Column: Mabel Fairbanks’ story deserves to be told. Two of her protégés are working to do so

- Share via

Racism deprived Mabel Fairbanks the chance to become a figure skating champion in the 1930s, an era when she saw signs at rinks shamelessly declare, “Colored Trade Is Not Solicited.” Because of that, she made sure, as a coach, that her Black students became members of prestigious figure skating clubs and enjoyed the privileges and support she didn’t have.

Fairbanks, who was of Black and Seminole heritage, wasn’t allowed to compete for a berth on the U.S. team for the Olympics and was relegated to minor roles when she performed in ice shows. Because of that, she made sure the Black skaters she coached had chances to excel and triumph — and many did.

Fairbanks’ remarkable story has been told in bits and pieces before and after she died at 85 in 2001. Her resting place at Hollywood Forever Cemetery is marked by a plaque etched with a pair of figure skates and the words “Skatingly Yours,” the phrase she’d add when she signed autographs.

A generation later, the life of the first Black person elected to the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame deserves a comprehensive telling. Two of her acolytes are working to bring back to light the woman who loved frivolously bright costumes and gold-toned skates but had a will as sharp as her blades when it came to creating opportunities for her students.

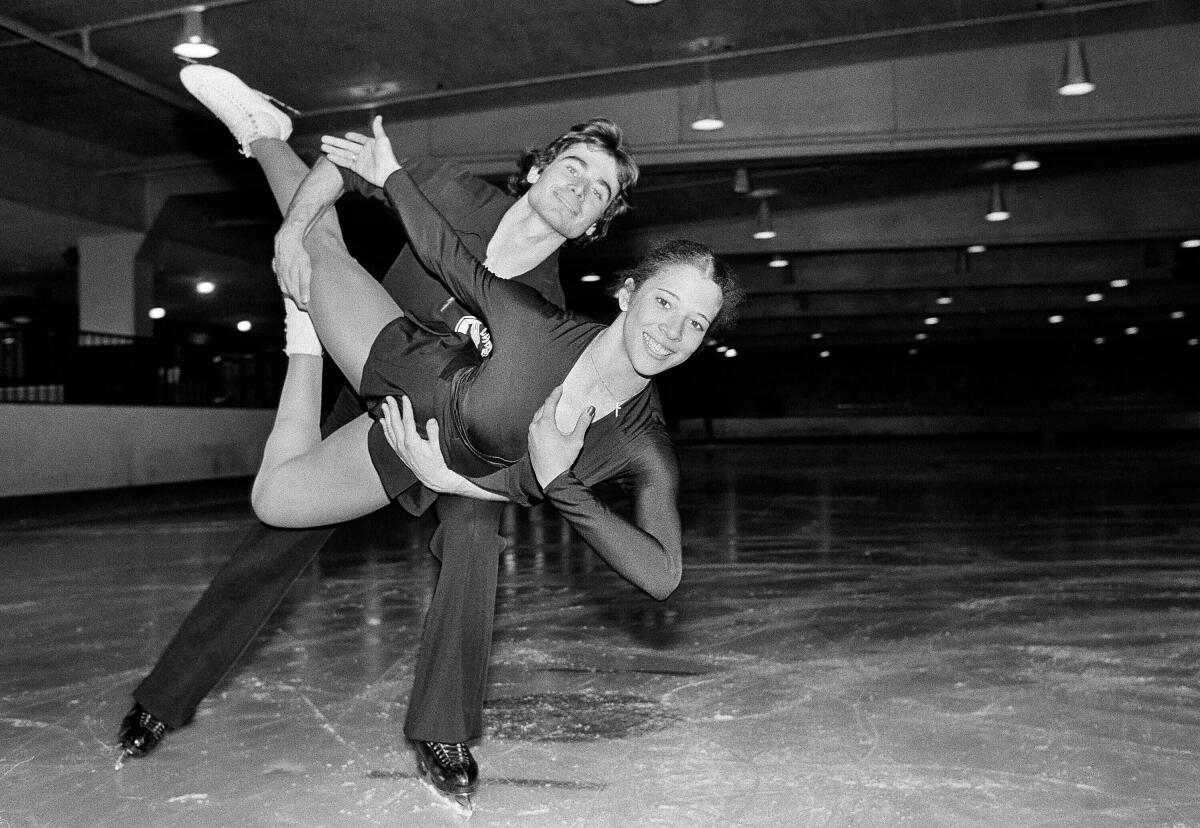

A project envisioned as a serialized TV biography of Fairbanks is in the works. It’s being nurtured by Tai Babilonia, who took a first step toward sharing the 1979 world pairs championship when Fairbanks told her to hold the hand of a boy named Randy Gardner at the Culver City rink in 1968, and by Atoy Wilson, who in 1965 became the first Black skater to compete at the U.S. championships. A year later, Wilson became the first Black skater to win a U.S. title when he earned the novice championship.

“Treatments have been done and have been seen by some prominent people,” Wilson said in a phone interview. “Her story is getting into the right hands that can get this going.”

Wilson, the executor of Fairbanks’ estate, asked Babilonia to comb through their mentor’s newspaper clippings, programs and diaries. “She was a little bit of a hoarder,” Babilonia said with a laugh. The memorabilia will enhance the story for those who knew Fairbanks and her accomplishments; those who aren’t familiar with her can learn how she changed the sport forever and for better.

Wilson and Babilonia hope that, eventually, the National Museum of African American History and Culture will display some items. “She fought for us. She broke down those doors for us,” Babilonia said. “So now we fight for her, and we are fighting hard.”

Fairbanks helped Wilson and Richard Ewell, another Los Angeles-area standout, become the first Black skaters to represent local clubs: In 1965 Ewell was accepted into the All Year Figure Skating Club and Wilson was admitted to the L.A. Figure Skating Club. Ewell also became the first Black skater to win U.S. singles and pairs titles when he won the 1970 junior men’s championship and teamed with Michelle McCladdie — who also is Black — for the junior pairs title in 1972.

Among other skaters influenced by Fairbanks are Debi Thomas, a two-time U.S. champion who won the 1986 world title and 1988 Olympic bronze medal, and 1992 Olympic gold medalist Kristi Yamaguchi. Fairbanks worked with her when Yamaguchi competed in pairs alongside Rudy Galindo. “There would not be an Atoy Wilson or a Tai or Richard Ewell or Debi Thomas or any of those people without her tenacity, her aggressive, diplomatic, way of being determined to open these doors for us because they were not open for her,” Wilson said. “She was a visionary.”

Olympic figure skater Mirai Nagasu, who grew up in her parents’ restaurant in Arcadia, is determined not to let the coronavirus close the family business.

Fairbanks was born in Florida in 1915. Her mother died when she was young and she moved to New York to live with a brother. She became homeless when her brother’s wife kicked her out but found a job as a baby-sitter for an affluent family.

From the moment she looked out of that family’s living room window and saw skaters gliding on the ice in Central Park, she was entranced. She bought a pair of skates for $1 at a pawn shop. Initially no one would teach her, so she picked up moves by eavesdropping on white skaters’ lessons. Her talent impressed famed skater-turned-coach Maribel Vinson Owen, who refined her technique.

Opportunities for Fairbanks to skate were few, mostly in skating shows staged in nightclubs. And she wasn’t allowed to do her best jumps and spins because “none of the white skaters wanted to be outshone by someone black,” she told The Times in a 1998 interview. Eventually she moved to Los Angeles, where she taught aspiring champions and anyone who simply loved to skate. Her house in Laurel Canyon became Babilonia’s second home.

“We could have been her best student or her beginning student; she treated us the same,” Babilonia said. “And we were all different colors. That was the beauty of Mabel, also. Culver Ice arena was like a rainbow-filled ice arena. We were her kids. We were the kids that she didn’t have.”

Fairbanks changed Babilonia’s life by pairing her with Gardner to perform in a club show. They won five consecutive U.S. titles and were favored for gold at the 1980 Olympics before Gardner aggravated a groin injury and they had to withdraw from the competition.

“I didn’t even know what pair skating was,” Babilonia recalled, “and she simply said, ‘Hold his hand and skate around the rink.’ I was 8 years old — Randy had cooties and he was a much better skater than I was and he was outgoing and I was shy. What was she thinking? That’s the one question I never asked her. What was she thinking when she put us together? But I thank her every night before I go to bed for creating Tai and Randy.”

The television project about Fairbanks was underway before George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis in May triggered anti-racism protests around the country, but the elevated public discussion of racial injustice makes her story especially relevant.

“It’s understanding that, from abject poverty in the late ’20s in Jacksonville, Fla., the story line is basically, ‘You little black girl, you’re not going to be anything other than maybe a housemaid or if you’re lucky a schoolteacher in a black school, in that ghetto,’” Wilson said.

The life lessons Wilson and Babilonia gained from working with Fairbanks proved as valuable as her guidance on how to pull off a spin or land a tricky jump. They’re applying her indomitable will to their quest to tell her story.

“We’re working hard,” Babilonia said, “and Mabel is right by our side, pushing us.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.