Column: Boxing industry tries to recover from a strong uppercut delivered by COVID-19

- Share via

He’s still 22.

As much as Vergil Ortiz Jr. reminds himself of that, he can’t stop wondering about what he’s lost over the last three months.

“In my mind,” he said, “I have a whole lot of what-ifs.”

He’s not alone.

The undefeated welterweight is part of a part of a group of a promising up-and-coming fighters that includes lightweights Teofimo Lopez, Devin Haney and Ryan Garcia, as well as featherweight Shakur Stevenson.

Lopez and Stevenson are 22. Haney and Garcia are 21.

“This was supposed to be everyone’s breakout year for my generation.”

— — Vergil Ortiz Jr., 22, an undefeated welterweight

“This was supposed to be everyone’s breakout year for my generation,” Ortiz said.

The pay-per-view shows and championship fights that Ortiz and his contemporaries envisioned will have to wait, as boxing recovers from a mandatory standing eight-count it was forced to take because of the coronavirus outbreak.

Ortiz will headline the card scheduled for July 24 that will mark boxing’s return to California. He is matched against veteran Samuel Vargas at a spectator-free arena at the Fantasy Springs Resort Casino in Indio.

By now, Ortiz figured he would already have fought once or twice this year and that a bout for a title or a showdown against a big-name opponent would be around the corner. He now acknowledges that economic realities have virtually eliminated the possibility of a high-profile fight for the foreseeable future.

Broadcasts and ticket sales are the primary sources of revenue in the sport. Major fights typically generate seven- or eight-figure gates, but not anymore. Emergency regulations prohibit live audiences, a dynamic that makes it financially unfeasible for a promoter to offer a top fighter the kind of payday he would demand to accept a high-risk assignment. The development is a blow to an industry that was already dealing with the loss of a major sponsor in Tecate, which has shifted its advertising dollars elsewhere.

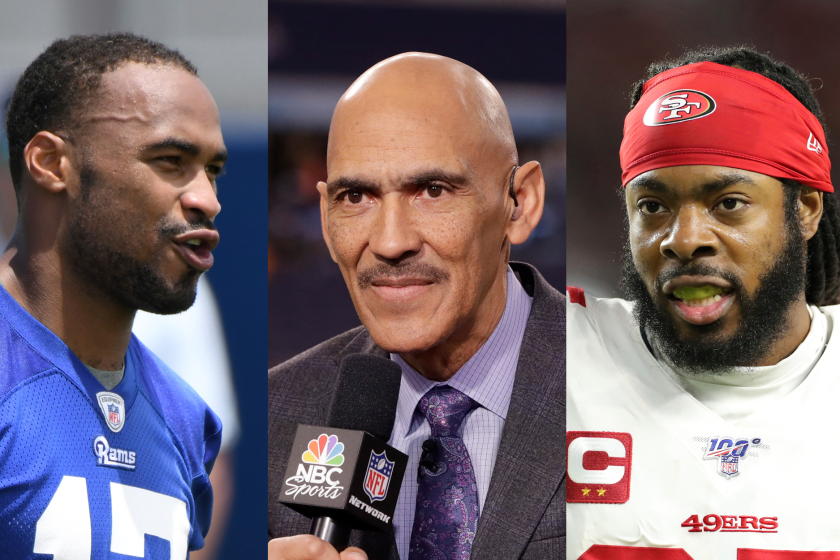

Richard Sherman, Tony Dungy and Robert Woods join The Times’ LZ Granderson and Sam Farmer to discuss social justice, racism and the NFL.

The situation could sideline the sport’s No. 1 attraction, Canelo Alvarez, according to Eric Gomez, the president of Golden Boy Promotions.

“In the beginning of the year, we were talking to Team Canelo about possibly fighting three times this year,” Gomez said. “Now, we’re going to be lucky if we get one fight in.”

Golden Boy is exploring a September fight for Alvarez, but Gomez warned, “As of right now, it would be with no fans. So we’re going through the process of presenting a plan to him.”

What’s almost certain is that his opponent won’t be the popular Gennady Golovkin.

Alvarez’s initial encounter against Golovkin, in 2017, generated a live gate of $27.1 million. The figure for the rematch a year later was $24.5 million.

“If you look at the history of Canelo’s fights, the biggest gates he’s done was with Golovkin,” Gomez said. “It wouldn’t make sense for us to do it with no fans.”

Asked what kind of opponent Golden Boy could afford, Gomez chuckled.

“Whoever’s available,” he said.

Alvarez draws well regardless of whom he fights, and he could decide even a low-risk opponent isn’t worth his time if he can’t bolster his pay with ticket sales. An Alvarez fight, Gomez said, is “not just a fight. It’s a huge event.”

Ortiz appears less affected by the crowd ban.

Vargas is the same fighter he was supposed to face on March 28 in a fight that was canceled because of the pandemic. Shows that size are more dependent on broadcasting rights fees than ticket sales because they draw only a few thousand fans. However, Ortiz could feel the impact of the coronavirus if he emerges with an expected victory.

The three recognized world champions at his weight class are Manny Pacquiao, Terence Crawford and Errol Spence. As it was, a fight between Ortiz and any one of them was a longshot because they are with other promotional outfits. The absence of a gate downshifts the possibility from remote to non-existent.

There are several other big-name welterweights Ortiz could take on to bolster his profile, including Danny Garcia, Shawn Porter and Adrien Broner. However, Ortiz will have trouble convincing any of them to share a ring with him. With all 15 of his victories coming by knockout, Ortiz has a particularly punishing style. A well-known fighter will almost certainly demand a premium to fight him, something unlikely to materialize in this economic climate.

“I’m not going to cry over that,” Gomez said. “There’s people that are dying out there. So many people have lost their lives.”

Gomez is confident this time can be used wisely by being smart about matching Ortiz.

“You want to get them in a position to fight for a world title, but you want to be able to get them in position and get them the experience that he’s going to need to win the title,” Gomez said.

By speaking up about Juneteenth, Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw underscored the importance of white athletes taking a stand that Black lives matter.

Vargas, 31, is an example. He has 38 career fights, including four against former world champions.

Not every prospect is satisfied with simply gaining experience, however. Ryan Garcia is less polished than Ortiz but is considerably more popular. His model good looks have helped amass 4.5 million followers on Instagram.

Before the sport’s hiatus, Garcia was anticipating a lucrative showdown against former champion Jorge Linares. With that fight on hold, Golden Boy offered Garcia a July 4 tune-up. Garcia considered the financial terms insufficient and declined.

Matchmaking isn’t the only obstacle promoters are encountering. There are also additional expenses.

Promoters are financially responsible for coronavirus-related safety measures in place, according to emergency regulations for combat sports that were approved last week by the California State Athletic Commission. That includes everything from plexiglass barriers to protect judges at ringside to COVID-19 testing and extended lodging for everyone involved in the show, from the fighters to members of the broadcast production team. A document authored by the CSAC estimated the promoters will have to spend an average of $36,860 per show to implement the rules.

But, Gomez said, “We have to get back to some sort of normalcy, so the fighters can fight. A lot of these fighters don’t have a job. They make their money fight to fight. It’s not just about us.”

Compared to other parts of the country, California has a healthy appetite for boxing, evidenced by how everything from major cards at Staples Center to small shows at the Avalon nightclub in Hollywood can attract crowds. Asked if he thought the state could maintain its place as the sport’s spiritual center, CSAC executive director Andy Foster pointed to another of its advantages.

“California does have a large studio environment as well,” Foster said. “There’s a lot of production personnel and facilities in Southern California.”

Despite spikes of COIVD-19 cases, sports leagues are stubbornly moving forward with resuming or starting their seasons, writes columnist Bill Plaschke.

The CSAC is nonetheless bracing itself for a downturn. The state expected to host 160 boxing and mixed-martial arts shows in 2020 and 2021. Now, it is anticipating 30. That will cost the CSAC an estimated $2.75 million it would normally collect from broadcasting fees and ticket sales.

The challenges are such that Gomez defended rival promoter Top Rank against criticism for a series of uneven shows in Las Vegas this month.

“As a promoter, nobody wants to do boring fights,” Gomez said. “In order to make a good fight, the first thing you need is luck.

“I don’t care who you talk to, I don’t care what they say, you can look on paper and it can seem like a boring fight and all of a sudden, it’s a great fight. You never know what you’re going to get. And right now, we as promoters, we’re handicapped.”

And they might stay that way for a while. The CSAC wrote that it expects emergency regulations to be in effect for about a year.

As a business, boxing can be ruthlessly pragmatic, which is why its ethics are often questioned. In this particular case, that mind-set can serve the sport well.

“As soon as you accept that it’s a new world and you have to take precautions, you have to be safe, you have to wear your face mask, social distance, all that stuff, the better off you’re going to be,” Gomez said. “The people that don’t want to accept it, the people that want to go back to the way it was, are going to have a hard time with it. It goes for boxing, too. The fighters that accept it, that there’s a new normal, the better off they’re going to be.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.