Masters honors trailblazer Lee Elder by paying it forward

- Share via

AUGUSTA, Ga. — Augusta National welcomed him. The restaurant did not.

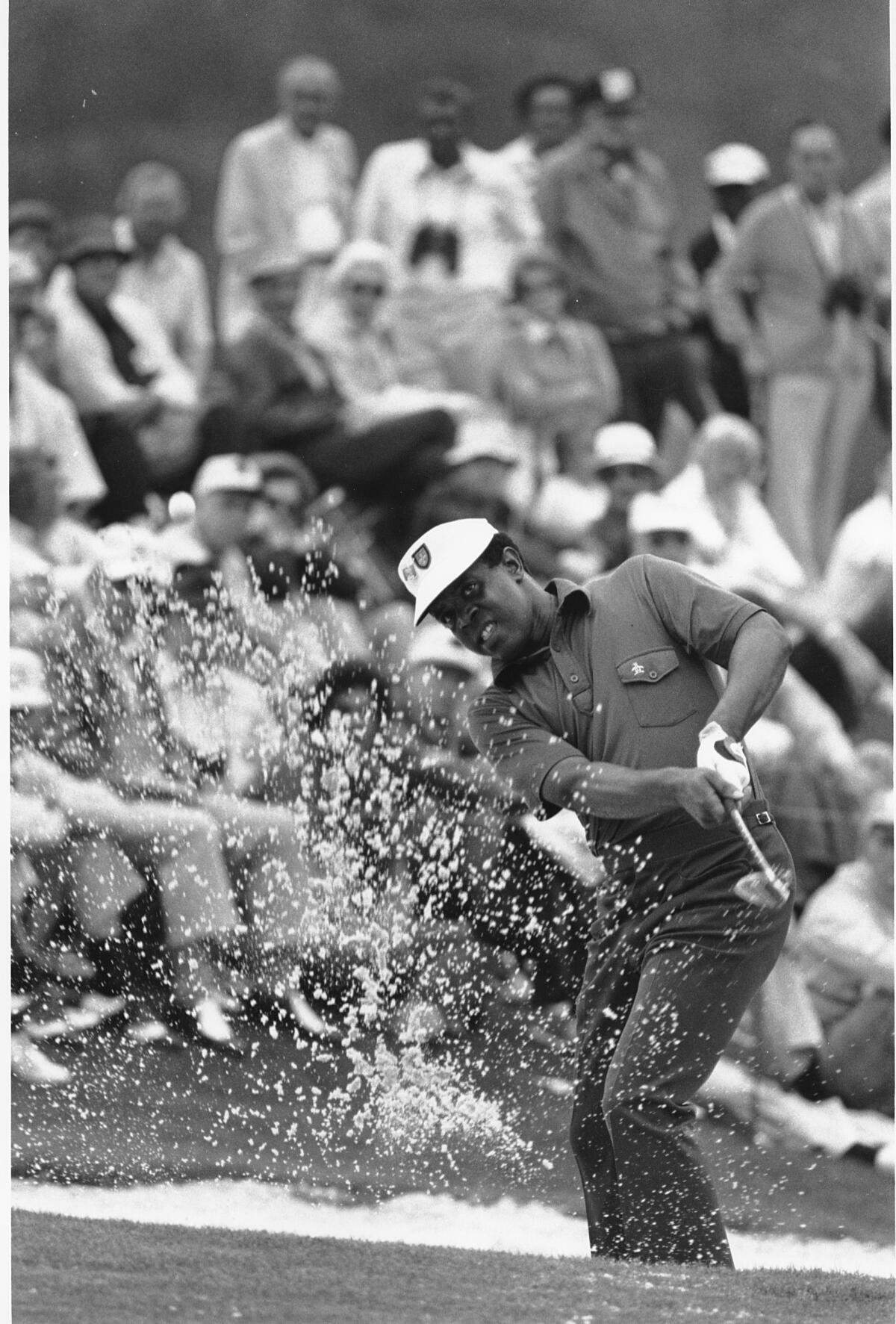

It was 1975, and Lee Elder was a pioneer, the first Black golfer to play in the Masters. But during the week leading up to the tournament, he and friends who had joined him on the trip from Washington, D.C., were denied service at a local establishment because of their race.

Upon hearing that, Dr. Julius Scott, then the president of Paine College in Augusta, Ga., told Elder and his friends that chefs from the school would be preparing their meals for the rest of the week.

“He took us under his wing,” recalled Elder, 86, who did not attend the historically Black college but feels a deep connection to it.

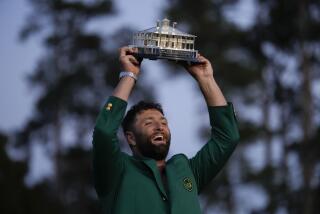

Elder, who lives in Rancho Bernardo, Calif., was honored Monday for his trailblazing and courageous contributions to the game. Augusta National will endow two Paine scholarships in his name and cover all costs of the school’s men’s and yet-to-be-launched women’s golf programs.

“We hope that this is a time for celebration,” Augusta chairman Fred Ridley said, “and a time that will be a legacy, create a legacy, not only for Lee but for us that will last forever.”

‘We hope that this is a time for celebration and a time that will be a legacy, create a legacy, not only for Lee but for us that will last forever.’

— Augusta chairman Fred Ridley, in honoring Lee Elder

Additionally, Elder will join legendary Masters champions Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player on the first tee for the honorary start of the 2021 tournament on April 8.

“Like all organizations, we’ve been moved by the events of 2020,” Ridley said. “There’s been a lot said about racial justice and opportunity, and our question was not so much what can we say but what can we do. So I guess I would say that this announcement is in part a call to action in that regard.”

Dr. Cheryl Evans Jones, president of Paine, called the development “a tremendous boost to our athletic program,” particularly during the pandemic when raising funds is especially difficult.

Sergio Garcia pulled out of the Masters on Monday after he tested positive for the coronavirus, becoming the second player to withdraw following a positive test.

Ridley said the expense of starting a women’s golf program at the school is irrelevant.

“We will fund 100% of whatever that cost is,” he said. “And when is it going to start? The efforts are going to start this afternoon.”

Elder, who attended the news conference at the club and later spoke to reporters while sitting in a chair just off the first tee, needed a cane and some assistance to walk. But he was quick to note that despite recently suffering a knee injury, he would be ready for his ceremonial drive in five months.

“I fell and hurt my meniscus two weeks ago,” he said. “It was a bruise. I got cortisone before I flew here. My doctor said that in about four weeks at the most it will be healed, and I’ll be back to hitting the golf ball.”

The path that led him to Augusta 45 years ago was arduous for a different reason. The start of his career in the late 1960s coincided with an especially turbulent time in race relations. He was derided, threatened and demeaned as he rose to prominence as a player, including some memorable indignities. At one tournament, he was forced to change shoes in the parking lot because he wasn’t allowed inside. Another time, he couldn’t find his ball because a spectator had tossed it into a hedge.

Six years into his PGA Tour career, he qualified for the 1975 Masters with a tournament victory in Pensacola, Fla., a win at the very course that once had denied him entry to the clubhouse. Fearing for his safety, he rented two houses in Augusta that year so people wouldn’t know exactly where he was staying.

“Yes, I did have threats,” he told CNN in 2015. “It was frightening. You try to eliminate the possibility of anything happening.”

At the tournament, patrons gave him a warm reception, cheering him down the fairways, at times rising out of their chairs to give him a standing ovation.

In his first round of his first Masters, Elder steeled his nerves and shot a respectable two-over-par 74. He failed to make the cut that year but qualified for the tournament the next five years in a row, tying for 19th in 1977 and tying for 17th in 1979.

Tiger Woods showed from an early age he had the confidence to be a golf champion: “I want to win all of the big tournaments, all of the major ones.”

For him, the excitement of riding through the gates and up to Augusta National never faded — even Monday when he did so as an honored guest.

“Driving down Magnolia Lane, that’s a memory that nobody forgets,” he said. “No matter how many times you come here, that’s always the fond memory. I know it is for me, and I’m pretty sure it is for a lot of the other players. The shaking just starts when you turn off of Washington and get to the gate.”

Elder takes particular pride in qualifying for Augusta by winning a tournament, rather than pushing for some type of special invitation.

“If I really wanted to press it, I had a chance where I think I could have maybe gotten a little help with trying to come here and play at Augusta,” he said. “But just like when I was first asked about it: `Would you accept a special invitation to come to Augusta?’ I said no. The only way I wanted to come to Augusta was to earn my way. I wasn’t going to accept anything but that.

“So that’s what I did.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.