- Share via

He wanted to hand-deliver the card because Mother’s Day was approaching and Mom was heading out of town.

So Colt Brennan joined his parents at the family home in the hills above Irvine, four months into the five-month substance-abuse treatment program that was giving back to the Brennans their only son.

His mood practically danced, remembered Betsy, who noticed, too, the shine that had returned to Brennan’s green eyes.

“He didn’t want to leave,” she said. “He stayed and stayed until Terry had to drive him back.”

Terry, his father, and Betsy would be heading to Mexico in the morning for a wedding. They’d be back on Sunday — Mother’s Day — but Betsy already was holding her gift.

“I hope you have an awesome Mother’s Day weekend,” Brennan had written in the card. “I’m finally starting to find my way.”

He closed by expressing his thanks and his love and signed “XOXO.”

Nothing hinted at what would happen next. Nothing but Brennan’s decade-plus struggle with drugs and alcohol, a struggle that left a former quarterback once famous for swiftly advancing his team great distances limping and leaning on a cane.

When Terry and Betsy returned from Mexico that Sunday afternoon, they were stunned to find their son there, in the family room, empty beer cans and two vodka bottles nearby. Brennan offered few words, his appearance saying much more. He had left the live-in treatment center in Costa Mesa and, as Terry would later say, “returned to the dark side.”

After a rainbow-brilliant three years at the University of Hawaii and an NFL career that fizzled, Brennan’s existence became a series of failed starts to rediscover peace and chase away his tormentors.

Now, they were back, and what followed were roughly 12 chaotic, frustrating and bewildering hours that would end Brennan’s struggle and his 37 years of life, leaving those around him to ponder how a kid who produced so much magic in paradise died as a grown man going through hell.

Colt Brennan’s unlikely burst across college football’s horizon began in a manner just as unlikely.

Hawaii assistant coach Rich Miano had visited Saddleback College in Mission Viejo to scout a wide receiver, Jerard Rabb.

While rewatching video of Rabb, Miano noticed the whip-armed quarterback serving him all those spirals. Miano walked the tape down to the office of the head coach. He recalled June Jones rewinding one play again and again, maybe 10 times, before blurting, “Rich, this guy’s unbelievable.”

The utter precision radiated and Jones, a quarterback aficionado approaching 40 years as a coach, declared Brennan “one of the most accurate passers I’d ever seen.”

But all that big-time potential was tucked away at Saddleback, a tiny community college, for a reason. After starting for one year at Mater Dei High and playing a season at Worcester Academy in Massachusetts, Brennan redshirted as a freshman at the University of Colorado.

In January of 2004, he was involved in a drunken incident in a room of a female student, who said he arrived uninvited and began fondling her before a friend intervened.

A jury convicted Brennan of unlawful sexual contact, but a judge later dismissed the charge. Brennan instead was found guilty of second-degree burglary and first-degree criminal trespass and kicked out of school. He was sentenced to seven days in jail and four years probation.

“He never got over that,” Betsy said. “That haunted him.… That was one of his demons.”

While at Saddleback, an opponent sacked Brennan and punctuated the hit by spitting, “Rapist.” Brennan would later say other opponents intentionally stepped on or kicked him.

Throughout the rest of his life, he suggested the Colorado incident was misconstrued and overblown. He repeatedly expressed his innocence, most recently on Instagram in April.

So the islands offered Brennan what islands often do — an escape. And Jones offered an opportunity, a chance for him to walk on and prove himself as a quarterback and, more important, as a person before any assurances of a scholarship.

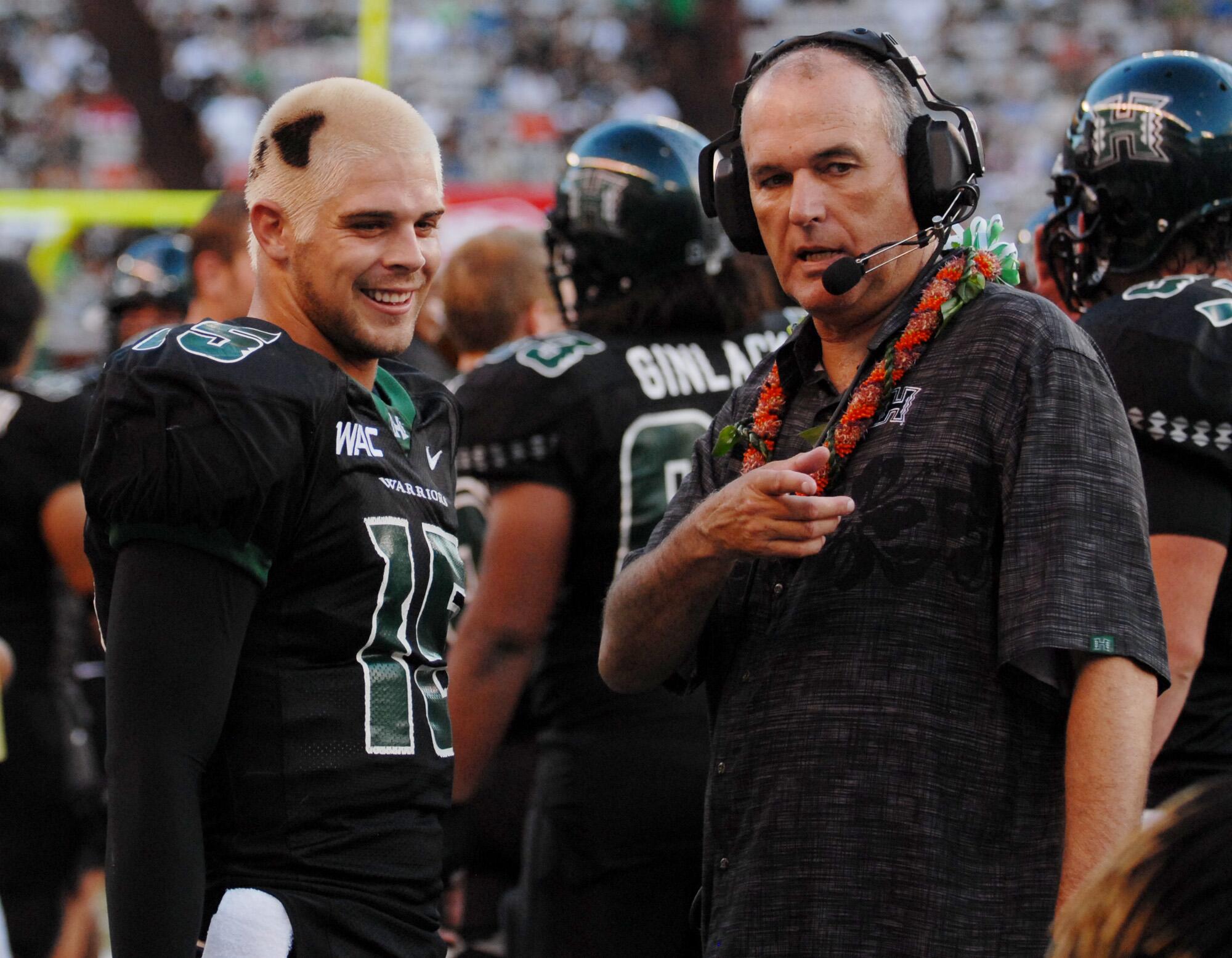

Brennan responded by lifting Hawaii, the football team and perhaps the state, to levels not seen before or since. He set an abundance of school and NCAA passing records, made his No. 15 jersey a marketing tool and turned Rainbow Warriors home games into can’t-miss, late-night ESPN programming. Most significant of all, Brennan embraced a place that so eagerly hugged him right back.

“My buddy once said, ‘If you put Tiger Woods, Tom Brady and Colt Brennan in an autograph session in Hawaii, the lines would be equally as long,’” Miano said. “We’ll never see anything like that again in our lifetimes in terms of popularity of a college athlete in this state.”

In December of 2007, the 12-0 Warriors were ranked No. 10, the highest position in school history. Hawaii football has appeared in the top 25 only twice since and never higher than 24th.

“That person has to want to help themselves or you’re never going to beat it. Colt struggled with that.”

— Former Hawaii coach June Jones

Success, though, came at a cost. Since his Mater Dei days, Brennan often had held on to the ball as long as possible, buying time to allow the magic to happen. As a result, he absorbed some punishing shots.

Once, while scrambling, he was drilled in the head by a Fresno State linebacker. Brennan wobbled off the field, braced against the shoulder of an athletic trainer.

Asked how many concussions he believed his son suffered over time, Terry answered, “He had enough.”

Brennan finished his Hawaii career with 131 touchdown passes and 20 400-yard performances. He threw for seven touchdowns once, six touchdowns three times. He passed for 14,193 yards, slightly more than eight miles.

“There have been popular athletes here,” Miano said. “But the Colt Brennan phenomenon was larger than life.”

All this island love for a mainlander — a white kid from Orange County, no less — but one who meshed remarkably well. Brennan once dyed the map of the Hawaiian Islands into his hair. In an attempt to bond with his receivers, he grew mini dreadlocks.

He would make checks at the line of scrimmage speaking Samoan, a nod to his offensive linemen. Brennan became popular for buzzing around campus on a scooter and flashing the shaka hand salute at everyone calling out to him.

“He was this Cali kid, had this surfer dude look, rad and all that,” said Breiden Fehoko, whose father, Vili, was an entertainer and, at the time, played the role of Hawaii’s warrior mascot. “He was like a god to some of us kids out there.”

Brennan, known for his warm smile and easy demeanor, rode the Hawaiian vibe like a wave. In 2007 he told The Times that if football didn’t work out, he’d “find a nice little hut and chill out for the rest of my life.”

Fehoko would grow up to play at LSU and now is a defensive lineman for the Chargers. He still has a wristband Brennan gave him after one game and the childhood memories of a “haole,” a non-Hawaiian, who was viewed as anything but.

“What made Colt so lovable was he just embodied the culture,” Fehoko said. “Colt didn’t have an ounce of Hawaiian blood in him, but he had 100% Hawaiian spirit in him.”

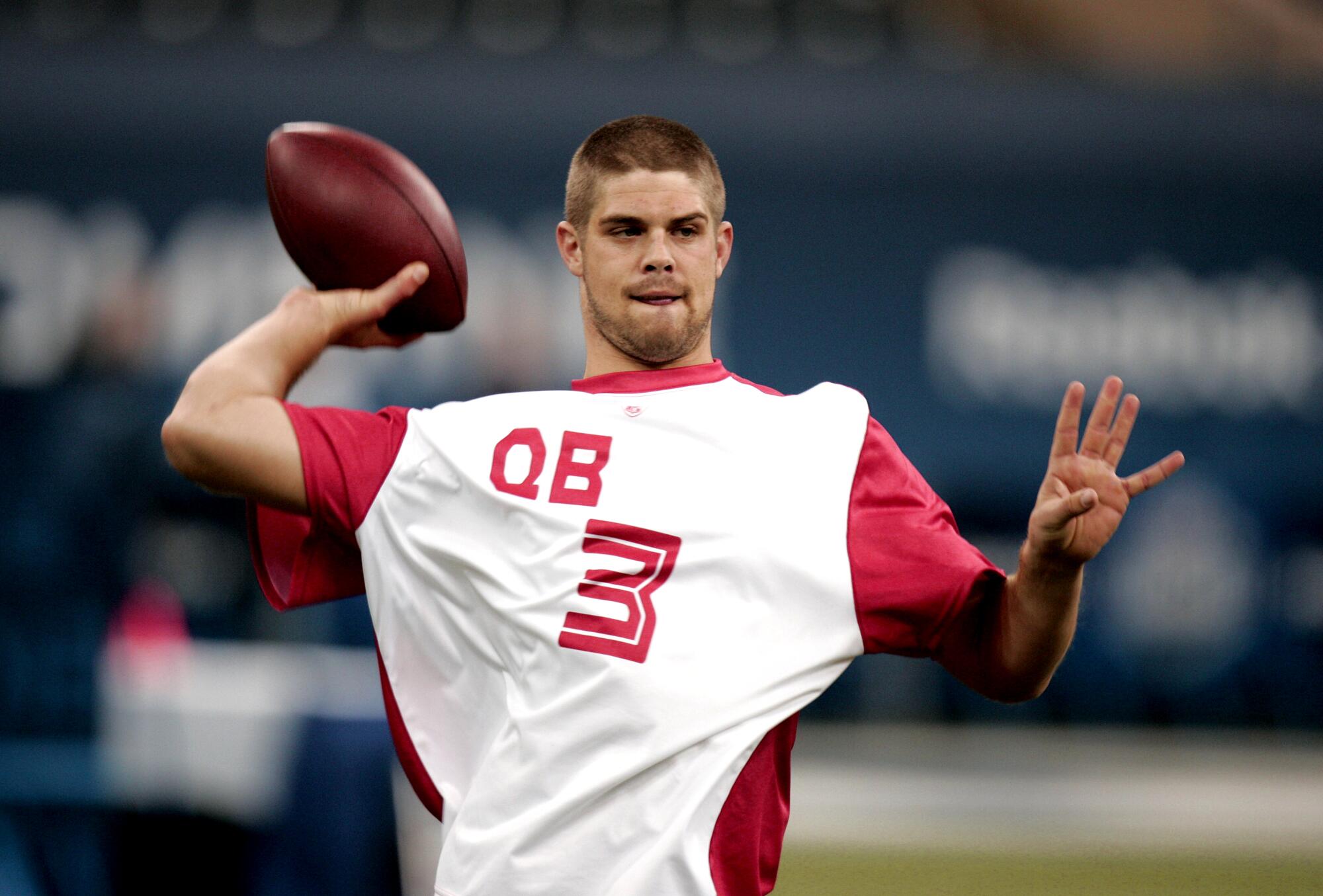

If this were a fairy tale, NFL stardom would have been the next chapter. But the book on Brennan as a pro was staggeringly short.

A sixth-round pick in 2008, he spent one year as Washington’s No. 3 quarterback before hip and hamstring injuries ended his second season before it began. A one-month stint with the Oakland Raiders in the 2010 preseason marked the balance of Brennan’s NFL career.

He retreated to Hawaii, where his story took a violent twist. En route to play beach volleyball, Brennan was riding in an SUV driven by his girlfriend when they crossed the center line, causing a head-on collision.

The damage included head trauma and left Brennan more moody, depressed and impatient. Years later, he’d say, “I woke up and I was, and I still am, a different person.”

He had lost football — “his whole life,” Betsy said — and soon lost his girlfriend, the couple breaking up. He was using drugs and drinking, and those behaviors intensified. Three attempts to return to football in lesser leagues ended in washouts. Brennan wouldn’t or couldn’t engage. The quarterback with the elite arm was now authoring a different sort of spiral.

He had support on the islands and back in California, but Brennan too often turned the other way.

“That person has to want to help themselves or you’re never going to beat it,” Jones said. “Colt struggled with that. Everybody out here tried to help him. We were all hoping we wouldn’t be reading about him like this some day.”

There were nearly a dozen incidents in Hawaii involving the police, many of them fueled by Brennan’s substance abuse. He faced multiple DUI charges and pleaded no contest once. He was charged with filing a false report when he claimed his car had been stolen, the case later dismissed. During a four-month period toward the end of 2020, he was arrested twice for causing a drunken disturbance.

Brennan’s health deteriorated. Blood clots filled his legs and he had trouble walking. When Brennan visited practices at Hawaii, he usually had to be shuttled around in a golf cart and steady himself against the cart to stand.

He became easily agitated waiting in line at the grocery store and complained how difficult it was to complete basic tasks, such as showering or doing laundry.

Betsy estimated her son spent time in perhaps a dozen treatment facilities in California, Utah, Arizona and Hawaii, never staying longer than a few weeks.

His experience at the Centre for Neuro Skills in Bakersfield was typical. Brennan got ahold of some marijuana and walked out, heading down the street to a liquor store.

“He’d just burn out after a month or so and we’d say, ‘Oh, no,’” Betsy said. “He’d just sabotage himself. That’s what he did. He sabotaged everything.”

Tough love. Strict boundaries. Real consequences. Brennan’s family and friends tried them all. He only resisted.

Frequently, Brennan lashed out with hateful text messages or nasty posts on social media, savaging the very people trying to save him.

“All that stuff, all those texts and the things that were said, were not Colt,” Jones said. “That was the drugs speaking. We all understood that.”

Last August, Brennan turned 37, but his behavior was aging his body faster than that. Having played at slightly more than 200 pounds, the 6-foot-3 Brennan now was noticeably bloated.

It was last fall when Terry decided to bring his son home. His parents would give him another chance by taking away his excuses, no more missed doctor or dental appointments. He responded with a three-page, single-spaced letter, emailed to his family:

I want to come home because life has been difficult for me and I’m tired. I know I can make you proud again. I know I can do this.

And for four months, he did. Brennan was smiling again. He was funny and attentive, telling stories and reciting lines — word for word — from his beloved Ace Ventura movies. He looked leaner, healthier. By all accounts, he was starring at the treatment center in Costa Mesa, even mentoring others.

“We were stunned because all of a sudden it was that serious. That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, my God. This is it.’ ”

— Betsy Brennan on her son being on life support in the hospital

But then came Mother’s Day and those 12 bewildering hours between the time his parents walked in to find him intoxicated in their home to the time Brennan ended up at an $80-a-night motel in a blighted part of Costa Mesa. He apparently took an Uber there.

What the family doesn’t understand is how he was able to do so. They thought he was in Newport Beach, at the Hoag Hospital detox facility, where Terry had taken him. Instead, the hospital had released Brennan shortly after 1 a.m. because, his parents said they were told, there was no room available.

“How could they do that, especially in the condition he must have been in?” Brennan’s sister, Chanel Brewster, asked. “It makes us mad. We just don’t want that to happen to someone else.”

Hoag did not respond to requests for comment.

Brennan was given a bus pass and a Post-it note with the name and phone number of another facility. He chose to use neither.

About 3½ hours later, police and paramedics were called to the Sandpiper Motel because of an overdose. Brennan was found on the floor, unconscious.

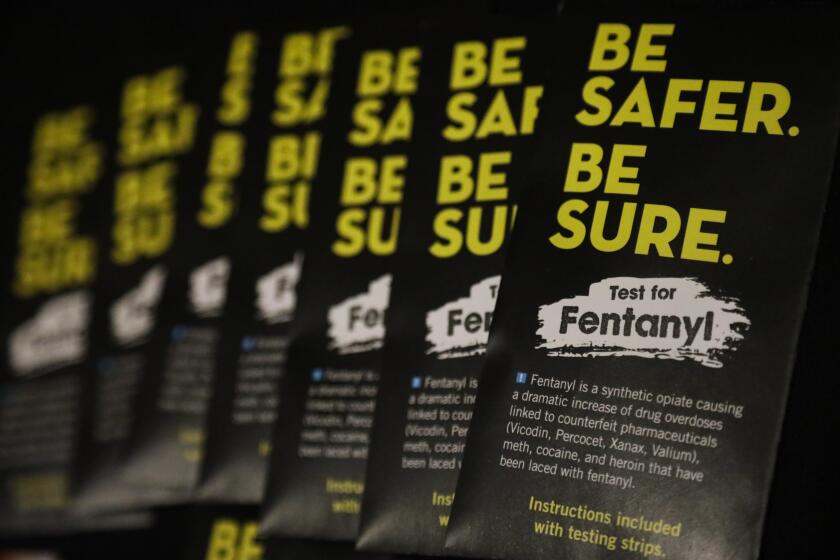

Two other men were with him, police told his family, but it was unclear if they knew one another before that night. An investigation continues. The initial evidence indicated Brennan had ingested something laced with fentanyl, a revelation Terry called “shocking.”

Just weeks earlier, Brennan had talked to one family member about the dangers of the drug. Chanel also recalled a family dinner where Brennan referenced fentanyl’s potency.

Sometime around 5 a.m., Terry received a call from Hoag and was briefly confused while it was explained that his son had left the hospital but was now back and under emergency care.

When Terry and Betsy walked into his room, they discovered Brennan hooked up to a ventilator while the machines around him, unbeknownst to them initially, detected little if any brain activity.

Betsy, unsure what to say in a mass email she wanted to send relatives, was told to report that he was on life support.

“We were stunned because all of a sudden it was that serious,” she said. “That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, my God. This is it.’”

Soon, Chanel drove up from her home in Oceanside. Brennan’s other sister, Carrera Shea, flew in from Colorado, arriving about 8 p.m.

Former Hawaii QB Colt Brennan ingested something laced with fentanyl before dying. The drug has been linked to a high number of opioid deaths in the U.S.

They spent the next few hours remembering stories and taking turns reassuring Brennan how much they all loved him. Chanel scrolled through her phone to find songs by his favorite artist, Bob Marley.

She also played a video — full of well wishes and highlights from Brennan’s career — that was put together last year by a Facebook group in Hawaii called “Ohana for Colt.” On Brennan’s chest, his family placed a lei.

Just after midnight, the decision having been made to end life support, he was gone. Brennan lived three minutes into May 11, dying 40 years to the day after Marley died.

Jones called the end “kind of inevitable.” Miano, who discovered Brennan at Saddleback, said he remembered telling others, “We’re all going to wake up some day and he’s going to be on the front page again and we’re all going to cry.”

Brennan was cremated, half his ashes buried with his grandfather in Corona del Mar and the other half destined for Oahu.

His brain has been sent to the CTE Center at Boston University, the Brennans hopeful to perhaps find some answers that remain elusive.

For now, they can only cling to the best memories and the hope this tragedy can be someone else’s salvation.

“I hate it to think that other people are going through what we did because it was awful,” said Betsy, a shiny No. 15 pendant dangling from her neck. “But they are. There are a lot of families out there doing the same thing. It’s just so tiring, so draining. It’s always hanging over you.”

Said Terry: “Just try to get help, try to reach out. Don’t be afraid to reach out and ask. There are no do-overs with this stuff.”

A few hours after burying the remains of her son, Betsy was in the kitchen with her two daughters and a friend. Suddenly, her phone, sitting a few feet away on a table, began playing “Three Little Birds,” a Bob Marley song that begins, “Don’t worry about a thing, Cause every little thing gonna be all right.”

The women looked at one another.

Said Betsy, “I don’t even know how to load music onto a phone.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.