base imitated the hitch in Willie Stargell’s swing, and another guy would imitate Clemente’s gait as he ran around the bases.”

“It was a fact that ... African Americans across the country became fans of the Pirates. We just saw players who looked like us.”

Although the Pirates were the first franchise to field an all-Black lineup, Black players were making a significant impact on other teams too.

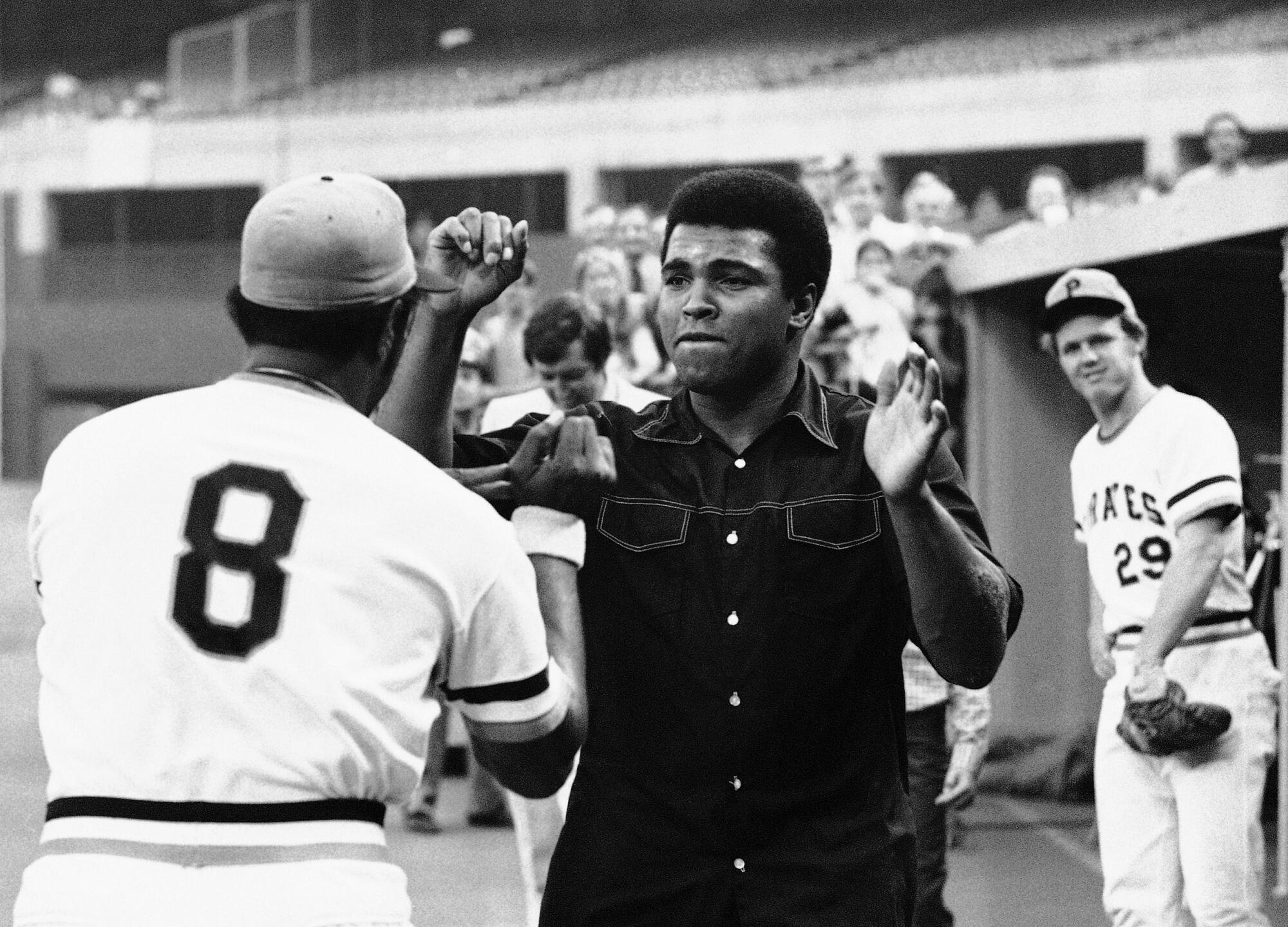

“The ‘70s were really a high point in terms of Blacks in Major League Baseball,” said Todd Boyd, a professor at USC and an author and commentator on race and popular culture. “We were accustomed to seeing Black players, and some of the biggest stars in the sport were Black: You had Hank Aaron; Willie Mays, who was near the end of his career; Reggie Jackson was an up-and-coming star; Vida Blue.”

Still, having one of the older franchises in the majors start a game with an all-Black lineup elevated the topic of diversity in baseball.

“In the early 1970s, baseball was a very popular sport and many people would have readily identified it as the national pastime,” Boyd said. “If you look at the impact of baseball in American culture at the time, to have the Pirates field an all-Black lineup, it’s noteworthy. It spoke to a change in the culture and way people viewed race.”

The sports landscape, and baseball’s standing, has changed dramatically since then. The NFL and NBA, for example, are much more prominent than they were in 1971. And although the total Major League Baseball attendance for 2019 was 68.5 million, that was a 14% drop from its high in 2007.

What’s more, in recent years American-born Black players have made up only 7% to 8% of major league rosters. (Latino players surpassed Black players as the second-most dominant race/ethnicity in baseball in the 1990s.)

Looking back at that Pirates-Phillies game, Boyd said: “Ordinarily, you would look at this moment and say this is when everything changed, but in this case, it didn’t. There has been a culture shift since then. Baseball looks old and conservative, and it embraces being old and conservative.”

On that historic night in 1971, the Pirates’ all-Black lineup was a topic of conversation in their dugout, but thoughts quickly turned to bouncing back from that early deficit to the Phillies.

“We knew we had put ourselves in a hole, but with that offense, we knew we were never really out of a game,” Cash said.

Indeed, the Pirates answered with five runs in the bottom of the first and three runs in the second and went on to win 10-7. Seven players drove in runs, including Sanguillen, who hit a two-run homer that brought in Clemente.

Pittsburgh’s two daily newspapers did not cover the game because their labor unions had been on strike for nearly four months, but a few of the reporters who were present realized that Murtaugh had made history.

“The writers ran in after the game and said to Danny: ‘Do you know what you did? You started an all-Black lineup,’ “ said Steve Blass, a veteran starting pitcher. “And Danny said: ‘I didn’t know that. I thought I was putting the best nine Pirates out on the field tonight.’ It was the perfect statement.”

The Philadelphia newspapers had varying reactions to the milestone. The Evening Bulletin published a headline that read, “Pirates’ Lineup All Black.” The Daily News made one reference to Pittsburgh’s “all-soul” lineup without elaboration. The Inquirer did not mention the racial makeup of the Pirates’ starters.

A United Press International wire story focused on the all-Black lineup and quoted Murtaugh: “When it comes to making out the lineup, I’m colorblind and my athletes know it.”

Over the next several seasons, Black players continued to play key roles in the Pirates’ success. Sanguillen, Stargell, Stennett and Oliver led the team to more division titles, even after Clemente’s death in a plane crash in 1972. The Pirates’ diversity became less noteworthy in time, though, and injuries and adjustments to pitching rotations made an all-Black lineup less likely.

The 1971 Pirates went on to the World Series, where they faced the defending champion — and heavily favored — Baltimore Orioles.

In the decisive Game 7, Blass pitched nine stellar innings and Clemente hit a home run. Hernandez handled a bouncer flawlessly and threw to first base for the final out. The Pirates won 2-1.

“The underlying legacy is that this turned out to be the best team in baseball that season,” Boyd said. “They proved that it was the right decision to play those guys by winning the World Series. That’s the ultimate endorsement.”

That wasn’t all they accomplished, Black said: “That ’71 Pirates team fulfilled the promise of Negro Leagues baseball.”

Even in a year in which his team won the World Series, the night of Sept. 1 stands out for Sanguillen, who played in 29 postseason games in his 13 big league seasons.

“It means everything,” he said. “It was the most beautiful game I ever caught in my life.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.