Memory of young baseball fan killed in school shooting lives on in 14 MLB ballparks

- Share via

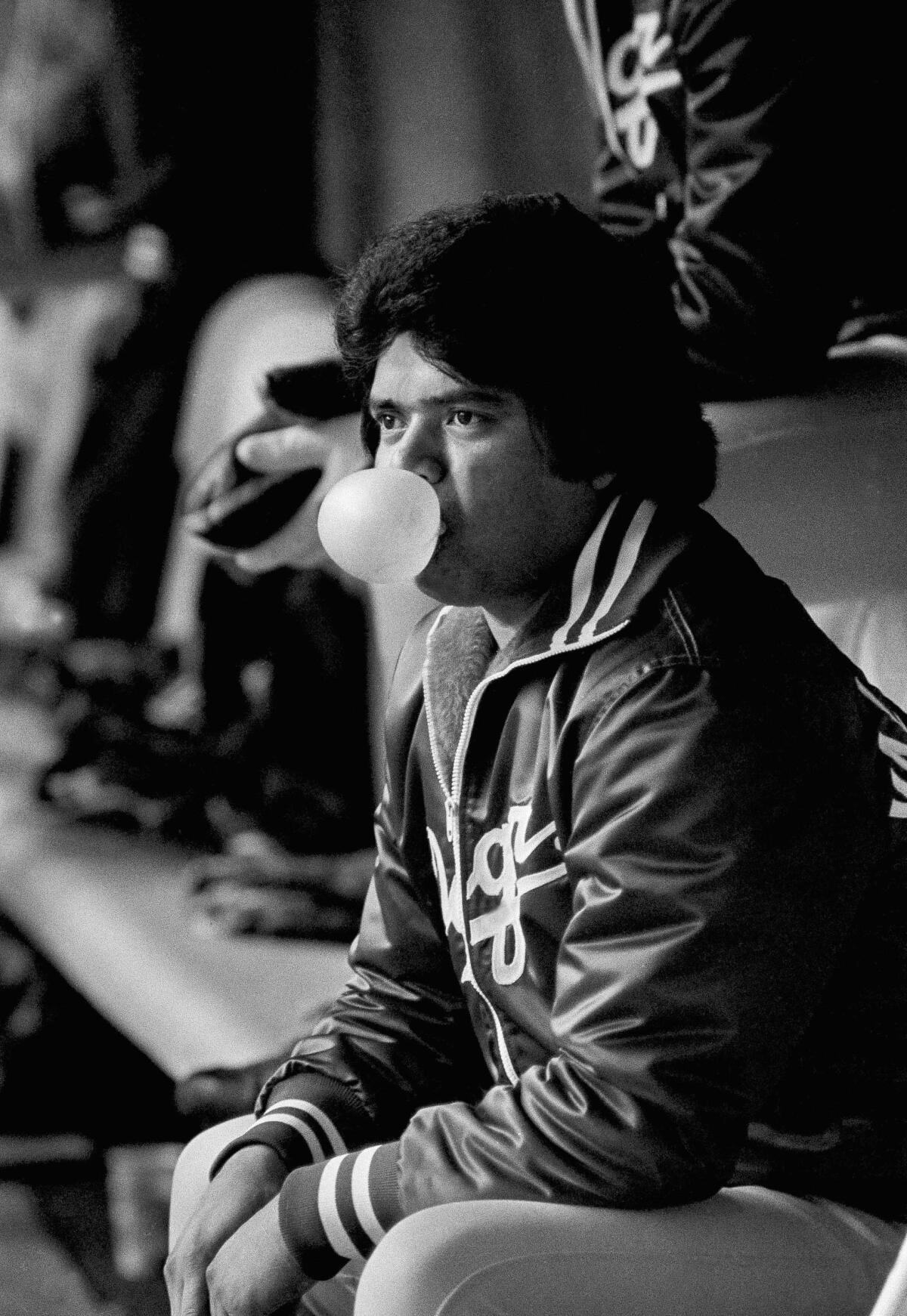

Joaquin Oliver occupies an aisle seat for every game at Dodger Stadium, seven rows up, in Section 150 of the loge level.

The boy sits there by himself, no friends or family around him. He is a cutout, of course. If this had been a better year, there would be living, breathing human beings in the stands.

If 2018 had been a better year, Oliver might have been one of them.

He and his father Manny loved to take baseball road trips. They would return to their Florida home with memories of the majesty of Yankee Stadium, the friendly confines of Wrigley Field, the pleasantly edible hot dogs at Fenway Park.

Joaquin was one of 14 students murdered two years ago at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High in Parkland, Fla. He was 17. He was shot four times and left to die.

“I will never know if my kid suffered pain during those moments,” Manny Oliver said.

Alex Wood said the main reason he re-signed with the Dodgers was to help the team try to win a World Series. He’ll be doing that out of the bullpen.

Joaquin is on his another baseball road trip this summer. His cutout appears in 14 major league ballparks, including the ones in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Oakland.

The cutouts help Manny Oliver raise the profile of Change the Ref, an advocacy group he launched to get gun laws changed and, if not, to get lawmakers changed. In the two years since Parkland, he said, there have been 83 school shootings and no significant revisions to federal gun laws.

He is baffled and outraged at the baseline for discussions about school safety. Why do we debate armed guards at school, or metal detectors, or active shooter drills? Why do we assume school shootings are inevitable, rather than work to limit guns of mass destruction?

“There is one victim in my house, and his name is Joaquin Oliver. The others are survivors,” Manny Oliver said. “We need to fight for him.”

That, he says, is why he will not cry when the Joaquin Oliver cutouts arrive at the family home after the season, when he will come face to face with more than a dozen faces of his late son.

“He was not only my son, but my best friend,” Manny Oliver said. “The fact that now we’re bringing him to the ballparks, in some way, makes me feel happy.”

In the two years since his son died, Manny Oliver said, he has not gone to a ballgame.

“There are things that are so connected to the loved one that you lost that you feel afraid to do alone,” he said. “I don’t have a baseball partner any more.”Retire No. 34 already

Let us celebrate the Philadelphia Phillies. The team this week retired the number of Dick Allen, in the process abandoning its policy that a number could not be retired if the player did not make the Hall of Fame.

“The most important job I think I have in this position is to protect the legacy of the people whose jerseys are retired,” Phillies owner John Middleton said on a videoconference. “If you’re not going to insist that they be in the Hall of Fame, you need to make a compelling case that they are Hall of Fame-worthy.”

Allen had a distinguished career, and the Phillies hope that a veterans’ committee someday elects him to the Hall. Middleton even noted that Allen rated the same as Willie Mays in one advanced metric (adjusted OPS+). In elections conducted by the Baseball Writers Assn. of America, Allen never got more than 18.9% of the vote.

“To me, I think it’s wrong to say we’re only going to allow people’s jerseys to be retired if a bunch of writers across the country vote them into the Hall of Fame,” Middleton said.

“This is a Philadelphia honor. If you rely on people who are voting from California and Oregon and Missouri and every other such place, I don’t think that’s fair.”

Fernando Valenzuela never got more than 6.2% of the vote from the BBWAA, but his place in Dodgers history is secure, his transformation of a fan base still evident four decades later. The Dodgers, like the Phillies, have resisted retiring numbers of players who did not make the Hall of Fame.

The Phillies wisely have reconsidered. The Dodgers should too, and should retire No. 34 next year.Thanks for the memories

Ron Swoboda asked New York Mets teammate Tom Seaver a couple years ago about an on-field conversation during the 1969 World Series. Seaver’s dementia had so taken hold that he said he had no memory of the conversation.

Seaver, one of the game’s greatest pitchers, died this week at 75.

“I realized this dementia thing had gotten in there like a thief and had stolen these memories from him,” Swoboda said on a videoconference. “For me, those memories are gold, and the idea that something could worm their way in and steal those and they’re gone was devastating, tragic. Tom was losing that stuff and that dementia was going to win.”

Seaver died of complications from dementia and the novel coronavirus.

“I wondered,” Swoboda said, “if COVID-19 might have spared him that long, slow walk into nothingness that dementia represents.”Silver anniversary

Cal Ripken sets consecutive games played mark.

Cal Ripken set one of baseball’s most treasured records 25 years ago Sunday, when he played in his 2,131st consecutive game. Ripken and his streak were so beloved in Baltimore that, when owners planned to start the 1995 season with replacements for the striking major leaguers, Orioles owner Peter Angelos vowed to protect Ripken’s streak by refusing to field a team.

The Angels were the opponents on the record-breaking day. In the fifth inning, when the game became official and Ripken took a victory lap around the field to shake fans’ hands, Angels right fielder Tim Salmon thought about jogging over and getting a handshake of his own. He didn’t — but, after he doubled later in the game, he enjoyed a nice chat with Ripken at second base while the Orioles made a pitching change.

“I felt like I was standing next to the president or something,” Salmon said. “I knew every eye in the building was on us.”

Salmon said he still has a photograph of that moment, and three commemorative baseballs. His wife still has her ticket stub.

Times staff writer Mike DiGiovanna contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.