- Share via

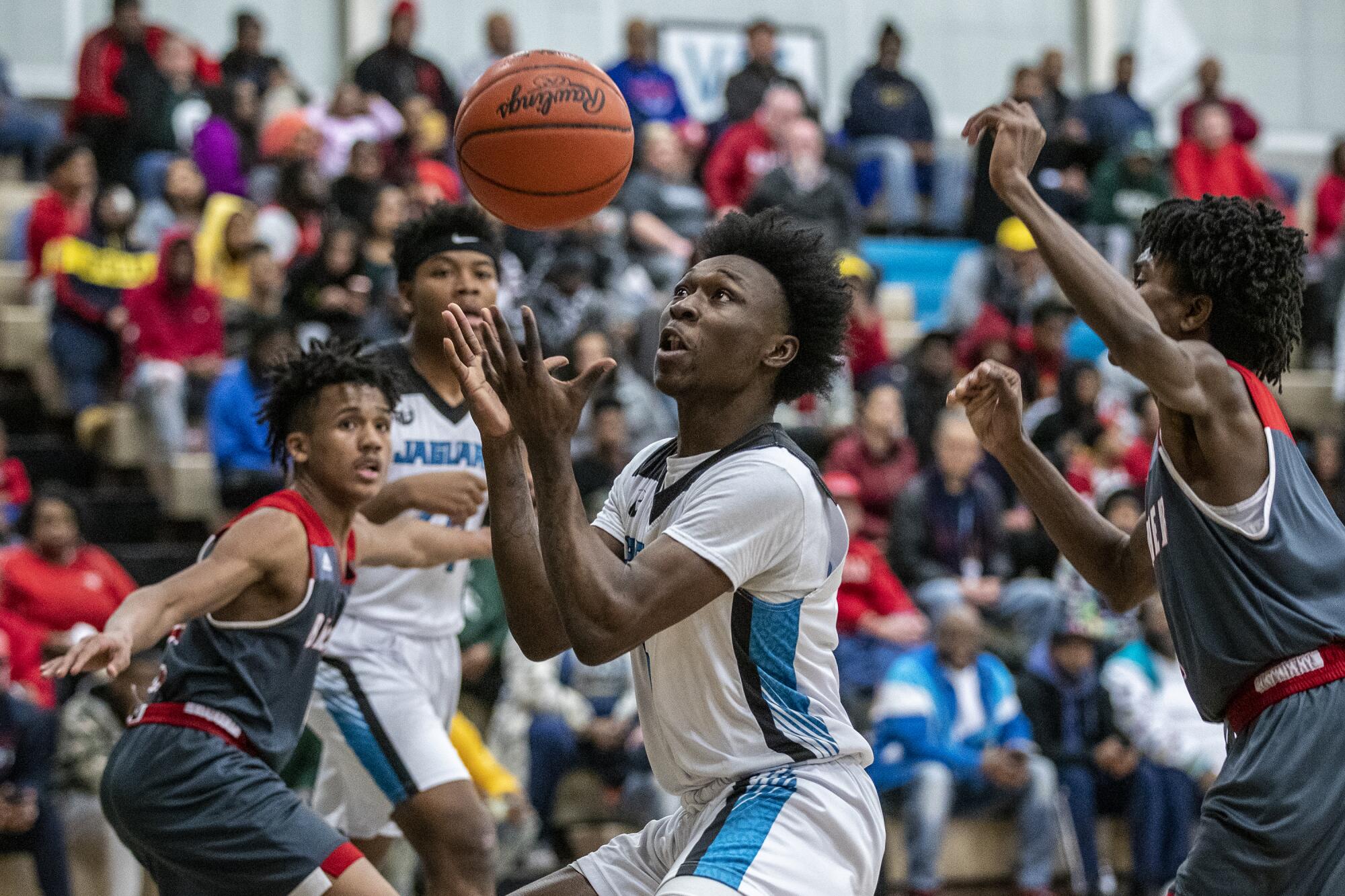

FLINT, Mich. — One by one, the boys slip on their jerseys. The new coach let them pick their numbers, seniors first, lending his players a tangible sense of ownership, acquired seamlessly through a transfer of black and teal polyester from hand to hand.

Over the last two basketball seasons, the Flint High Jaguars won a combined seven games, so this year’s opening night comes with no fanfare. But the one thing their coach wants them to understand before jogging onto the floor is that these moments belong to them and nobody else.

The vertical mirror hanging on the locker room wall shows a team readying for battle, earphones in, focus fortified. Of course, a reflection can distort reality, ever so slightly. They will learn the truth soon.

Outside, at the entrance to the Bendle High gymnasium, they’re handing out game programs. While the home Bendle Tigers roster is listed proudly, the adjacent space for the Flint Jaguars is blank. Just why is unclear, but the omission of the players’ names is yet another slight, another indignity, for a team and city used to both.

Number 35 steps in front of the mirror, getting one last measure of himself as his final year of high school ball begins. His name is Dekobe Lemon. He’s a sinewy point guard who only two months ago had decided he wasn’t going to play this season after the last coach left. The new guy — Flint’s fourth coach in four seasons — reeled him back in, telling Dekobe he would try to get him to a junior college for basketball.

- Share via

Prep basketball players in Flint, Mich., discuss the importance of the game in their lives and their perspective on the upcoming season.

In Flint, lofty promises often go unfulfilled. Yet here Dekobe stands on a Tuesday night in December with his city’s name across his chest one more time, revealing a freshly inked tattoo on his inner left forearm. Stairs rise, encircling a quote from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.:

Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.

For this to work, for Dekobe’s belief to pay off, the Jaguars need Number 11 to be the best version of himself. His name is Taevion Rushing. He’s a soft shooter with hard edges, a senior guard who has a star quality — with bouncy dreadlocks, pretty-boy pink sneakers and undeniable personal magnetism — but nothing to show for it through three years on varsity.

Some of the Jaguars remain leery of Tae. They think he was a big part of why last year’s team played so selfishly. After he quit midseason, chemistry improved. Could a couple of weeks of Demarkus Jackson’s running-heavy practices really have altered Tae’s DNA?

As Jackson gathers his eight eligible players, a hollowed-out hoops town’s leftovers, it is Tae who routinely responds affirmatively to the messaging, barked bitingly by a 29-year-old who speaks their language.

“Flint was not on nobody’s list,” Jackson says. “We a joke. We a joke to everybody.”

“Let’s make a statement,” Tae jumps in.

Flint has always done its talking through basketball, particularly after the shops shuttered and moved elsewhere. These Jaguars grew up with the stories — of a hard-working culture at General Motors, of a trio of young men from their neighborhoods who came together as the “Flintstones” to win a national basketball championship at Michigan State — but little of the community investment to mold them in the same blue-collar way.

Beyond the sporting cliche of making a statement, what would the Jaguars say? And to whom would they say it? They can look at the sparse crowd on the road team side tonight and know that Jackson is right — no one from Flint is thinking of them.

“Now it’s up to us,” Jackson says.

But the Jaguars come out flat. Tae scores the first nine points, keeping them in the game with Bendle, a small suburban school that traditionally would have been served up as red meat to Flint’s finest.

By halftime the Jags are trailing by eight, and on his way to the locker room Jackson overhears Bendle players talking about running Flint out of the gym.

“That’s how I know y’all soft as f—!” he tells his team. “This is ridiculous! We losing to Bendle! It’s about pride, man! Everybody already said Flint doesn’t care, and we proved them right. We practice one way and we come out here looking scared. Why? Because the crowd out here? Y’all want to be that same Flint team. That what it is?”

It only worsens.

“I should have transferred,” Tae says during a timeout, loud enough for teammates to hear.

Moments later, his mouth earns him a technical foul.

Bendle beats Flint 84-74.

The box score will say Tae, with 23 points, is the reason the Jaguars even had a chance. But did his outsized presence keep others from stepping into their roles?

“Man, where the f— is Tae at? I can’t see you!” Jackson says in the losing locker room.

Tae appears from behind a row of lockers, rejoining the Jags. But the team isn’t together, regardless of what the mirror shows.

“The statement we made,” Jackson says, “is we’re still dirt as hell.”A rusted pipeline

To enter the locker room of what is now Flint’s lone public high school, the Jaguars walk underneath a large wooden sign hammered into the wall above the double doors:

“Those Who Stay Will Be Champions.”

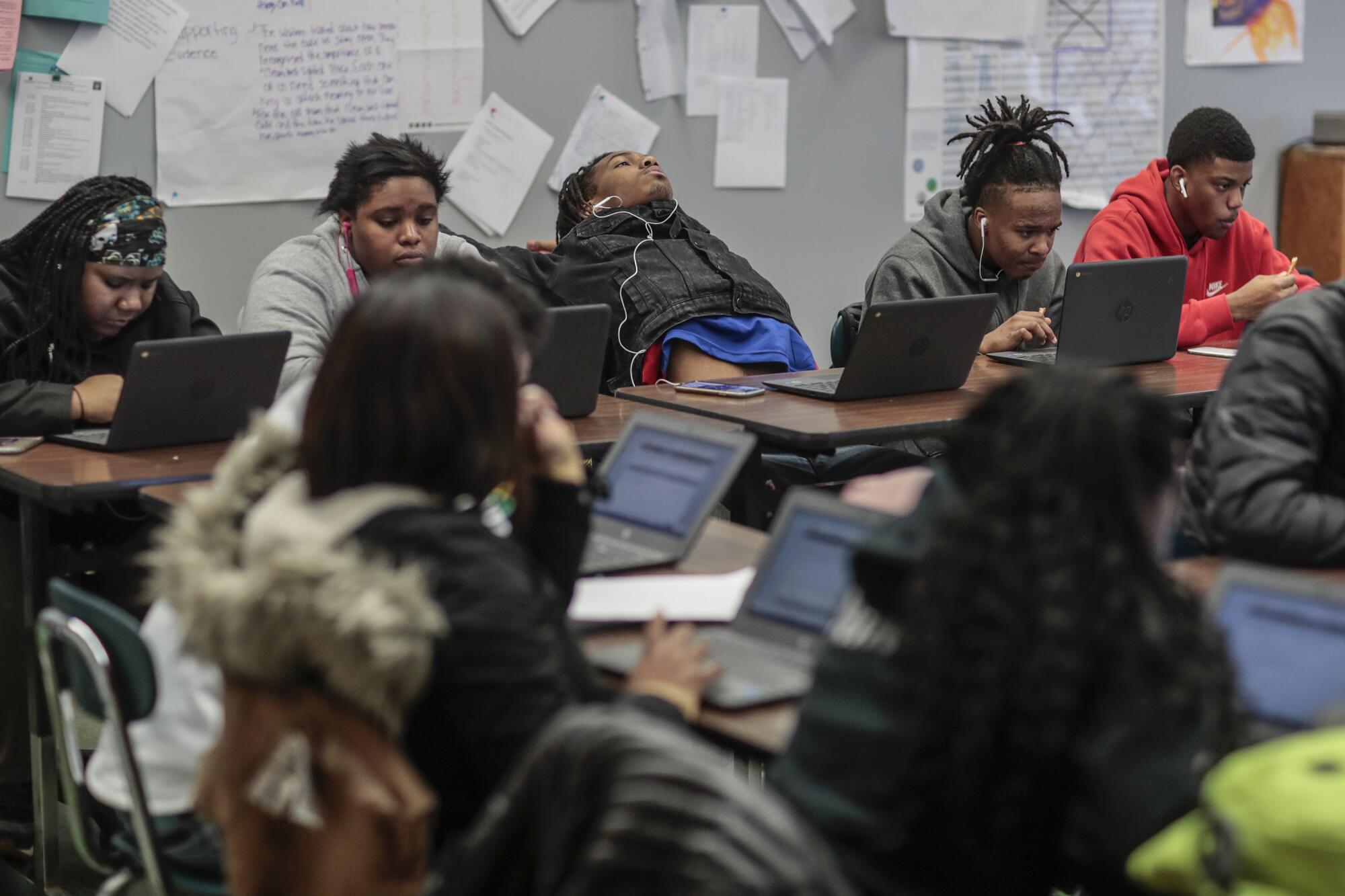

Hung back when this place was known as Flint Southwestern High, one of the city’s four powerhouse programs, the sign was meant to stir nostalgia and set expectations. Today, at Flint High, where the drinking fountains are still covered by black trash bags more than five years after the city’s water turned brown with lead, the mantra also serves as a reminder that so many lately have chosen to go.

Flint had once been a model for industrial cities, but as the auto industry went into decline, basketball players became Flint’s greatest export. GM began its long goodbye in the 1980s, right as the Flint public high schools were on a remarkable five-year run of winning Michigan’s Class A state title over Detroit schools.

Flint’s heartbeat was the ever-present dribbling of a basketball. The Flint Northwestern title team from 1984-85 featured Glen Rice, an NCAA champion at Michigan and NBA All-Star. No matter the year, the rosters of the four teams were stocked with future college players.

But, even before the water crisis, Flint schools’ pipeline to the next level began to rust. It wasn’t that the city didn’t have talent. At some point, a generation of kids had become convinced that they had to leave the city to be developed. For instance, the Lakers’ Kyle Kuzma is from Flint but was groomed in the suburb of Grand Blanc. The Nuggets’ Monte Morris starred one mile north of the city at Beecher, giving this week’s Western Conference Finals a genuine Flint flavor. Miles Bridges, of Michigan State and the Charlotte Hornets, played his freshman year at Flint Southwestern before leaving for prep school.

Charter schools began popping up in the late 1990s as GM exited and tax revenues for schools went with it. Then, the state began an initiative called “School of Choice,” which gave students the opportunity to attend any high school entering their freshman year, as long as they did not have behavioral blemishes.

For many families, that program has been a winning lotto ticket to a better life, creating a market for the poaching of Flint’s top eighth grade players. Beecher has won five Class C state titles since 2012 with a steady flow of Flint kids.

But in Flint there still seemed to be reason for hope, even if a basketball renaissance did not appear immediately on the horizon.

In 2019 the Jags’ coach was Napoleon Petteway, a Flint native who played professionally overseas and wanted to be the man to reestablish the tradition. Petteway talked of moving on from the past, stripping the Southwestern logos and colors from the gym walls.

He acknowledged the school could never be what it had once been, so why hold on? The Knights were gone, replaced by hungry Jaguars. He pressured the district to repaint the gym floors in black and teal. But, a month after work began, Petteway accepted the coaching job at a local charter school that would more than double his $3,900 stipend at Flint.

Soon after, DeAndre DeLeon, Flint’s most productive player from 2018-19, decided to transfer to Flushing, a rural suburb where his mother felt he could receive the education he deserves along with a chance to flourish athletically. Another potential Jaguar missed tryouts because he spent a month in jail after being charged with hitting a female classmate.

Now, the day after the Bendle loss, as Demarkus Jackson stands in front of those who did stay, asking for full buy-in, the kids can’t help but remember this irony about their new coach: As a kid, he did not stay in Flint either.

After playing his freshman year here at Southwestern in 2004-05, Jackson transferred to Hamady High, just north of town. While kids leave today to escape, he left because it was so competitive for playing time that he did not think he would get a chance to shine.

At Hamady, Jackson made all-state his senior year. Nearly a decade later, it’s not much of a jump to imagine him as a stocky point guard who put the dog in underdog.

His fundamental task, beyond simply winning games, is to teach them how to do it as a team.

“Y’all brothers,” Jackson tells them. “You gotta trust the next person. Tae, you especially!”

Tae sits casually on the top of a row of lockers, his legs dangling above his teammates, who slump on the bench below.

“We can’t down-talk nobody,” Jackson says. “I don’t even want to hear it, because nobody is out there just killing it.”

Before they hit the court, Jackson lets them in on something, although it’s not exactly a secret.

“It’s us against the world,” he says. “If you don’t believe me, I got a tattoo across my collarbone. It says ‘Me against the world.’ I don’t trust a soul except the people that with me. You’re either with me or against me.”

Two nights later, in the home opener, Flint blows out Atherton 78-46.Peeking into Tae’s world

Taevion Rushing was 12 years old when the water source for the city of Flint was silently switched from treated Detroit and Lake Huron water to the Flint River to save money. A lack of corrosion controls allowed lead to leach into the water. Tae’s older sister Tyra broke out in hives all over her body. Another older sister took it as a sign and moved out of town for three years.

When Tae was 14, President Obama came to town. Mid-speech, as a political stunt, he coughed, asked for a glass of water (it was filtered) and drank from it.

“I don’t want anybody to start thinking that somehow all the kids in Flint are going to have problems for the rest of their lives because that’s not true,” President Obama said. “I don’t want that stigma to be established in the minds of kids.”

Tomorrow, Tae turns 18.

As a light snow falls outside on this January night, Tae’s mother, Verona Johnson, and her seven children gather to discuss the city that reared them.

All the Rushings went to Flint high schools. The older ones remember a time when two Flint teams playing each other in basketball meant sold-out gyms and students jockeying in line for tickets during lunch breaks.

“Back when it was four different schools, it was more like rivalries,” Tyra says, “and now we don’t have nothing.”

“Almost every other day, I check his page to make sure he’s not up to bullcrap.”

— Demarkus Jackson, Flint basketball coach, on Taevion Rushing

Listening to her, it would come as quite the surprise that Tae and the Jaguars have run off five straight wins since Bendle, setting up an intriguing game against rival Hamady tomorrow night.

Thanks to the winning, this year’s team is building a better vibe. Dekobe even started a group texting thread for the Jags, teeming with juvenile jokes and the latest trash talk from opponents on social media. Beating Hamady would be quite the birthday present for Tae, who’s finally having fun playing the game he loves.

Before this season, Tae wasn’t thinking about playing in college. Demarkus Jackson quickly changed that.

Tae’s family supports him, but they’re detached from the details that can get him out of here. His three older sisters went to college, yet they’re only starting to talk about it with Tae, who’s five months from graduation.

“I want him to go away, just to see something different,” Verona says.

No matter where Tae goes at any given moment, all he sees is his iPhone. Later in the night, he’s in a booth at Applebee’s with fellow Jaguar Julian Gardner, but his brown eyes are glued to the screen in front of him.

By day’s end, Tae will have racked up more than 11 hours of screen time. He says he’s averaging 360 notifications a day.

From head to toe, he’s a picture of a generation’s well-crafted narcissism, his dreads pinned up neatly in a bun, his footwear always fresh. Tae says his family often pools its money to make sure he’s outfitted. Tae begins a Facebook Live session, which allows friends to watch him while he waits for his free birthday brownie.

What Tae doesn’t know, as he yucks it up with Gardner, is that his coach is quietly watching him from his Facebook account.

“Almost every other day, I check his page to make sure he’s not up to bullcrap,” Jackson says later.

Jackson didn’t take this job to win some humanitarian award for working with disadvantaged kids. He was let go from his first coaching job, at tiny Madison Academy. He decided to apply for the open Flint position in October because his mother felt he could connect with these kids as a younger coach.

He wants to build his coaching resume, while working a 40-hour week at a climate control systems firm and attending graduate school for business at Ferris State and helping his fiancee plan their wedding.

But, as a son of Flint who overcame a strained relationship with his father to find success, he does have some life perspective to offer this group, a roster full of mama’s boys. In Tae’s case, his dad moved to Texas a few years ago, and with his mom always working, he’s often on his own.

One thing Jackson likes about the scene he saw at Applebee’s? Tae was with Gardner, a Jaguar, not his normal group of siblings or cousins.

Because if the Jags are going to keep rolling — and win some games that would get Flint’s attention — then Tae is going to have to start thinking of his teammates like they’re his family.Birthday popcorn

They call this a “city game,” a rarity these days in Flint. Hamady, just a few blocks north of Tae’s house, accepts a lot of kids who would have gone to Northern or Northwestern, and most of the Hamady staff is made up of former Flint teachers. Hamady has problems, sure, but they’re not Flint’s.

Jackson is a Hamady alum, but the school did not hire him a year ago for its open coaching position. He’s been gnawing on that since, but he has to put it aside. This one’s for the Jags more than him.

“1-2-3 Flint! 4-5-6 family!” the team responds, breaking the huddle.

Off the tip, Hamady takes a prompt 8-0 lead.

So far, Tae’s 18th birthday party could not be any more of a dud. He picks up a couple of early fouls and finds the bench. Flint soon has 17 fouls to Hamady’s six, so the Jags should feel pretty good trailing just 29-25 at halftime.

“Listen, the refs cheating, we all know that,” Jackson says. “But guess what? The refs cheated at Bendle too. We gonna use the same excuse and lose again?”

Next, he preaches a message of accountability. His kids are consistently looking for someone else to blame.

“There’s a certain way that you tell people stuff,” he says. “Y’all out there arguing with each other. Now you’re looking weak. There’s a difference in telling your teammate something and hollering at your teammate. I already told y’all that! We’re not frustrated! We in the game!

“Play Flint basketball!”

In the third quarter, the Jaguars lock in, but Jackson is seething because the refs won’t get out of their way. He loses patience and gets a technical foul.

Moments later, a Dekobe three gives Flint its first lead, at 41-40. The Jaguars go on a 24-4 run, sending the Hamady fans into the cold night.

With the game in hand, Tae can relax. His young nephew brings him a bag of popcorn, and Tae relishes each birthday bite from the bench.

From a relieved visiting locker room, Jackson gives the Jaguars a pointed final order. Even after a convincing win, and with a 6-1 record, appearances matter.

“We all leaving out of here together,” he says.

But Jackson doesn’t enforce it. The kids disperse at their own leisure. Tae walks out with Dekobe, talking about a girl he noticed in the bleachers.A rivalry that cuts deep

For Dekobe, senior year has been a revelation. The Jags are 13-2, and Dekobe recently was nominated in an online vote for the Flint area player of the week. He didn’t win, but it at least felt like somebody noticed him.

Now, on a February afternoon that’s fading fast, he’s in the chair at Courtside Cuts, a Flint barbershop where basketball chatter is always welcome. Tomorrow, they’ll play Beecher High, the top-ranked team in the state. The shop’s owner, Omar Harris, is a Beecher guy.

Harris even had a mural painted here that declares “Flint made me, Beecher raised me.” Courtside Cuts isn’t exactly enemy territory, but it represents the city’s complicated view of itself.

Tae and three other Jaguars join Dekobe. They find out that Harris and Dekobe’s older brother, DeAnthony, have made a bet on Flint-Beecher:

If Beecher wins by 20 or more, DeAnthony, who recently started his own apparel company, will make new shirts for Harris’ shop for free. If Beecher wins by 19 or fewer, Harris will buy the shirts.

The Jags are rightfully offended.

“Y’all win,” Harris says, “I’ll buy all five of y’all Jordans.”

All they can do is laugh and look at one another, dumbfounded.

“I want Timbs,” Tae says.

Truth be told, Harris thinks Beecher will win by 30.

“Why do you think that?” Tae asks earnestly.

“I was looking at who y’all was playing and stuff,” Harris says.

This season is Flint’s first as an independent. The school left the historic Saginaw Valley League because it could no longer compete. Flint’s schedule is undeniably lighter, packed with schools it should beat, which is why the Beecher game means so much — and also why nobody is taking the Jaguars seriously.

“The third quarter come,” Harris says, “you look up and go, ‘How the hell did we get down 30?’ ”

The Flint players shake their heads. They’ve lost two games all year and this is what they’ve got to listen to, in the heart of their own city?

Harris says he’s going to be at the Flint gym with his popcorn ready.

“He gonna be sitting there with his popcorn, sad,” Tae says.Playing the cool school

Beecher coach Mike Williams has become something of a local legend the last decade. Thanks to the “School of Choice” policy, he’s been able to build up his program, and no team has benefited more from Flint’s demise than Beecher, which sits a mile north in Mount Morris Township.

How did Beecher become one of the top programs in the state facing many of the same societal issues? Simple. The school found a good coach who wanted to stay. Can Demarkus Jackson become that for Flint? He won’t be able to do it if Williams keeps scooping up the best players.

It’s a delicate dance for Williams. The way he sees it, a premier talent staying in Flint and bringing the pride back could save this school from closing like the other three.

“That’s how powerful basketball is around here,” Williams says.

Still, it is Williams’ job to hang a sixth state title banner at Beecher.

With the Flint-Beecher tipoff minutes away, it comes as no surprise to see Williams greeting a 6-foot-7 Flint eighth-grader, Aijalon Williams, and bringing him close for an embrace.

Aijalon and Keenan Reese II, the best eighth-grader in the city with his pick of schools, take their seats on the Flint side of the bleachers for now.

Williams has had his eye on these two and wants them at Beecher. In the old days, the idea of scouting junior high practices would have been laughable.

“I could ride down any street on the north side of Flint or in Beecher and go find a guard,” Williams says. “You can’t do that anymore.”

Keenan’s father, Keenan Sr., was raised on Flint’s vibrant north side, where you either wanted to be Northwestern Wildcat or a Northern Viking. Now the only option in the district is down at Flint High, which, given the old neighborhood allegiances, feels all wrong. Then again, he admits, he probably wouldn’t send Keenan to any Flint high school.

In 1960, nearly 200,000 people lived in Flint, which then felt like the embodiment of the American dream. Today, just under 100,000 call the city home. Updated census estimates say the population is about 54% Black and 40% white. The median owner-occupied house is valued around $29,000.

“They say they love basketball, but some people just like it. I wish he would have taken it seriously. He could have gone to a high [Division I school] or something.”

— Jalen Terry, Beecher High star, on Taevion Rushing

“Where I grew up, there’s probably two houses [standing] on my whole block,” Reese Sr. says. “The elementary I went to, it’s gone. It’s pretty much like a ghost town over there.”

This year’s Beecher star, a high-flying senior point guard named Jalen Terry, will next play at Oregon. Jalen grew up in Flint, on the same summer youth team as Tae.

“He could always shoot, but he never really took it seriously,” Jalen recalls of Tae. “Every kid has basketball dreams, but not many of them really want to do it. They say they love basketball, but some people just like it. I wish he would have taken it seriously. He could have gone to a high [Division I school] or something.”

In eighth grade, Terry’s parents decided Coach Mike could help their son reach his potential at Beecher. Nobody stepped in to guide Tae, who wasn’t the type to do it himself.

“If I had left, I’d have gotten way better,” Tae admits.

Still, tonight, he has plenty to play for. He swishes his first shot, a three, as Omar Harris, the betting barber, looks on from the front row, wearing his Beecher red.

Despite the referees whistling Flint for the first 12 fouls of the game, the Jags are hanging in. Beecher leads 30-29 at halftime.

“It’s 0-0!” Jackson says.

But before long, just as the barber predicted, Flint trails 49-33.

It already feels over, and that’s before Beecher’s Earnest Sanders, who will play football at Kentucky, throws down a few dunks that bring the rowdy Beecher fans to their feet.

“You guys quit,” a man says as he walks by the Flint bench.

Eighth-grade recruits Aijalon Williams and Keenan Reese II have seen enough of Flint too. They’ll decide to attend other area high schools.

The Jaguars can’t even find the energy to help Dekobe’s brother win his side of the bet. Beecher rolls to a 76-53 victory.

What happened? Jackson asks his players, and the Jags begin talking over one another, proving their coach’s point.

“No communication,” Jackson offers in a quiet locker room. “We still arguing on the floor, every single time.”

Says D’Angelo Mays, “It be the same ones, not gonna lie. Tae …”

“I ain’t argue, bro!” Tae responds.

“Everyone be arguing!” D’Angelo says.

“We 13-3, and we weak as hell,” Jackson says.

As the players pack up, Jackson’s head is down. He looks like he took a 22-point second-half beating all by himself. It’s Wednesday night, and he tells the Jaguars he’ll see them Saturday. They could all use some space.

The coach is the last one left in the locker room. A visitor asks him if he heard the man say that his players quit.

“Yeah, that was my dad.”

Was he right?

“They quit,” he says. “But there’s a certain place to say stuff, and that wasn’t the time to do it.”‘Like a hero’

March is here.

The first game of the district playoffs will be against Kearsley, a nearby suburban school that beat them by 24 points last year in this same opening round.

The Jags are down four players — one quit, two had academic trouble and another overslept his nap and showed up at halftime. Somehow, though, the score is tied at 52 in the fourth quarter.

Tae scores the next seven points, a three-possession exhale. Flint wins 67-59, giving the seniors their first playoff win.

Tae’s 31 points — and that flourish at the end — draw the admiration of a little girl in the stands. She wants to meet him.

“I feel like a hero!” he says.

Hours later, on Flint’s ABC affiliate, the local news anchor mentions Tae’s points in the nightly roundup. It’s an exciting moment for most who know him — but not all.

When one of Tae’s teachers hears his name on the news, she does a double take.

Tae had not been at school this morning. According to the rules, that meant he could not participate in extracurricular activities. She decides to raise the issue with school officials.

“It’s rough on someone like me, in my 23rd year in this building,” says the teacher, who asked to remain anonymous due to fear of retribution. “We’re not teaching them. They’re not learning the real life consequences. With the water crisis, much of what our community has done is given people excuses for poor behavior. And then we wonder why they’re not being successful.”

This teacher has been trying to get through to Tae, who is in real danger of not graduating. But she can’t teach him to care.

The teacher is happy the Jaguars are winning.

“It would be nice to have our school be organized enough to grab onto their success,” she says. “That would be phenomenal. But everybody is so overburdened. School spirit has taken a huge hit.”

Flint is 17-4, winning more games than it had combined in the three prior years, but the school hasn’t organized one pep rally to honor the kids.A familiar toughness

The day of the game against suburban power Davison, Demarkus Jackson is tiptoeing the Tae tightrope as he has all season.

Jackson says he did not know that Tae had been absent before the Kearsley game. He is angry but not surprised. The moment he took the Flint job, he had a decision to make about the best player, and Jackson chose to give Tae a real chance, to let him play through some mistakes, on and off the court, unlike past coaches.

He hadn’t met Tae, but he felt like he already knew him through his older cousins. Tae was the latest in a long line who squandered their gifts. Cousin Rashad was the top player in the city but flamed out in junior college because he couldn’t stay out of trouble. Cousin Kaylin was the best of them all but never made it to college.

“I really think he could have been in the NBA,” Jackson says, “but the streets took him.”

These were the guys Tae grew up idolizing. Jackson wanted to offer him a better aspiration, and the experiment has mostly worked.

“I don’t know what Tae wants,” Jackson says. “Sometimes, he a leader. Sometimes, he a follower. Never know what Tae you’re gonna get.

“We talk about the future all the time, but I’m not sure if it’s him talking just to talk or if this is how he really feels.”

“Flint honestly don’t wanna see Flint succeed either, sad to say. I know a lot of people be at the games that’s really there to see us lose, and then we win, they come up to me like, ‘Good job,’ but that’s not really genuine.”

— Flint coach Demarkus Jackson

Whether Tae graduates, whether he plays in college, that’s up to him. If he doesn’t, Jackson still got 17 wins out of it. The complaint by the teacher is resolved when Tae produces a letter from his mother explaining he was absent because he had to take care of his little sister. Now Jackson can go for 18 wins.

Davison won the state football championship in the fall. These Cardinal know much more about what it takes to win big games than the Jaguars.

“We ain’t been here before!” Jackson says before tip. “Let’s make history!”

Flint flies from the start. The Jaguars get on top with their full-court pressure defense, learning early that Davison doesn’t have the mental stamina to keep up.

Before long, the Davison fans are the ones yelling at the refs, booing and stomping their feet in protest. Nobody in the host gym here in Grand Blanc — a Flint suburb which fittingly translates to “Big White” — can believe it: Flint has the tougher team tonight.

“This reminds me of the old Flint teams,” says a woman in the stands.

Flint 74, Davison 58.

The Jags are going to the district championship.

Once in the locker room, they mob one another, grabbing the guy next to them and jumping in unison. Their screams bounce off the white brick walls, and, for these precious seconds, the Flint Jaguars know what it is to become one.

“We here!” they yell. “We here!”

“We got a championship Friday,” Jackson says, refocusing his team. “If we play like we supposed to play, nobody going to beat us! I told y’all. Two down, six more to go.”

“Six more!” Tae says.

“Six more!” Dekobe repeats.

They form a huddle.

“1-2-3 Flint! 4-5-6 family!”

Then the Jaguars roar again.Feeling ‘fake love’

The next day, Demarkus Jackson eats lunch at a sports bar while he waits for the news. The Flint school board is meeting about this new coronavirus that just postponed the NBA season.

The decision doesn’t need to be official for Jackson to know deep down the 2019-20 Jaguars won’t suit up again.

Still, after last night’s win, Jackson can see the big picture.

“Looking at the kids after the game yesterday, I know I did something,” he says. “That was something to be proud of. They basically felt like they won a championship already. You were in there. That was the first time they did that. All year, we never got that excited about winning a game.”

Did anybody else notice, though? Jackson bristles at the Flint Journal giving his team only a blurb.

“They waiting for us to lose to Grand Blanc so they can say, ‘Well, we knew they wasn’t anything,’ ” Jackson says.

“Flint honestly don’t wanna see Flint succeed either, sad to say. I know a lot of people be at the games that’s really there to see us lose, and then we win, they come up to me like, ‘Good job,’ but that’s not really genuine.”

Jackson vows that he will be the coach who sticks around Flint — within reason. He says he would leave only for a job with a college program, his long-term goal with his 30th birthday two weeks away.

In a few hours, his athletic director will tell him that the playoffs are postponed.

At school, word circulates. The Jaguars are hopeful the playoffs won’t be canceled, but they understand their season may be over.

“It’s a lot of fake love in Flint,” senior Onquay Clemons says. “Now that we’re winning, they’re trying to support us, but we don’t need that type of support. Because where was y’all the years before that? Coach tell us every game, it’s us against the world. So it’s really our brothers, it’s all we got. End of the day, people really want to see us fail.”

Dekobe’s phone has been buzzing all day with Grand Blanc players telling him they were going to make this his last game. Turned out, the virus would prove them wrong. Davison would be the Jaguars’ finale.

Dekobe, who began the year assuming he would join the Air Force after graduation, will commit in the summer to play junior college ball at Olive-Harvey in Chicago.

Dekobe chose to go in blind with Jackson and the Jags. Now, he can see the whole staircase.

“Hard work really do pay off,” Dekobe says.

Where’s Tae? He’s always an iPhone message away. He says he’s with his cousins.

He tells you to meet them at an outdoor court for some pickup basketball. Soon, a tan Chevy Suburban barrels into the parking lot and onto the grass, creating streaks of mud in the public park. Tae’s cousin and best friend, Kyren, spins the SUV in circles, the wheels slipping and sliding until Tae hops out the passenger side, laughing.

“If this is the last game, I’m gonna be sad, man,” he says. “We was supposed to beat Grand Blanc and go all the way.”

On a night he should have been practicing for the district title game, the best high-school guard left in Flint is playing for fun, wearing Crocs instead of sneakers, the braids of his hair flying wildly in the cold, lake-swept winds that could take him anywhere.

In months to come, Tae will graduate and spend the summer going back and forth about which junior college to attend. Looking at his Flint career in sum, he did not win the big game, did not become a Division I recruit, did not fulfill Flint’s destiny of old. So what was gained?

“I got close with my teammates,” he says. “I like this season the best because we are a team.”

In the end, they never achieved perfect harmony. The Flint Jaguars bickered as much as they bonded, but they trudged through the valleys of a long Michigan winter to reach a peak. Whether anybody saw it or not, they will always have the memory of those hugs and those screams from that jubilant locker room in Grand Blanc, where the mirror now said that anything was possible for a bunch of kids from Flint.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.